📅 Date Published

April 28, 2024

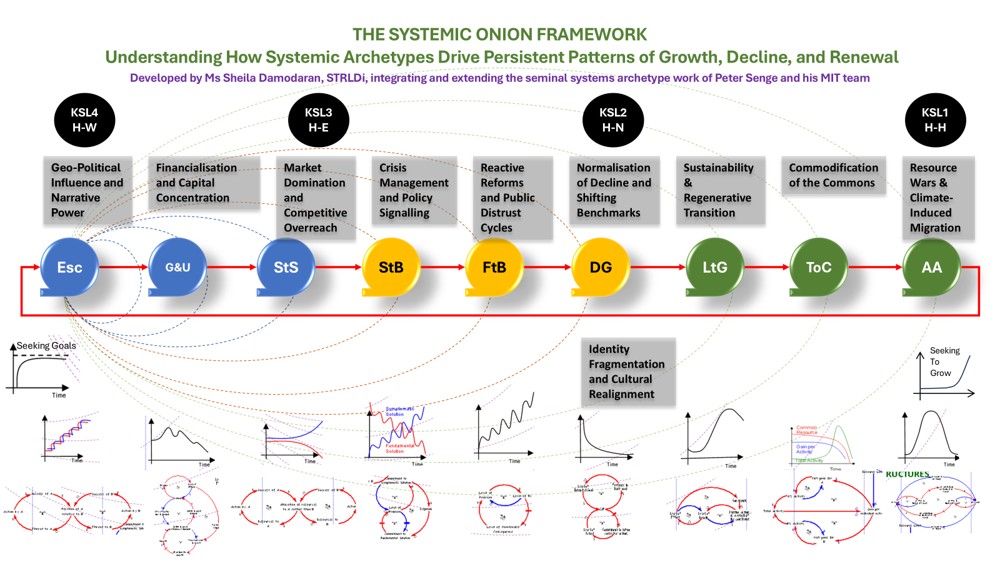

Main visual: Flowchart-style illustration showing system traps (feedback loops and delays).

(Ensure this visual is saved or embedded when republishing.)

📖 Index – Part 2: The Pathway Forward

Introduction: What We Covered in Part 1

Quick recap and transition into actionable areas for reform

Why Manufacturing and Agriculture Struggle to Grow

The education-sector mismatch and weak value chain integration

The Family Structure and the STEM Gap

How early cognitive development affects long-term workforce capacity

The Entrepreneurial Trap

Why relying solely on entrepreneurship won’t solve systemic unemployment

Building a National Economic Coordination Engine

The missing institution to align government, industry, and communities for transformation

Sector Strategy: Plugging into Regional Demand

Opportunities to scale manufacturing across SADC and beyond

Closing Reflections and Next Steps

Call to action for government, private sector, and citizen co-creators

Opening Paragraph: Digging Deeper into the System

From Structural Insight to Societal Design

In Part 1, we uncovered how Botswana’s unemployment crisis is not simply an economic issue—it is the result of a system that was never structurally designed to absorb all its people into productive work. We explored how this system creates persistent gaps between education, enterprise, and employment, and why sectors like agriculture and manufacturing—though full of potential—have remained underutilized.

Part 2 continues this journey with a deeper look into the social systems and feedback loops that silently reinforce the status quo. It expands the lens to include:

- The education pipeline and its disconnect from labour market realities

- The overlooked influence of family structure in shaping national STEM capacity

- The limits of entrepreneurship as a one-size-fits-all solution

- And the capabilities mindset needed to rebuild a labour market that generates meaningful, inclusive employment

Together, these insights challenge us to move from temporary fixes to structural redesign—not just of the economy, but of the cultural, educational, and institutional systems that make it work.

Section 1: The Labour Absorption Gap

At the heart of Botswana’s unemployment crisis lies a structural gap: the economy is not designed to absorb its own people into productive, formal employment.

Every year, thousands of young people complete their education and enter the labour market. This is not a surprise—it is a predictable outcome of birth and schooling patterns observed 15 to 20 years earlier. Yet, despite this foresight, there is no built-in mechanism to ensure the economy expands in ways that absorb this growing workforce.

“We know when children are born, but we do not prepare the economy to receive them as workers.”

