📅 Date Published

April 25, 2024

“Gaborone: The heart of Botswana’s economy—and its paradoxes.”

Attribute: UN Tourism

Pioneering Systems Thinking for National Transformation

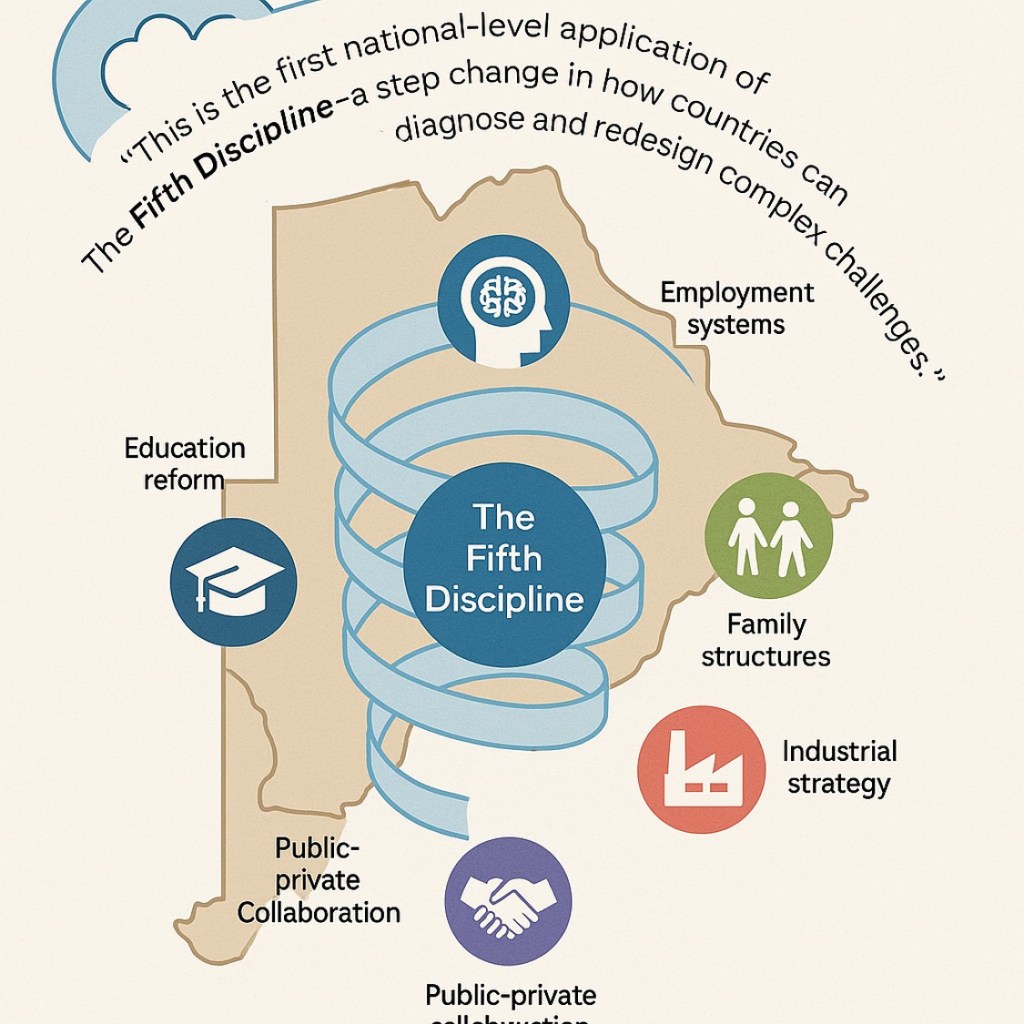

This is the first study of its kind in the field of Learning Organisation, and the first known application of The Fifth Discipline on a national economic scale. It represents a breakthrough not only for Botswana, but for the global community of systems thinking practitioners.

We are delighted to share insights into how systems thinking can be used as a research methodology—moving beyond reflection into structured, evidence-based intervention. This work pioneers new ground for how governments, businesses, and communities can approach complex, large-scale challenges.

It aligns with Peter Senge’s long-standing call to integrate systems thinking with robust research and practical application. This approach has gained recognition within the global Society for Organizational Learning (SoL) community and highlights the urgent need for more researchers and practitioner-leaders to co-create solutions across domains.

“This is not just a study. It is a prototype for how learning, leadership, and structure can come together to solve problems that have defied generations.”

Supporting Links

CORE LINK – UNEMPLOYMENT STUDY

Part 1 – Current Situation: https://sheilasingapore.blog/addressing-persistent-unemployment-in-botswana-a-systems-thinking-approach-part-1/ (You are here now)

Part 2 – Areas of Leverage Interventions: https://sheilasingapore.blog/addressing-persistent-unemployment-in-botswana-a-systems-thinking-approach-part-2/

SUPPORTING LINKS – GOVERNANCE & VALUE-CHAIN STRUCTURES AND PUBLIC SECTOR REFORMS REQUIRED TO ALLOW PRIVATE SECTOR LEAD IN ECONOMIC TRANSFORMATION:

Cross-Sectoral Growth Planning and Governance Structure: https://sheilasingapore.blog/2025/06/26/when-the-world-speaks-governance-bw/

What the Public Sector Can Do To Get Ready to Let the Private Sector Lead: https://sheilasingapore.blog/2025/06/04/when-the-world-speaks-national-development/

📖 Index – Part 1: Understanding the Design Flaw

What We’re Missing

Why unemployment persists despite decades of investment

A Systems View

Framing unemployment as a systemic design issue, not individual failure

Why the Economy Isn’t Absorbing Labour

The mismatch between GDP growth, employment, and sectoral profitability

The Circulation Crisis

How money flows out of the economy, weakening internal productivity loops

From Retail-Led Growth to Production-Led Resilience

Why agriculture and manufacturing must be restructured to drive sustainable employment

A Learning Milestone in Systems Thinking

How this study breaks new ground in national application of The Fifth Discipline

Opening Paragraph: Setting the Puzzle

Botswana has seen five decades of investment, aid, and policy reform—but unemployment remains stubbornly high. This isn’t due to lack of effort or funding. It’s something deeper—something structural.

Section 1: What We’re Missing

“Over five decades, Botswana has attracted billions in investment and international aid. The country has built infrastructure, expanded education access, and grown GDP per capita. Yet unemployment continues to rise, and the economy feels increasingly unable to absorb the talents of its people.”

Investments to-date (1960s–Present)

Since Independence, