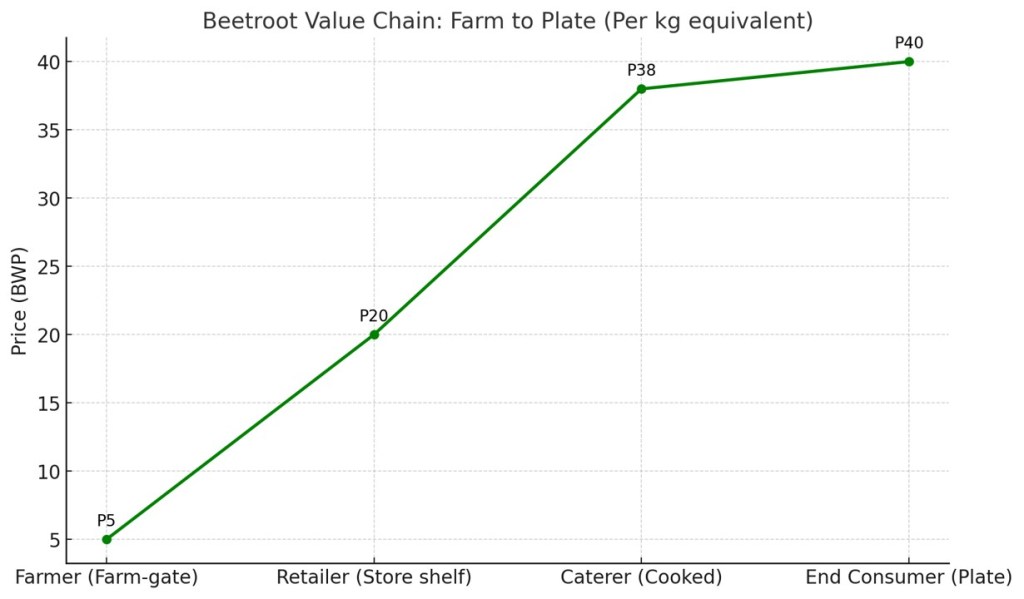

From P5 beetroot to a P40 plate—why profits “move but don’t grow” without a coordination spine.

When the Butterfly Sneezes: The Unseen Players in Botswana’s Food System

🌾 Farmer’s Voice — A Passion of Hope

“Once we finish planting, the imports come in. Prices drop to P3 a kilo.

We can’t dodge the same old crops — cabbage, tomato, butternut — and tunnels cost over P90 000.

Try niche crops, they say, but even herbs and radish sell for cents.

Retailers buy my produce at P3 and sell at P4–P20.

When will we ever break even?”

— Farmer, Botswana (2025)Inside this lament is not anger but a map of a missing system.

He is describing an uncoordinated market where imports collide with local harvests, costs outrun prices, and data never travels between field, retailer, and policy desk.

It is the voice of someone working hard within a structure that works against him — what he calls “a passion of hope.”

That hope deserves a system strong enough to hold it.

The thread flares up with emotion. Dozens of voices add their experiences — the weather, the labour costs, the diesel bills, the price of packaging. Some call for subsidies, others for stricter import bans. Others say forget the local market. Go the way of exports. This conversation happens repeatedly in farmer groups. It occurs month after month. Every time a price thread catches fire, the discussion resurfaces.

And yet, hidden inside those messages is a larger pattern — one that rarely gets named. Farmers argue about prices. However, the real leverage lies elsewhere. It is in the soil beneath them. It is in the productivity of the labour beside them. It is also in the structure of the state above them.

It is easy to think that solving the farmer’s problem begins with the farmer. But economics tells us otherwise: the points of highest leverage in a system are usually the least obvious.

Our farmers’ frustration is real. However, the forces that shape it are mostly invisible. This encompasses the movement of data between ministries. It also involves the management of soil biology, the training of labour, and the sustenance of coordination. The pain of one player in the system often begins in the silence of another.

This article quantifies each layer, shows the ripple when farm-gate rises, and identifies the leverage points that actually grow profit.

Three Learning from This Study

These three learning define the real work ahead. It is the work that, if we take care of it, will make these circular farmer–retailer–caterer conversations unnecessary. They form the foundation for the next phase of Botswana’s agricultural and economic development.

1. Reduce Production Costs to Global Competitive Levels

Our first task is to bring our unit production costs down from P5.50–P6.20 to around P3.00/kg, matching China’s cost base.

That P2.00 difference is significant. It represents a full P2 profit margin per kilogram of beetroot (and comparable crops). This margin currently leaks away in inefficiency.

We can only achieve this through regenerative practices, precise data coordination, and investment in mechanisation where it matters.

Outcome: Lower costs mean higher margins for farmers without raising consumer prices — the hallmark of a mature, competitive system.

2. Confront Productivity Honestly and Set National Targets for Labour

Our workers are not underpaid — they are undirected.