Instead of proactive planning, job creation is often treated as a reactive policy issue, tackled after economic pressures surface. The result is a growing backlog of underutilized talent, particularly among the youth, and rising social and economic strain.

What makes this more serious is that the labour force continues to grow, while the sectors best positioned to absorb labour—such as agriculture, manufacturing, and STEM-related services—remain either underdeveloped or stagnant. The informal sector temporarily absorbs some of this pressure, but it lacks the structure, protections, and scalability needed for long-term national prosperity.

This labour absorption gap is not a failure of individuals—it is a failure of system design. And until it is addressed at the structural level, any attempt to reduce unemployment will only scratch the surface.

Section 2: Skills Mismatch

LIMITS TO GROWTH OF MANUFACTURING & AGRICULTURE ECONOMIC SECTORS IN BOTSWANA

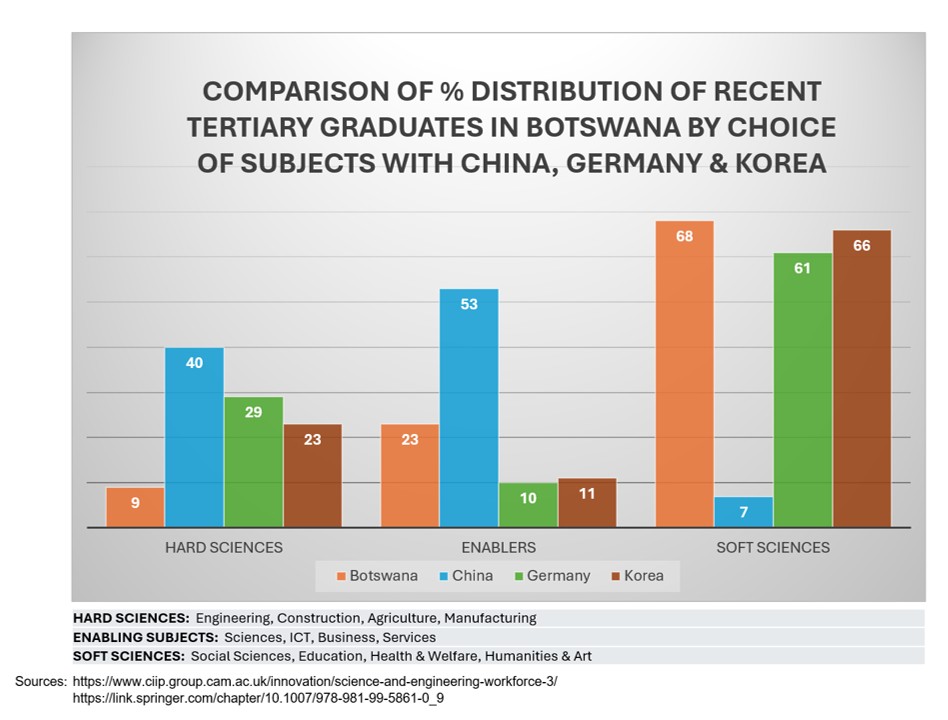

At the heart of Botswana’s labour market stagnation lies a persistent misalignment between education outcomes and economic sector needs. Despite steady investments in schooling and training, the pipeline from education to employment—especially in high-absorption sectors like agriculture and manufacturing—remains weak.

A System Designed Without Absorptive Capacity

A systems diagnosis reveals that the current configuration of the education system is structurally geared toward soft sciences—fields such as business studies, humanities, social sciences, and education. While these disciplines are valuable to a functioning society, they do not offer the absorptive scale or productivity gains necessary for industrial growth, economic self-sufficiency, or widespread job creation.

As a result, Botswana’s two most labour-intensive sectors—agriculture and manufacturing—remain underdeveloped, contributing a fraction of what the retail and service sectors do. In some cases, they generate as little as one-fiftieth the revenue of the retail sector.

“An economy that avoids production cannot scale employment. It can only circulate consumption.”

What’s Limiting the Shift?

Despite widespread awareness of the need for STEM-related skills, the transition has been slow. Several interlocking factors explain this:

- Educational history and social perception: STEM disciplines are widely perceived as harder, less accessible, and more intimidating—especially in communities with weak early exposure to math and science.

- Limited technical infrastructure: Vocational and technical training institutions remain under-resourced and under-prioritized.

