BATSWANA HAVE THE WORST

WORK ETHIC IN THE WORLD – REPORT

In its 2015 survey of African workers, South Africa’s Rand Merchant Bank found Batswana to be the laziest on the continent. The problem is actually more acute than that.

In the 2017-2018 Global Competitiveness Report, Botswana scores the worst among the 137 countries that are tracked by the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Index (GCI) on 12 pillars of economic competitiveness. From a list of 16 factors, respondents to the World Economic Forum’s Executive Opinion Survey were asked to select the five most problematic factors for doing business in their country and to rank them between 1 (most problematic) and 5. The results were then tabulated and weighted according to the ranking assigned by respondents. One of those factors is “Poor work ethic in national labour force.”

With a score of 19, Botswana’s national workforce (which would include those in the public and private sector as well as NGOs) emerge as standard bearers of the poorest work ethic in the world survey. Also doing poorly are Trinidad & Tobago (15.9), Brunei (14.4), Sri Lanka (11.1), Liberia (10.8), Bhutan (10.5), Seychelles (10.1), Malta (9.8), Georgia (9.7), Mauritius and Vietnam (9.5), Namibia (9.3), Bahrain (9.0), Kuwait (8.7) and United Arab Emirates and Jamaica (8.6).

WEF’s interest in labour productivity has to do with the fact that it impacts on business. A University of Botswana study by Professor John Makgala and Dr. Phenyo Thebe (“There is no Hurry in Botswana”: Scholarship and Stereotypes on “African time” Syndrome in Botswana, 1895-2011”) found that this lack of productivity has frustrated effort to attract foreign direct investment. Interestingly, there was a time when, according to literature that the authors quote, Botswana’s civil service “was generally believed to be the most efficient in the whole of the African continent.”

On a past trip to Singapore, former and late President Sir Ketumile Masire gained an appreciation on the efficiency of the country’s workers. Where a Motswana factory worker would produce one shirt within a given period of time, a Singaporean counterpart would produce six within the same period.

“This was productivity not in theory but in demonstrable terms. When we say we are not productive, this is what we meant,” Masire recalled to Sunday Standard in 2015 of this experience which would lead to Botswana benchmarking with Singapore and delegations from the two countries travelling back and forth.

As one of the Four Asian Tigers, Singapore would provide one quarter of the inspiration to establish the Botswana National Productivity Centre (BNPC). The tigers are Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan. Along the way, however, the late president appears to have given up on ever inculcating the right work ethic in Batswana. On assessing the apparent resistance, he determined that Batswana’s poor work ethic was a result of their pastoralism.

“If you look at the life of pastoralists, they don’t have a good work ethic,” he had said. The example he had cited was that beyond sinking a borehole for their livestock, letting out cattle to pasture and doing some other undemanding work, most of the time pastoralists are just lazing about as their cattle graze untended in the bush. By Masire’s analysis, this is the work ethic that has been bequeathed to modern-day Botswana.

As a University of Botswana study shows, not one productivity intervention scheme by the government has produced the desired results. In his 2015/16 budget speech, the Minister of Finance and Economic Development, Kenneth Matambo, lamented the low levels of labour productivity in Botswana. The best performers in terms of work ethic in the national labor force are from Zimbabwe and Venezuela underpinned by a perfect score.

Source: Sunday Standard. http://www.sundaystandard.info/batswana-have-worst-work-ethic-world-%E2%80%93-report Retrieved May 23, 2018