The value of their pay is being eroded not by exploitation, but by inflation born from low productivity.

We must stop pretending otherwise. We should begin publishing comparative productivity data. This data shows how Botswana’s average agricultural worker performs in kilograms per hour against peers in China, Malaysia, and India.

Then, set measurable targets:

- Increase output per labour-hour by 20% within 3 years,

- Match Malaysia’s productivity by year 7,

- Halve the labour cost per kilogram by year 10.

Outcome: Higher real wages are built on productivity, not inflation. The workforce knows exactly what “competing globally” means in numbers, not slogans.

3. Rebuild the Country’s STEM Foundations Early

Here’s a clear and grounded explanation that moves step by step from STEM → Efficiency → Productivity → Prosperity.

🌱 a. STEM builds understanding — not just knowledge

STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics) teaches people how things work — not just what to do.

That shift in understanding is crucial.

- Science helps workers grasp cause and effect (e.g., soil chemistry, pest cycles, plant physiology).

- Technology provides the tools to measure, automate, and communicate those effects.

- Engineering applies design thinking — how to improve irrigation, logistics, or packaging systems.

- Mathematics enables measurement, optimization, and decision-making (costs, yields, probabilities, scaling).

Together, these disciplines cultivate systemic awareness — people start seeing connections, feedback, and waste.

And once you see inefficiency, you can eliminate it.

🔍 Efficiency begins the moment a person can measure and model reality accurately.

⚙️ b. Efficiency is the visible expression of STEM in action

Efficiency simply means achieving more output for the same or fewer inputs — time, money, energy, or labour.

STEM translates into efficiency in concrete ways:

| STEM Area | Practical Impact on Efficiency | Example in Agriculture |

|---|---|---|

| Science | Understanding soil, plant, and climate interactions | Farmers apply the right nutrients at the right time instead of over-fertilising. |

| Technology | Mechanisation, sensors, digital tools | Moisture sensors save 30% of water and improve yield by 10%. |

| Engineering | Better designs, less friction | Efficient irrigation pumps reduce energy use by 20%. |

| Mathematics | Tracking costs, yields, and trends | Farmers identify unprofitable crops before planting. |

🌾 Efficiency isn’t about working harder — it’s about working with reality instead of against it.

📈 c. Productivity is efficiency multiplied by scale

When efficiency becomes consistent and repeatable across many workers or farms, it turns into productivity.

- Efficiency is doing things right.

- Productivity is doing the right things, consistently, across the system.

STEM allows workers to perform better individually. It also helps them coordinate through shared data. They use standardised measurements and continuous feedback.

That coordination is what lets a country like China keep unit labour costs low even when wages rise. Every worker is plugged into an information-rich system. This system amplifies output.

🚀 Efficiency makes individuals productive. Coordination makes nations productive.

💰 d. Productivity creates wealth — sustainably

When workers produce more per hour:

- Wages can rise without raising prices (because output per worker increases).

- Borrowing costs drop (because the economy produces more value per unit of debt).

- Inflation falls (because supply keeps pace with demand).

- The nation grows without subsidies.

That’s why improving STEM education and data coordination in agriculture isn’t an “education policy” — it’s a macroeconomic strategy.

It turns a P5.50/kg farm cost into P3.50/kg not through subsidy, but through mastery.

It converts labour from a cost line into a competitive advantage.

🌍 STEM turns energy into knowledge, knowledge into efficiency, and efficiency into national resilience.

In short

| Stage | Question | Answer |

|---|---|---|

| STEM | How do we understand the system? | Through science, data, and reasoning. |

| Efficiency | How do we reduce waste? | By measuring, predicting, and designing better. |

| Productivity | How do we grow sustainably? | By scaling efficiency across people and systems. |

By the time a child reaches tertiary education, it is too late to correct what was never built.

The state must raise the mathematical and scientific literacy of its entire school population, not just the top students.

Our national benchmark must focus on improving Botswana’s average school grades in maths and science. We aim to match the global leaders — Germany, Japan, China, India, and Singapore.

This shift will not just improve education outcomes. It will reset the country’s entire productivity curve. This change will influence how farmers measure yields. It will affect how engineers design systems. Additionally, it will shape how policymakers use data.

Outcome: A generation equipped not only to work harder, but also to think structurally. This creates the muscle memory that drives nations forward.

In summary

1️⃣ Lower costs through coordination and regenerative discipline.

2️⃣ Lift productivity through data transparency and measurable labour goals.

3️⃣ Rebuild national STEM capacity from the classroom upward.

These three actions will work together. They will reduce the noise and emotion of our current debates. Frustration will be replaced with focus. Short-term fixes will be replaced with long-term learning.

Bridging Forward

These three learning give us a compass.

They show where the real work lies. It is not in louder debates over prices or subsidies. It is in building structural strength where it has quietly eroded: cost efficiency, productivity, and foundational education.