- Career pipeline uncertainties: Even employers in STEM-related industries often struggle to offer long-term pathways for growth or specialization, discouraging students from entering or staying in the field.

- Policy fragmentation: Education policy, economic planning, and labour market development operate in silos, with limited coordination or shared goals.

The Resulting Skill Mismatch

Only 10% of graduates complete qualifications in science or applied science fields. Of this:

- About 6% are in engineering

- About 7% in the hard sciences

- Less than 1% have training relevant to manufacturing

These proportions reflect tertiary-educated populations, meaning even fewer within the broader labour force possess the hard science and technical skills required for scaling production and industrial competitiveness.

Meanwhile, fields that don’t require economies of scale—such as nursing, teaching, or civil service—continue to grow, because they are state-funded and do not face direct market pressure to turn a profit.

This creates a self-justifying narrative: “We are better off pursuing white-collar jobs, where the money and security lie,” even though these sectors offer limited employment elasticity.

Where STEM Skills Still Matter

The paradox is that even in non-STEM jobs, transferable STEM skills—critical thinking, problem-solving, data literacy—are becoming more valuable across all sectors. Yet, Botswana’s slow pivot to STEM is not just about curriculum—it reflects a deep structural dependency on government employment and a lack of market-driven pathways for applied science fields.

What’s Needed

To unblock this feedback loop, Botswana must:

- Rebalance tertiary education priorities, with aggressive incentives for STEM fields

- Strengthen early exposure to math, science, and technical learning in primary and secondary schools

- Invest in technical colleges and vocational training centres with modern equipment, qualified instructors, and employer partnerships

- Create visible career ladders in agriculture, manufacturing, and industrial trades, backed by both private investment and public policy

- Change the story: Productivity-driven work—whether on farms, in factories, or in labs—must be reframed as noble, necessary, and rewarding.

This is not only a matter of jobs. It’s about redesigning the architecture of Botswana’s future—where learning meets labour, and effort meets opportunity.

Section 3: The Role of the Household

Botswana’s persistent unemployment is not only economic or educational in origin—it is deeply social and familial. A closer look reveals that the very foundations of how children are raised, mentored, and prepared for the world of work carry profound implications for the country’s STEM capacity, labour readiness, and economic diversification.

Cognitive Development Starts at Home

By 2022, 84% of births in Botswana were ex-nuptial, with projections pointing to near-universal levels by 2030. This marks a dramatic restructuring of family life, where female-headed households—often without resident male support—carry the weight of child-rearing, often under significant economic strain. Many of these women are themselves unemployed or dependent on informal networks or social grants, which limits their ability to provide sustained cognitive enrichment for children.

The long-term implication? A large portion of Botswana’s youth develops strong capacities in social, emotional, and communicative skills, but lags behind in STEM disciplines—especially in mathematics, engineering, and physical sciences.

Research and behavioural patterns show that male mentorship—particularly through father figures—plays a critical role in fostering abstract reasoning, spatial cognition, and systems thinking, all of which are foundational to technical mastery in STEM fields.

“Botswana’s children are not failing STEM. STEM is failing to meet them where they are—and failing to reach the homes where foundational development should begin.”

Downstream Effects on National Sectors

This learning gap doesn’t stop at school. It extends into the economy. Sectors like agriculture and manufacturing, which rely on technical, spatial, and mechanical reasoning, continue to suffer from a lack of skilled labour. Despite their potential to absorb large segments of the unemployed population, these sectors remain underdeveloped and uncompetitive—not because of funding alone, but because of a shortage in the foundational STEM capabilities that underpin profitable, scalable operations.

Without a deliberate strategy to rebuild the cognitive and emotional ecosystem in households, Botswana risks reinforcing the very structural traps that sustain long-term unemployment.

Why the Family System Matters to Economic Planning

This is not just a moral or cultural concern—it is a strategic one.

Economic growth, industrial competitiveness, and technological innovation begin with brain development, mentorship, and multi-parental support in the early years. Without that, later reforms in education, vocational training, or entrepreneurship will not yield the intended systemic shift.

This family structure imbalance has also supported the expansion of employment in white-collar and social service roles (e.g. healthcare, teaching, government), which tend to be more forgiving of emotional labour gaps but do not require technical scale or global competitiveness.