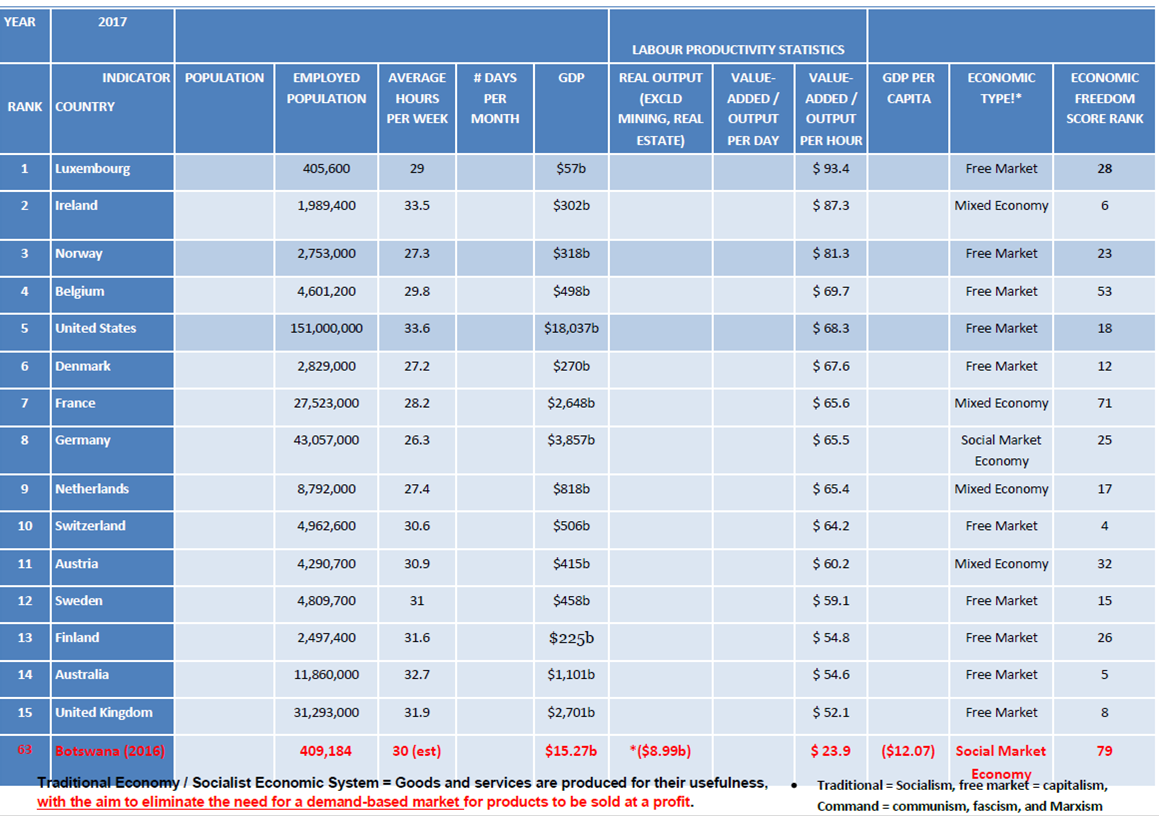

Table 1: Comparison of Botswana with 2017’s Best Global Labour Productivity Data

DID YOU KNOW? THE AVERAGE PER CAPITA PRODUCTIVITY IN BOTSWANA

LAGS THE WORLD’S PRODUCTIVE COUNTRY BY FOUR (4) TIMES?

TALKING POINTS:

Organizational Policy on Collective Responsibility and Financial Viability

1. Introduction

Economic conditions are challenging. A private organization cannot survive solely on government-issued tenders. These organizations must find alternative sources of income. To achieve long-term viability, an organization must independently generate income through domestic production and sales. It should also strategically develop export channels to meet international market demands. Organizations that fail to adopt this framework will face challenges. Continuing to depend on government-led initiatives, donors, or grants is not sustainable. They must recognize that personal incomes and livelihoods will remain uncertain. Such income sources cannot be used as bargaining tools.

Given the absence of long-term planning at the outset, urgent and decisive transformation is now required. The organization must implement immediate, radical shifts in mindset and operational practices to effectively respond to the current challenges.

2. Fundamental Organizational Principles

The next principles are essential to the organization’s integrity and must be upheld by all members. Violations occur when personal interests are prioritized over collective organizational welfare.