The rest of this article explores the data and reasoning that bring these points to life.

It follows a single, ordinary beetroot as it travels from soil to plate. It traces how profit behaves and where it leaks. The journey also examines what happens when we add coordination, regeneration, and STEM capacity back into the system.

From the farmer’s field to the nation’s policy tables, every section connects a visible frustration to its invisible cause.

Together, they reveal why Botswana’s horticulture will only mature when learning, labour, and leadership align.

Table of Contents

When the Butterfly Sneezes – The unseen players in Botswana’s food system

Part A – The Ripple Effect: From the Farmer’s P 5 Beetroot to the P 40 Plate

2.1 An Economic Observation

2.2 Tracing the True Cost of a Beetroot: From Farm to Plate

a. End Consumer – The Office Meal Plate

b. Caterer – Turning Raw Beetroot into a Side Dish

c. Retailer – The Hidden Middle Costs

d. Farmer – The Starting Point

e. The Complete Chain – Costs per kg of Beetroot

f. What the Data Shows

g. The Systemic Insight

2.3 The Baseline System – When the Farm-Gate Price is P 5/kg

2.4 When the Farmer Raises Price from P 5 to P 8/kg

2.5 Comparative Margins Summary

2.6 Where the Ripples Come From

2.7 Structural Insight – Movement without Prosperity

2.8 Bridge to Part B – Raising Productivity and Coordination

Part B – When the Butterfly Sneezes: The Unseen Players in Botswana’s Food System

3.1 The Quiet Cause Behind the Farmer’s Cry

3.2 Comparative Farming Economics – Conventional, Organic and Regenerative

3.3 Labour Productivity and Cost – Botswana, Malaysia and China

3.4 What Happens When Botswana Combines Regeneration with STEM and NHCS

3.5 The Seven Players – and the Three We Forget

3.6 Closing – When the Butterfly Sneezes

Core Takeaway – Changing how we see ourselves in the system

Part A: The Ripple Effect — From the Farmer’s P 5 Beetroot to the P 40 Plate

1. An economic observation

A kilogram of beetroot may seem like a simple commodity. Yet inside that red root is the entire economy of a nation. Six players each shape one another and are shaped by each other. When the farmer lifts her price by a few pula, it affects retailers and caterers. It impacts consumers and labourers. The state is also influenced by this change.

In a well-coordinated system, those ripples dampen quickly. In a disjointed one, they echo back and forth until everyone feels poorer.

Tracing the True Cost of a Beetroot: From Farm to Plate

Understanding why beetroot sells for P20/kg in retail requires unpacking every layer between soil and spoon. The farmer earns only P4–5/kg.

Contrary to the common assumption that retailers “keep the profit,” the real story is quite different. It involves cost absorption and system inefficiency rather than greed.

a. End Consumer – The Office Meal Plate

- Plate price: ~P40 per meal.

- Beetroot portion: ~100 g cooked (≈150 g raw).

- Plates per kg raw beetroot: 6–7.

- Value of beetroot portion: ~P6–7 per plate.

➡️ Effective consumer cost: ≈P40/kg equivalent of beetroot once it is part of a full plated meal.

Summary:

For the consumer, beetroot is not seen as a costly ingredient. It forms only one side of a balanced plate. Yet at P40/kg equivalent, the same vegetable has multiplied eightfold from the farmer’s original P5/kg sale.

Punchline: Consumers don’t see the strain because they see only the plate, not the chain.

b. Caterer – Turning Raw Beetroot into a Side Dish

- Retail purchase price: ≈P20/kg.

- Cooking shrinkage: ~30 % (1 kg raw → 700 g cooked).

- → Effective ingredient cost: P28–29/kg cooked.

- Additional operating costs:

- Cooking oil, vinegar, spices, gas/power: P4–5/kg.

- Preparation labour (washing, peeling, cooking, cutting): P5–6/kg.

- Delivery/logistics: P2–3/kg.

- Total cost to caterer: ≈P38/kg cooked beetroot.

Summary:

At P38/kg, caterers are already operating near breakeven against a P40/kg recovery from the plate price.

Even a small rise in the farm-gate or retail price erases their profit entirely.

This is why caterers appear “price-sensitive”: they have no slack left in their margin.

Punchline: Caterers run on fumes; tiny upstream increases wipe out margin.

c. Retailer – The Hidden Middle Costs

- Buying price from farmers: P4–5/kg.

- Breakdown of additional costs (per kg of final retail price P20):

- Transport from farm: P2 (≈10 %)

- Cold storage, handling, and spoilage: P3–4 (15–20 %)

- Store rent, energy, staff, packaging, compliance, shrinkage: P6–7 (30–35 %)

- Net profit margin: P3–4 (15–20 %)

➡️ Real retailer profit: ≈P3/kg — not P16.

Summary:

What appears to be a wide gap between the farm and the shelf is mostly overhead.