Meanwhile, more masculine-coded, production-driven industries, which demand precision, long-term focus, and mechanical thinking, are either avoided or underutilised—widening the skills gap and deepening economic fragility.

The role of intact families in economic transformation is often misunderstood as moral or cultural. It is neither.

As this study shows, productive economies—particularly those requiring STEM depth, manufacturing precision, and systems competence—depend on long-horizon learning and apprenticeship. Those capacities are not transmitted episodically through short-term training or policy cycles; they are compounded slowly through stable relational environments. Where families are intact, children inherit patience, delayed reward, and confidence in continuity. Where families are structurally fragile, learning horizons shorten and skill accumulation leaks. A companion analysis (“Violence Starts in Silence”) examines how prolonged unemployment, migration, and economic exclusion thin family stability itself—creating a reinforcing loop in which weakened families further undermine the very skill base productive economies require. Economic strategy, therefore, cannot be separated from the conditions that allow families to form, stabilise, and transmit belief forward.

Restoring Balance: Fatherhood, Identity & Resilience

To reverse these trends, Botswana must design holistic interventions that reframe fatherhood—not merely as financial contribution—but as an essential cognitive and emotional pillar in national development.

Key strategies include:

- Shifting public policy from reactive punishment of gender-based violence to proactive support for healthy family formation and co-parenting

- Embedding father-positive identity work in schools and communities: teaching boys to resolve conflict, lead with emotional intelligence, and value interdependence

- Empowering girls and young women to choose family partnerships out of mutual respect, not economic survival

- Developing curricula and parenting models that recognise the neurocognitive link between household stability and STEM success

“When we restore balance at home, we lay the cognitive and emotional groundwork for economic resilience in the nation.”

Build A Nation Ready to Compete Starts at Home: Building Botswana’s Production-Ready Future

Reclaim the household as the first economy—the place where work ethic, discipline, resilience, and self-sufficiency are formed. Botswana’s pathway to enduring prosperity lies not in aid or consumption, but in cultivating a tech-smart, production-ready workforce—an engine of national transformation that can power the next generation of agriculture, manufacturing, and export-oriented enterprises.

We must train not just for employment, but for global competitiveness. This means equipping citizens with technical competence, entrepreneurial mindset, and systems thinking—alongside a national culture that values efficiency, learning, and precision. It is no longer enough to aim for participation in the economy. We must become builders of it.

Industrial growth must be anchored in people-powered productivity. Let us shift from a model of aid-dependent employment to one of export-led livelihoods—grounded in long-term strategy, backed by modern infrastructure, and evaluated by how much value we create and retain at home.

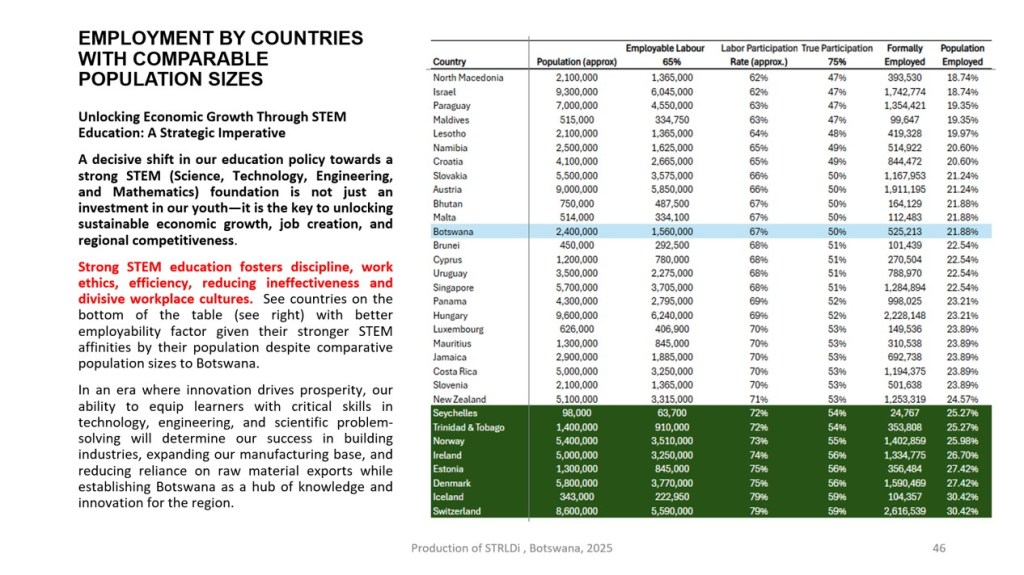

Small Nation, Global Standards

Botswana’s size is not a constraint. It is our strategic advantage. We can move faster, integrate lessons quicker, and manage costs more smartly than our global competitors. With the right tools and mindset, Botswana can outperform much larger economies by focusing on high-efficiency production and smart value-chain integration.