2.1 Collective Responsibility

The organization is a collective entity, comprising both employees and the employer. Each individual assumes equal responsibility for the organization’s success and failure upon joining. Mere attendance does not constitute work; only output that meets the employer’s standards and expectations is considered work.

Employees are not entitled to income generated by predecessors, investors, or the employer. Organizational participation demands sustained effort, alignment with the organization’s goals, and active collaboration rather than passive compliance.

Failure to internalize this principle, especially in the context of cultural and linguistic differences, can lead to miscommunication. It also weakens cooperation and causes a decline in the necessary skills for collective functioning. Such deficiencies undermine the organization’s ability to function as a cohesive and effective entity.

2.2 Authority Over Assets

The judicial system has sole authority. It determines if the organization’s assets are seized or liquidated. Employees do not have this right. Democratic processes allow employees indirect influence. Nevertheless, judicial action demands clear evidence of the employee’s direct contribution to the organization’s income generation.

Though these contributions are measurable, enforcement remains inconsistent, revealing a systemic gap. The organization does not offer exit benefits to employees without demonstrable contributions to income or growth. This is especially true during periods of financial strain or operational incapacity.

2.3 Compensation and Entitlement

Employers hire staff without long-term guarantees to sustain salaries. Still, it is structurally unsound to allow severance or exit benefits to be claimed as entitlements independent of performance. Compensation must be based on the employee’s proven ability, whether during or after employment. The employee should generate enough income to cover operational costs, return on investment (ROI), profit, and organizational growth.

Claims that exceed this threshold are unfounded. Severance is not a reward for leaving but deferred compensation for value delivered during employment. Employees are not entitled to income generated by others, like predecessors or the employer.

2.4 Salary Agreements

While salary terms are agreed upon at the time of appointment, such agreements can shield under-performance. Employees who fail to deliver measurable value still claim full compensation, leading to structural imbalance and threatening organizational sustainability.

2.5 Consequences of Non-Enforcement

Failure to set up, enforce, and adhere to these principles will lead to systemic degradation. Over time, the financial and operational stability of the organization will deteriorate, weakening its capacity to fulfill its mission.

2.6 Impact on Organizational Culture and Performance

As organizational health declines, employee morale, initiative, and innovation will suffer. Problem-solving capacity, resilience, and long-term outlook will also decline. These effects undermine both individual and collective performance, ultimately jeopardizing the organization’s sustainability.

3. Measuring Employee Contribution to Income Generation

To assess the value contributed by each employee, the following metrics should be used:

- Revenue per Employee: The total revenue divided by the number of employees. This is a key metric for assessing productivity and profitability.

- Sales per Employee: The total sales divided by the number of employees. This metric is particularly relevant for organizations focused on revenue generation.

This policy framework outlines essential principles that must be followed to ensure organizational integrity and long-term success. All employees must align with these principles and contribute to the organization’s collective well-being.

Mindsets and Beliefs (Thinking) that contribute to these challenges:

The article examines the systemic challenges impacting Botswana’s productivity. It highlights that certain prevailing mindsets and beliefs contribute to these challenges:

Reliance on Past Solutions: The belief that previous solutions will address current problems can be limiting. As noted in “Law #1: Today’s Problems Come From Yesterday’s Solutions,” this mindset obstructs innovation. It prevents the development of approaches necessary for current challenges. More here.

Quick-Fix Mentality: Seeking immediate remedies without considering long-term consequences can exacerbate issues. “Law #5: The Cure Can Be Worse Than The Disease” shows that short-term solutions lead to significant problems. These issues can intensify over time. More here.

Desire for Immediate Gratification: The expectation of achieving multiple benefits simultaneously without acknowledging necessary trade-offs can be problematic. “Law #9: You Can Have Your Cake and Eat It, Too” emphasizes the importance of recognizing trade-offs. It also highlights managing them in decision-making. More here.

Fostering a culture of continuous learning is essential. Embracing innovative solutions is also crucial. Understanding the complexities of systemic challenges further enhances productivity in Botswana.