Retailers operate on thin real profits while shouldering refrigeration, electricity, salaries, and spoilage losses.

If it were easy or profitable for farmers to sell directly, many would have done so long ago. Many would have seen 10-20,000 customers walk through their gates each day.

Retailing is a different business — capital-intensive, compliance-heavy, and risky.

Punchline: The “P15 gap” is mostly overhead and risk, not profit.

d. Farmer – The Starting Point

Typical production costs for small to medium beet farms in Botswana:

| Cost Item | Range (P/kg) |

|---|---|

| Seeds & inputs | 0.80 – 1.20 |

| Fertiliser & soil preparation | 0.80 – 1.00 |

| Irrigation, energy & water | 0.60 – 0.80 |

| Labour | 0.80 – 1.00 |

| Harvesting & packaging | 0.50 – 0.80 |

| Farm overheads | 0.50 – 0.70 |

| Total Cost Range | 3.50 – 5.50 |

Summary:

At a selling price of P4–5/kg, farmers are operating at or below cost depending on yield.

This leaves no room for reinvestment in irrigation, labour, or expansion — keeping farms small and fragile.

Punchline: At P4–5/kg, farmers are at/under cost—no reinvestment cushion.

e. The Complete Chain – Costs per kg of Beetroot

| Layer | Input / Base Cost (P/kg) | Selling Price (P/kg) | Approx. Profit (P/kg) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Farmer | 3.5 – 5.5 | 4 – 5 | ≈ 0–0.5 | Breaks even at best. |

| Retailer | 4 – 5 | 20 | ≈ 3 | Real profit ≈ 15 %; bulk absorbed by overhead. |

| Caterer (cooked) | 20 raw → 38 cooked | 40 (plate equivalent) | ≈ 2 | Extremely tight margin. |

| Consumer | — | 40 | — | Sees only final plate price, not the cumulative chain. |

f. What the Data Shows

Retailers are not “keeping” P16/kg.

Most of that margin evaporates into transport, electricity, staff, and spoilage.

Farmers sell at or below cost.

They absorb biological risk without a financial buffer.

Caterers operate on fumes.

Their entire P40 plate price barely covers cooked beetroot costs once prep and logistics are included.

Consumers perceive stability, not strain.

They see the P40 meal, not the imbalanced structure behind it.

Punchline: Movement without prosperity.

g. The Systemic Insight

Every link is absorbing inefficiency because no national coordination spine connects them.

- Farmers plant without market signals.

- Retailers import unpredictably to fill gaps.

- Caterers pay for inconsistency with higher costs.

- Consumers face quiet inflation hidden inside the meal price.

Without coordination, the entire chain functions like a series of disconnected pumps. Each builds its own pressure. None drives flow.

In short:

The beetroot doesn’t cost too little at the farm or too much on the plate. It costs exactly what an uncoordinated system produces. This includes high effort, low reward, and invisible waste.

2. The Baseline System — When the Farm-Gate Price Is P 5/kg

Assumptions: 1 ha = 40 tons yield. Farmer production cost ≈ P 5/kg.

| Layer | Input Cost (P/kg) | Ops & Handling (P/kg) | Revenue (P/kg) | Profit (P/kg) | Margin (%) | Commentary |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Farmer | 5.00 | — | 5.00 | ≈ 0.00 | 0 % | Sells at cost; no cushion for loss or reinvestment. |

| Retailer | 5.00 | 15.00 (transport + storage + staff + shrink + margin) | 20.00 | 3.00 | 15 % | Margin looks high but includes spoilage risk and unionised labour.* |

| Caterer (cooked) | 20.00 (raw) | 18.00 (cooking shrink + ingredients + labour + delivery) | 38.00 | 2.00 | 5 % | Runs on thin margins; relies on volume. |

| Consumer (plate) | 38.00 (cost/kg cooked beet) | 2.00 (service + profit) | 40.00 | — | — | Pays P 40 for a full meal; beetroot one side dish. |

Observation: Every layer is working, few are thriving. The system produces movement, not prosperity.

Although the spread between farm-gate and retail looks like a P15 margin, only about P3 /kg is actual profit.

*The rest — roughly P12 /kg — is consumed by transport, cold-storage energy, rent, packaging, spoilage, unionised wages, taxes, and compliance costs.

If selling direct were truly easy for farmers, many would have become retailers long ago. They would be seeing 10-20,000 customers walk through their doors daily. But retailing is a capital-intensive, risk-heavy business with constant overheads and perishable losses.

What appears as a profit gap is actually a reflection of two kinds of risk. One is biological risk on the farm. The other is logistical risk in the marketplace. Both need to be managed, not merely priced.

Punchline: When value chains lack coordination, profit behaves like water on an uneven table. It moves, but it doesn’t grow.