If we focus our energy on cultivating a labour force designed for precision, discipline, and innovation, there is no reason Botswana cannot become a sought-after hub—first in SADC, then the continent, and globally.

This is our opportunity to lead—not just because we must, but because we can.

Summary of Implications

- Unemployment is not only about a lack of jobs, but about a shortage of readiness—cognitively, emotionally, and structurally

- The STEM education gap begins in early childhood, especially in father-absent homes

- Key sectors cannot expand without a technically skilled labour force

- White-collar sector growth is not absorbing enough workers to sustain economic growth

- Economic dependence models (on grants, remittances, and retail) are crowding out productivity models

- To break this cycle, Botswana must invest in:

- Foundational household systems

- STEM pathways starting from early childhood

- Gender-balanced parenting

- Sector strategies tied to human development

Section 4: Feedback Loops in Action

When seen through a systems lens, Botswana’s unemployment crisis is not a series of disconnected challenges—it is a tightly woven pattern of reinforcing feedback loops.

Each of the structural issues explored so far—labour absorption gaps, skills mismatches, and household instability—feeds into and amplifies the others.

“Low productivity leads to low wages. Low wages weaken households. Weakened households undermine learning. Poor learning reinforces low productivity.”

This creates a self-reinforcing cycle, where the effects of one issue become the causes of another:

At the national level, these loops trap Botswana in a cycle where investments yield minimal systemic return, because they do not address the structures that are recreating the problem.

What appears to be a policy gap or implementation failure is, in fact, the behaviour of a system designed in such a way that it continually reinforces its own stagnation.

Until these feedback loops are disrupted, interventions will continue to treat symptoms rather than shift outcomes. Short-term successes will be absorbed into long-term patterns—and unemployment will persist.

“In systems thinking, the challenge is not to find someone to blame—it’s to find the loop you need to work at to reverse its effects – from its negative to its positive form.”

Section 5: The Entrepreneurial Trap

Why relying solely on entrepreneurship won’t solve systemic unemployment

Botswana, like many emerging economies, has championed entrepreneurship as the primary solution to unemployment. While entrepreneurship is an essential part of a dynamic economy, the push for everyone to become a “job creator” overlooks deeper structural realities.

Our study finds that entrepreneurship alone cannot solve persistent unemployment for three key reasons:

Structural Barriers Remain:

Many aspiring entrepreneurs face systemic constraints—such as limited access to startup capital, weak value chains, low local demand, and inadequate market infrastructure. These barriers prevent even the most enterprising individuals from succeeding at scale.

The Labor Market Needs Rebuilding:

Before entrepreneurship can flourish equitably, Botswana must rebuild its labor markets and strengthen its enterprise ecosystem. That means creating a broader base of functional, mid-sized firms that can employ others, mentor smaller startups, and stimulate demand.

Risk Is Not Equally Distributed:

The entrepreneurship narrative often shifts risk onto individuals—especially the youth—without reforming the broader systems that enable business survival. In effect, many young people are encouraged to pursue entrepreneurship out of necessity, not opportunity, which only deepens economic insecurity.

Instead of promoting entrepreneurship as a standalone solution, the study recommends investing in sectors that can:

- Absorb large numbers of skilled and unskilled workers;

- Offer stable jobs and structured career pathways;

- Foster local supplier networks where entrepreneurship can take root with institutional support.

- Only 10% of the population is entrepreneurs.

- Of these, 70% are survivalist / opportunitistic entrepreneurs, with no long-term plan to employ workers, while only 30% are growth-oriented.

- This highlights why entrepreneurship—on its own—cannot carry the weight of systemic job creation.

When entrepreneurship is nested within a productive, coordinated value-chained economy—rather than seen as a replacement for it—it becomes a powerful tool for resilience and innovation.