Here’s a clearer breakdown of the ways of thinking and underlying beliefs that lead to the systemic challenges described in the article “Cracking the Botswana Productivity Code” by Sheila Singapore, with a focus on the mental models behind each:

1. Reliance on Past Solutions

Belief: “If it worked before, it will work again.”

Way of Thinking:

- Linear thinking, where cause and effect are assumed to be stable and repeatable.

- Over-reliance on tradition or precedent rather than adaptive learning.

- Lack of reflection on whether the original solution created new unintended consequences.

Result:

- Failure to deal with root causes in a changing environment.

- Resistance to innovation or systems redesign.

Related Law from the article:

Law #1: Today’s Problems Come from Yesterday’s Solutions

This law warns that yesterday’s “fixes” often sow the seeds of today’s dysfunction. Over time, without continuous learning, these solutions become entrenched, even when they no longer serve the current reality.

2. Quick-Fix Mentality

Belief: “We need to act now—any action is better than no action.”

Way of Thinking:

- Event-oriented thinking, focused on visible symptoms rather than underlying patterns.

- Short-termism, driven by urgency or performance metrics.

- Preference for symptomatic solutions instead of fundamental or structural ones.

Result:

- When resources become available, there is often a tendency to focus on “low-hanging fruit.” These are initiatives that promise quick wins or visible results. While these offer short-term gains, they often come at the expense of fundamental investments (such as building the agriculture and manufacturing economic bases). These investments are necessary for long-term, sustainable growth and, therefore, profits and return. As a result, systemic issues stay unresolved, and progress becomes cyclical, fragile, and ultimately unsustainable.

- Interventions that create new problems or worsen existing ones.

- A culture of fire-fighting rather than strategic planning.

Related Law from the article:

Law #5: The Cure Can Be Worse Than the Disease

This law illustrates how applying quick solutions can escalate the problem in the long run. It stresses the need to pause, study the whole system, and design for lasting change rather than just immediate relief.

3. Wish for Immediate Gratification

Belief: “We can have it all now—there shouldn’t be trade-offs.”

Way of Thinking:

- Magical or wishful thinking—assuming that multiple benefits can be achieved at the same time without tension.

- Disregard for systemic delays and unintended consequences.

- Inability to rank or sequence actions for sustainable impact.

Result:

- Over-promising and under-delivering.

- Undermining of trust and credibility when goals aren’t met.

Related Law from the article:

Law #9: You Can Have Your Cake and Eat It, Too—But Not All at Once

This law highlights the need for strategic trade-offs and pacing. It encourages leaders to resist the temptation of “everything, everywhere, all at once.” Instead, they should align their ambitions with system capacity and time.

Summary Thought:

Each of these beliefs reflects a limited mental model. Systems thinker Peter Senge cautions against this kind of model in The Fifth Discipline. These models block adaptive learning and creative problem-solving. Shifting toward systems thinking involves embracing uncertainty, learning from feedback, and engaging multiple perspectives for lasting, generative change.

Let’s map those unproductive ways of thinking and beliefs to leverage points that can help shift the process toward sustained productivity—using Donella Meadows’ leverage points framework (and with Fifth Discipline thinking sprinkled in):

🔁 Mapping Limiting Beliefs to Systemic Leverage Points

1. Reliance on Past Solutions

- Belief: “If it worked before, it will work again.”

- Limiting Mental Model: Fixed mindsets, failure to update strategies with changing conditions.

🎯 Leverage Point: Change the mindset or paradigm out of which the system arises (#2 on Meadows’ list)

- Actionable Strategy:

- Introduce system thinking education at leadership levels.

- Help regular reflection sessions where teams critically assess past “solutions” and their unintended consequences.

- Use learning histories or After Action Reviews to surface system feedback over time.

🧠 Fifth Discipline Insight:

Replace reactive problem-solving with “personal mastery” and “shared vision” to encourage progressive-thinking and co-created futures.

2. Quick-Fix Mentality

- Belief: “Just do something. Anything.”

- Limiting Mental Model: Immediate action is always the answer; no time for systems mapping or stakeholder engagement.