3. When the Farmer Raises Price from P 5 → P 8/kg

Farm-gate increase = +60 %. Each player reacts in turn.

| Layer | Prev Input (P/kg) | New Input (P/kg) | Ops & Handling (P/kg) | New Revenue (P/kg) | Profit (P/kg) | Δ Margin | Commentary |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Farmer | 5 | 5 | — | 8 | 3 | +60 % gain | Short-term relief; higher gross but may lose buyers. |

| Retailer | 5 | 8 | 15 | 23 | 3 | –2 pts | Passes cost downstream; absorbs some shrink. |

| Caterer (cooked) | 20 | 23 | 21 | 44 | 0 | –5 pts | Margins collapse; must raise plate price. |

| Consumer (plate) | 40 | 46–48 | — | 46–48 | — | Faces +15–20 % inflation on meal price. |

Observation: Farmer’s gain (+3 P/kg) triggers +15 % retail inflation and erases caterer margin.

Punchline: Farmer gains +P3/kg, caterer margin collapses, plate inflates +15–20%.

4. Comparative Margins Summary

| Layer | Profit (P/kg) @ P 5 | Profit (P/kg) @ P 8 | Change (%) | Winner / Loser |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Farmer | 0 | 3 | + ∞ | Winner (short-term) |

| Retailer | 3 | 3 | 0 | Neutral |

| Caterer | 2 | 0 | –100 % | Loser |

| Consumer | — | — | +15–20 % cost | Loser |

| System | — | — | Net – | Weaker overall |

Reflection: > Profit shifted location, not magnitude. Without coordination, the system cannot create new value — it only reshuffles scarcity.

Punchline: Price hikes shift profit location; coordination grows profit magnitude.

5. Where the Ripples Come From

Every pula that changes hands carries invisible costs:

- Retailers carry storage, energy, staff, compliance.

- Caterers carry shrinkage, prep labour, logistics.

- Consumers carry wage pressures and inflation anxiety.

Prices rise at the base without productivity growth or coordination. Each downstream player protects itself by passing on costs. They cut quality or reduce labour.

The system tightens like a chain under tension; every link creaks.

As Linda Booth Sweeney wrote in When a Butterfly Sneezes, small events lead to other happenings. These happenings connect in surprising ways.

In Botswana’s horticulture, a three-pula sneeze at the farm-gate can shake the whole plate.

Punchline: A three-pula sneeze shakes the whole plate.

6. The Structural Insight

What this case shows is not greed but structure.

The cry of the farmer (“I can’t survive on P 5/kg”) reflects a missing element. The cry of the caterer (“I can’t sell a P 48 plate”) is the same. Both are echoes of a need for a coordinated system. This system should balance supply, demand, logistics, and labour.

When systems are tight, prices can rise and everyone still profit.

When systems are loose, even generosity becomes inflation.

Punchline: Tight systems can absorb price moves; loose systems convert generosity into inflation.

7. Bridge to Part B — “When the Butterfly Sneezes”

Raising prices cannot make a weak system strong. Only productivity and coordination can.

In Part B, we follow this beetroot deeper into the soil. We explore how regenerative practices, labour productivity, and the state’s STEM backbone can transform cost into capacity.

In the end, the farmer’s hand is not the only factor that shapes the price of a plate. It is also the mind of a nation learning how its parts connect.

(End of Part A – The Ripple Effect)

Now, let’s move to Part B: “When the Butterfly Sneezes — The Unseen Players in Botswana’s Food System.”

Part B: When the Butterfly Sneezes — The Unseen Players in Botswana’s Food System

1. The quiet cause behind the farmer’s cry

In Part A, we saw how a farmer’s small price change at the soil surface affects the entire chain. This change inflates costs and erodes profits downstream.

Yet those ripples begin even deeper. They originate in the unseen conditions of the soil. The skills of labor play a role, alongside the coordination of the state.

Linda Booth Sweeney reminds us in When a Butterfly Sneezes that small causes can have big effects. This is especially true in systems that are already under tension.

In Botswana’s horticulture, the “sneeze” is often invisible. It includes an under-trained workforce, an uncoordinated logistics chain, and a budget released without a plan.

Each seems small; together they decide whether every player profits or barely survives.

2. Conventional, Organic, and Regenerative Farming Economics

| System | Yield (t/ha) | Total Cost (P/ha) | Cost (P/kg) | Farm-Gate Price (P/kg) | Revenue (P/ha) | Profit (P/ha) | Profit Margin (%) | Commentary |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional | 30 | 165 000 | 5.5–6.0 | 5.5–6.0 | 180 000 | 15 000 | 8–9 % | High synthetic inputs and fuel dependency; yields fluctuate with weather and pest cycles. |

| Organic (Certified) | 28 | 210 000 | 7.0–7.5 | 7.5–8.5 | 224 000 | 14 000 | 6–8 % | Conversion and audit costs; lower yield; depends on sustained premium demand. |

| Regenerative | 40 | 190 000 | 4.8–5.2 | 5.8–6.0 | 240 000 | 50 000 | 20–22 % | Inputs fall 10–25 % by Year 3; soil structure and water efficiency raise yield; most resilient long-term. |

(Baseline: 1 ha beetroot, open-field, Botswana; currency = BWP.)