Section 6: Coordinating the Economy for Systemic Transformation

Despite years of targeted reforms and investment initiatives, Botswana’s economy continues to fall short of its employment, productivity, and diversification targets. Our study shows that this is not due to a lack of will or capital, but to the absence of systemic coordination, misaligned leverage points, and the failure to embed long-term competitiveness in foundational sectors.

1. The Need for a National Economic Coordination Engine

Botswana’s current transformation framework is led through ministry silos, isolated reform units, and project teams. While well-intentioned, this approach lacks the capacity to synchronize cross-sector planning, create enduring institutional memory, and drive multi-year industrial development.

A central economic coordination engine is urgently needed—one that:

- Connects MITI, BITC, private producers, educational institutions, and investor ecosystems

- Sequences industrial development (upstream → midstream → downstream)

- Sequencing value-chain development across time and geography

- Tracks workforce readiness and adapts education-to-labour pipelines in real time

- Functions outside short-term political and project cycles

“We cannot build an economy through siloed enthusiasm. It needs a brain that sees the whole body and coordinates its movement.”

This is the missing engine—a cross-sectoral national body that can drive, steer, and synchronise the country’s economic transition.

Such a structure should:

- Be empowered to guide long-term industrial sequencing and regional trade competitiveness

- Monitor workforce readiness and gaps in real time

- Anchor its work in both national development and systems thinking

- Operate beyond political or project cycles

Without this coordination mechanism, reform will continue to stall and progress will be patchy, fragile, and reversible.

2. Household Systems Are the Hidden Leverage for STEM and Productivity

The study has shown a powerful, overlooked factor: household structure. Over 84% of children today are born outside of formal unions—many into single-parent homes where financial, emotional, and cognitive resources are limited.

This fragmentation hinders:

- Early development in abstract and spatial reasoning (vital for STEM)

- The confidence and discipline required to pursue science-based careers

- Gender-balanced learning environments that support persistence and long-term planning

Only 10% of graduates are trained in applied sciences or engineering. This is not just an education problem—it’s a social systems issue, stemming from the ground-up. Without deliberate intervention, our factories and farms will continue to struggle—not from lack of capital, but from a weak pipeline of technically competent talent.

3. Build to Sustain a Strong, Self-Resilient Economy

Botswana is uniquely positioned to expand its manufacturing base by tapping into unmet regional demand—especially within the SADC region, where intra-African trade remains underdeveloped.

Rather than continuing to depend on extractive industries or retail imports, Botswana can reposition itself as a regional producer of essential goods. The key is to plug into value chain gaps and high-demand products that are currently being sourced from outside the continent.

Priority Sectors with Regional Demand Potential:

🏗️ Agro-Processing and Food Manufacturing

- Canned/frozen produce, milled grains, dairy, meat products, juices, sauces, animal feed

- 📌 Why it matters: Most are imported into SADC from South Africa, Brazil, and Europe, despite regional raw produce being available.

🧼 Essential Consumer Goods

- Soap, toothpaste, sanitary pads, school supplies

- 📌 Why it matters: Basic goods still largely imported—Botswana can become a lower-cost, nearer alternative.

🧵 Textiles and Garments

- School uniforms, workwear, basic garments

- 📌 Why it matters: Regional markets (Zimbabwe, DRC) import from Asia—Botswana can serve SADC with faster delivery and lower shipping costs.

🧱 Construction Materials

- Roof sheets, cement, steel frames, precast items

- 📌 Why it matters: Construction boom in SADC needs affordable, local materials—Botswana is well-positioned geographically.

💊 Pharmaceuticals and Medical Consumables

- Generic drugs, gloves, bandages, veterinary medicines

- 📌 Why it matters: Many countries import 70–90% of these—Botswana can build a clean, trusted base for production.

⚙️ Automotive and Machinery Assembly

- Farm tools, vehicle spares, irrigation kits

- 📌 Why it matters: Regional farmers depend on imports—Botswana can be a reliable assembly and service base.

🔌 Packaging Materials

- Plastic, cardboard, labels, paper-based packaging

- 📌 Why it matters: Every regional producer needs packaging—Botswana can become a packaging hub.