🎯 Leverage Point: Lengthen the delays to allow for system feedback and learning (#6)

- Actionable Strategy:

- Build delays into planning cycles for research, prototyping, and community engagement.

- Adopt a “double-loop learning” model: don’t just ask “Are we doing things right?” but also “Are we doing the right things?”

- Replace KPIs focused on immediate outputs with indicators of long-term ability (like “rate of organizational learning”).

🧠 Fifth Discipline Insight:

Avoid the “Shifting the Burden” archetype where symptomatic fixes distract from fundamental changes.

3. Desire for Immediate Gratification

- Belief: “We can have it all right now.”

- Limiting Mental Model: Trade-offs are unnecessary or signs of failure.

🎯 Leverage Point: Change the goals of the system (#3)

- Actionable Strategy:

- Redefine success to include sustainability, capability-building, and resilience—not just short-term gains.

- Use a balanced scorecard that includes social, learning, and environmental capital alongside financial metrics.

- Build public awareness of delayed gratification as part of national development (e.g., through storytelling or national campaigns).

🧠 Fifth Discipline Insight:

Shift to a “generative orientation”—focus on capacity to grow and evolve over time, not just on immediate results.

🔧 Practical Implementation for Botswana or Your Org:

| Limiting Belief | Suggested Intervention | Target Leverage Point | Who Leads? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Relying on outdated solutions | Systems thinking workshops; “sunsetting” old programs | Paradigm shift | Research & Policy Units |

| Quick fixes preferred | Create slow-down protocols; delay mechanisms | Delays in feedback | PMO / Strategic Planning Units |

| Wanting it all now | Align vision with phased growth plans | System goals | Board / Exec Leadership |

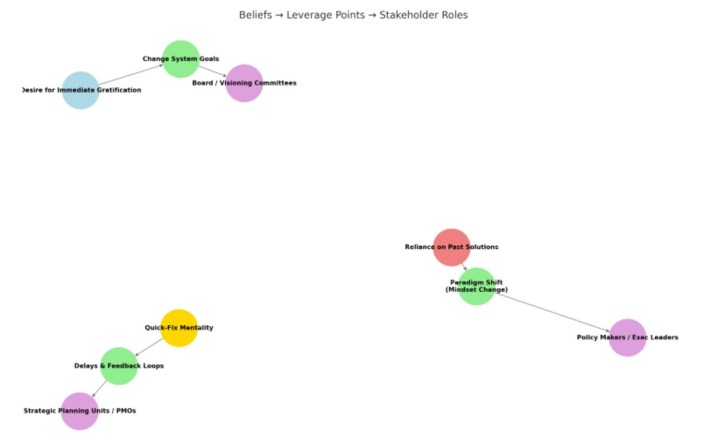

Here’s the visual causal mapping between the limiting beliefs and their corresponding systemic leverage points:

- 🔴 Reliance on Past Solutions links to a Paradigm Shift, calling for deeper mindset transformation.

- 🟡 Quick-Fix Mentality connects to Delays & Feedback Loops, urging better pacing and long-term learning.

- 🔵 Desire for Immediate Gratification maps to Changing System Goals, emphasizing a shift toward sustainability and capacity building.

Here’s the enhanced systemic leverage map, showing:

- Limiting beliefs (left),

- The leverage points needed to shift the system (center),

- The key stakeholders or institutional roles responsible for enabling those shifts (right).

This format is ideal for strategic planning sessions or policy discussions, making it easy to assign ownership and co-design interventions.

REQUIRED RESEARCH ANALYSIS

FOR DETAILS OF DATA REQUIRED FOR RESEARCH ANALYSIS FOR THIS SUBJECT, CLICK HERE.

THE FULL STORY, CLICK HERE.

[…] mammals become increasingly sexually active they produce female offsprings. Heightened sexual activity is often read by nature as a need to replace lost populations and it […]

LikeLike

[…] of Productivity – increased revenues, reduced […]

LikeLike