Punchline:

Regeneration earns more not by charging more but by wasting less.

It restores both soil and solvency.

3. Labour Productivity and Cost — Botswana, Malaysia, and China

Step 1. Setting up the context

To understand how labour costs and STEM productivity shape competitiveness in regenerative (Regen) vs conventional farming — comparing Botswana to:

China (low-wage, high-productivity, strong STEM coordination), and

A non-distant, STEM-strong peer — a country shares closer institutional and social structures with Botswana. This country has managed to integrate STEM deeply into agriculture.

📍 Suitable comparison: Malaysia

Why Malaysia?

- Not culturally or politically “distant” (multi-ethnic, developing economy, democratic institutions).

- Has STEM integration across education, manufacturing, and agro-technology.

- Mid-level wages (not as cheap as China, not as high as OECD).

- Strong public-private coordination in horticulture and food exports (e.g., Cameron Highlands vegetable clusters).

- Realistic aspiration path for Botswana’s next 20 years.

Step 2. Approximate labour costs

| Country | Average Agricultural Wage (BWP equivalent/hr) | Avg Monthly (BWP) | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Botswana | P20–25/hr | P4,000–5,000 | Labour market tight; strong unions push for steady increases; relatively low productivity/hour. |

| China | P10–12/hr | P2,200–2,500 | Lower nominal cost, but very high labour productivity due to tech, mechanisation, STEM oversight. |

| Malaysia | P15–18/hr | P3,000–3,600 | Balanced wages with higher output per worker (mechanised, digitally managed farms). |

Chinese wages are half those of Botswana. However, their output per worker is often 3–4× higher. This means the unit labour cost per kg of produce ends up far lower.

Step 3. Labour cost per kg of beetroot (by system)

Let’s assume 1 hectare beetroot with ~40 tons yield (regenerative steady-state), ~30 tons (conventional).

Farm labour hours include planting, maintenance, irrigation, harvesting, grading.

| Country/System | Labour Hours/ha | Wage (BWP/hr) | Labour Cost/ha (P) | Yield (tons/ha) | Labour Cost/kg (P) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Botswana – Conventional | 1,000 | 22 | 22,000 | 30 | 0.73 |

| Botswana – Regenerative | 1,200 | 22 | 26,400 | 40 | 0.66 |

| China – Conventional | 700 | 11 | 7,700 | 40 | 0.19 |

| China – Regenerative | 850 | 11 | 9,350 | 45 | 0.21 |

| Malaysia – Conventional | 800 | 16 | 12,800 | 35 | 0.37 |

| Malaysia – Regenerative | 950 | 16 | 15,200 | 42 | 0.36 |

🌍 Observations

Unit labour costs per kg

Botswana: ~P0.65–0.75/kg

Malaysia: ~P0.35/kg

China: ~P0.20/kg

China achieves triple the efficiency despite lower pay, due to STEM-driven mechanisation, logistics integration, and continuous R&D feedback loops.

STEM intensity equals productivity

China: tech platforms link field to market daily.

Malaysia: medium-tech, government coordination, farmer co-ops with digital traceability.

Botswana: strong individual farmer effort, but low integration — data and skills sit in silos.

Regen effect

Regenerative increases labour slightly (10–20%) but offsets through yield and soil stability.

Over time, Regen reduces unproductive labour (weed management, pest crisis responses) — smart work, not harder work.

Punchline: Productivity isn’t hand strength; it’s system clarity.

Step 4. Total cost comparison (farming system + labour + inputs)

| Country/System | Total Cost/kg (P) | Key Cost Drivers |

|---|---|---|

| Botswana – Conventional | 5.5–6.0 | Inputs & labour dominant, low mechanisation. |

| Botswana – Regenerative | 4.8–5.2 | Lower inputs, higher yield, slightly more labour. |

| China – Conventional | 2.8–3.2 | Scale, automation, supply-chain optimisation. |

| China – Regenerative | 3.0–3.4 | Balanced system with government incentives, compost integration. |

| Malaysia – Conventional | 3.8–4.2 | Efficient mid-cost structure, cooperative marketing. |

| Malaysia – Regenerative | 3.5–3.8 | Integrated supply systems, stable yields, lower loss. |

Punchline: The multiplier is coherence, not cash injection.

Step 5. Interpretive insight

- Botswana’s challenge is not wage level — it’s output per hour.

We pay similar to Malaysia. We pay more than China. However, we produce only half the output because the STEM backbone and coordination spine are missing. - Regen alone is not enough. It must be coupled with STEM discipline — data, measurement, systems, integration.