✅ Implementation Strategy:

- Locate industrial clusters along trade corridors (e.g., Lobatse, Francistown, Palapye)

- Leverage SACU and SADC agreements for near-captive regional markets

- Attract anchor firms with procurement incentives and public-private partnerships

- Align skills development with product-specific industrial goals

- Use AfCFTA to eventually scale toward continental market leadership

“We are not short on vision. We are short on synchronised execution. A well-planned manufacturing base will create the jobs our economy desperately needs.”

4. Building an Industrial Base Requires More than Capital Injection

Historically, Botswana’s agriculture and manufacturing sectors have consistently failed to generate sustained profits or absorb labour. This is not for lack of funding, but because:

- Productivity remains low,

- Input costs remain high,

- Workforce skills are mismatched,

- And sectors operate in silos with no connected value chains.

We cannot build these sectors organically. They must be engineered deliberately, with intentional sequencing, backward-forward linkages, and a consistent domestic and regional market focus.

5. Embed Job Creation into Economic Expansion

Economic growth alone will not solve unemployment. Botswana must intentionally embed employment outcomes into its development plans.

That means:

- Prioritising labour-absorbing sectors like agriculture, local manufacturing, and service supply chains

- Moving from extractive and retail dependency to production-based economies

- Creating incentives for firms to adopt scalable, competitive, and job-generating models

- Redesigning vocational and tertiary education to serve the production economy—not just the government or service economy

“True transformation happens when economic activity creates income, dignity, and participation at scale—not just profit.”

Key Quote (pullout):

“Unless employment is built into the structure of the economy, the workforce will keep outgrowing opportunities—and the cycle will continue.”

Yes, we do have content that aligns with “Closing Reflections and Next Steps” from the final sections of Part 2. Below is a refined version that fits the tone and purpose of a call to action for government, private sector, and citizen co-creators:

Section 7: Closing Reflections and Next Steps

A Call to Action for Government, Private Sector, and Citizen Co-Creators

The study reveals that persistent unemployment in Botswana is not just an outcome of economic underperformance—it is a structural reality reinforced by deep, interconnected systems: weak sectoral coordination, a misaligned education pipeline, fragmented family structures, and economic dependence on a narrow base of extractive and retail activity.

To reduce the effects of this negative cycle and harness its positive effects instead, we must stop viewing unemployment as a standalone problem and begin to see it as a system to be redesigned. This means:

🔹 For Government:

- Create a National Economic Coordination Engine that aligns ministries, industry, educators, and communities.

- Shift from ministry-specific projects to a shared, long-term strategy that strengthens productive value chains.

- Rebuild trust and traction through inclusive planning platforms that invite cross-sector leadership and long-range thinking.

🔹 For the Private Sector:

- Recognize your role not just as investors, but as co-creators of national productivity and employment ecosystems.

- Invest in skills development and vocational pipelines aligned with the needs of agro-processing, manufacturing, and strategic services.

- Partner in building regional supply chains—with local procurement strategies and scalable models that anchor growth.

🔹 For Citizens and Households:

- Reclaim the household as the first economy—the place where work ethic, discipline, resilience, and self-sufficiency are formed.

- Advocate for STEM literacy and family balance, not just as personal goals, but as national priorities.

- Reimagine employment as a shared, societal outcome—not just the responsibility of the state or market.

“Botswana has what it takes to shift from economic fragility to generative resilience. But the shift won’t come from another round of spending—it will come from a new commitment to learning, alignment, and long-range systems design.”

Let us not lose this moment. Let us design together—across sectors, institutions, and generations. This study is not the final word; it is the invitation.

Conclusion: From Insight to Action

This study offers not just analysis, but a roadmap for redesign. Through systems thinking, we can move beyond short-term fixes and begin building a structure where every Batswana has a fair shot at meaningful work.

Botswana is not short of effort, intention, or resources. What it lacks is a system that can absorb, develop, and circulate human potential at scale. This study has shown that unemployment is not a policy failure—it is a structural consequence of how we’ve designed, connected, and reinforced our core institutions.

But systems can be redesigned.

Through systems thinking, we can now see the loops, gaps, and leverage points clearly. We know where to shift. The choice ahead is whether we will continue to operate on inherited assumptions—or rise to redesign the economy for inclusion, productivity, and regeneration.

“The future will not be built by accident. It must be structured.”