- STEM turns Regen into strategy; without STEM, Regen becomes romantic.

💡 The Takeaway

A beetroot farmer in Botswana may spend the same on wages as a farmer in Malaysia. However, they produce half as much per hectare. The difference is not the hand. It is the system guiding it. STEM is present at every level, from soil testing to national logistics.

China’s system multiplies each worker’s output through data and coordination. In contrast, our system still isolates the worker. It also isolates the farmer and the policymaker. Until we bridge that gap, we will continue to pay more per kilogram. We will earn less per hour, even though our farmers work just as hard.

Our national goal should be to bring production costs down from the current P5.50–P6.20/kg to P3.50–P3.80/kg within the first three years, and to reach P3.00–P3.40/kg beyond the third year.

By the time we arrive at those levels, others will already have lowered theirs further — because efficiency compounds. It’s what athletes and craftsmen call muscle memory. When they train their muscles to work efficiently, those muscles become faster and stronger.

| Country / System | Avg Wage (P/hr) | Labour Hours/ha | Labour Cost/ha (P) | Yield (t/ha) | Labour Cost (P/kg) | Total Cost (P/kg) | Commentary |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Botswana – Conventional | 22 | 1 000 | 22 000 | 30 | 0.73 | 5.5–6.0 | High wage relative to productivity; weak mechanisation and coordination. |

| Botswana – Regenerative | 22 | 1 200 | 26 400 | 40 | 0.66 | 4.8–5.2 | More labour initially, but yield compensates; creates skilled rural jobs. |

| Malaysia – Regenerative | 16 | 950 | 15 200 | 42 | 0.36 | 3.5–3.8 | Medium wage, high STEM application; co-ops and digital traceability improve efficiency. |

| China – Regenerative | 11 | 850 | 9 350 | 45 | 0.21 | 3.0–3.4 | Low wage, strong coordination and automation; highest output per worker. |

Reflection

Productivity is not the strength of the hands but the clarity of the system guiding them.

Botswana’s labour is not expensive — it is under-directed.

4. What Happens When Botswana Combines Regeneration with STEM

If Botswana’s 30 % horticulture land (≈ 3 million ha) shifted gradually toward regenerative practices under a National Horticulture Coordination System (NHCS):

| Year | % Regen Adoption | Yield Gain (%) | National Profit (BWP Bn) | Change vs Status Quo | Commentary |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 20 | +10 | 126 | Baseline | System still fragmented. |

| 5 | 40 | +20 | 162 | +36 Bn (+29 %) | Early NHCS coordination; farmer mentoring; visible GDP effect. |

| 10 | 60 | +35 | 198 | +72 Bn (+57 %) | STEM-trained labour expands; data informs planting calendars. |

| 20 | 80 | +50 | 234 | +108 Bn (+86 %) | Full coordination spine; stable markets; rising rural incomes. |

Reflection

When the state learns to see the system as a whole, national profits rise without raising prices.

The real multiplier is not money injected, but coherence built.

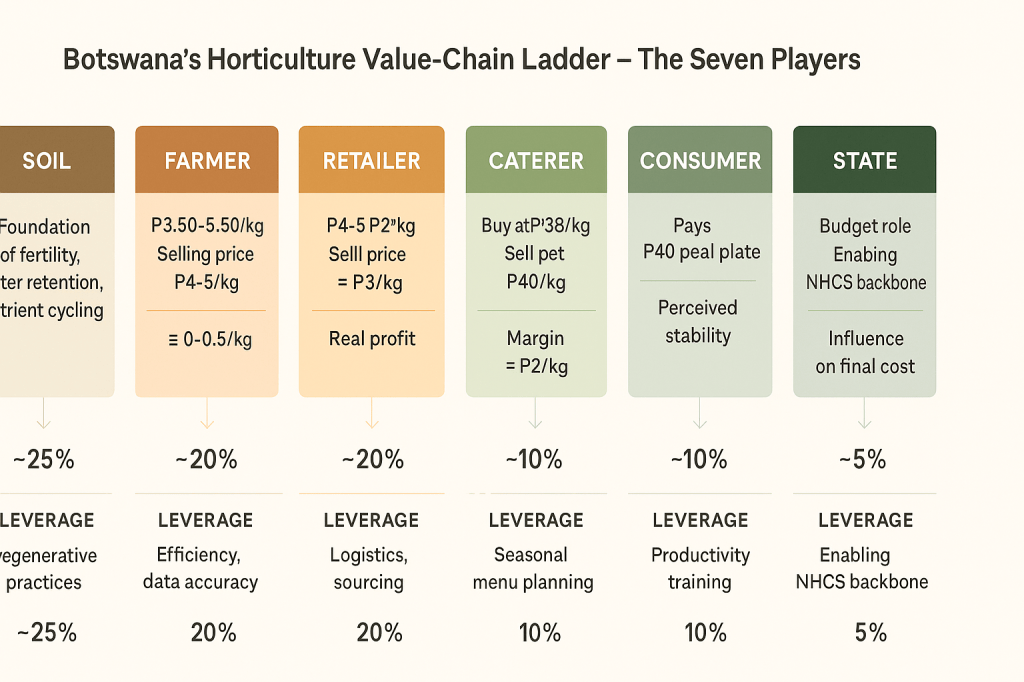

5. The Seven Players — and the Three We Forget

The painful truth is that the areas of highest leverage are often the least obvious. It is easy, as the farmer groups show each week, to toss around ideas about prices, inputs, and retail margins. Yet the power to change those pains lies elsewhere. It resides quietly in the soil. It is found in the discipline of labour and in a state that directs its STEM muscle towards agriculture.

Labour must recognize itself as more than a voice demanding fairness. It must actively participate in a global race for productivity. It is not enough to speak for higher pay when output per hour remains low. Economics cannot do miracles where labour does not first do the work itself. If productivity stalls, the entire economy suffers. Borrowing costs rise. Inflation creeps in. Every other player absorbs the shock. The wages labour receive will never be enough.

The state, meanwhile, must rediscover its long-term role as the system’s conductor. Its task is not only to distribute budgets. It must also direct STEM intentionally into agriculture. This will ensure that data, measurement, and research become daily tools of governance, not rare events.

That begins with a national shift in education. This involves playing down the dominance of non-science subjects. It also means raising the quality of mathematics and science across the board. These improvements are necessary not only for the best students but also for the average classroom. When the median student performs at the world’s upper quartile, the nation’s productivity begins to move.

In systems thinking, we say that small changes can create big results. However, finding those points of leverage is never easy. They hide in places we are least likely to look. The tip is simple: look around the room and ask who is not there. Then listen for their voices. That is where the answers often lie.

The Seven Players — and the Roles They Play

THE FORGOTTEN THREE:

The State – the unseen conductor that sets rhythm, measures, and accountability.

Labour – the hands that transform coordination into productivity. This productivity surpasses the world.

Soil – the quiet foundation; holds memory, fertility, and future yield.

WHERE WE FOCUS OUR ATTENTION:

Farmer – creates value from soil through skill and risk.

Retailer – connects that value to the market.

Caterer – translates produce into meals and employment.

Consumer – completes the loop through demand and choice.

When only the first four talk, profits fight.

When the last three join — the soil, labour, and the state — profits multiply.

In systems, the highest leverage actions are rarely found in reacting to events (e.g., “raise prices,” “import more”).

They are found in changing the relationships and information flows between parts. Soil, labour, and the state communicate and learn together.

Lesson: The “butterfly sneeze” for Botswana may not be more funding but better integration — data, training, and trust.

The system stabilises not when prices rise, but when learning, labour, and leadership align.

Punchline: When only the obvious four talk, profits fight; when soil, labour and state join, profits multiply.

6. Closing — When the Butterfly Sneezes

A small change in how we train a worker may seem trivial. Measuring soil moisture or aligning crop calendars might also seem insignificant — like a butterfly’s sneeze.

But in a fragile system, that sneeze decides whether the chain trembles or holds steady.

The path ahead is clear:

- Build the coordination spine (NHCS) so the nation’s horticulture moves as one.

- Embed STEM discipline across governance, labour, and farming.

- Let regenerative practices rebuild soils while data rebuilds trust.

Only then will every player — farmer, retailer, caterer, consumer, labour, and state — earn enough to rest easy, together.

Core Takeaway

The deepest leverage lies not in the next policy. The real change comes from altering how people see themselves in relation to one another. It also involves helping the “silent players” (soil, labour, state) regain their voices in the story.

(End of Part B – When the Butterfly Sneezes)

🪜 Botswana’s Horticulture Value-Chain Ladder — The Seven Players

Each step adds value, risk, and responsibility. The question is not who profits most — but who holds the leverage to make the entire chain prosper.

🔁 Interdependence Summary

| Player | Type of Value Added | % Influence on Final Cost | Hidden Leverage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soil | Ecological | ~25% | Regeneration & moisture retention |

| Farmer | Production | ~20% | Efficiency, timing, data accuracy |

| Retailer | Distribution | ~20% | Cold-chain & sourcing coordination |

| Caterer | Transformation | ~10% | Waste reduction, menu design |

| Consumer | Demand signal | ~10% | Conscious purchasing, feedback |

| Labour | Productivity | ~10% | Skills, STEM application |

| State | Governance | ~5% (but systemwide) | Coordination, STEM, NHCS backbone |

🪶 Reflection

A nation’s horticulture isn’t defined by the quantity of crops its farmers grow. Instead, it is defined by how well its seven players learn to work together.

Profit stops fighting when soil, labour, and the state are invited back into the conversation.

The rest — farmers, retailers, caterers, and consumers — can then finally share in what the system creates.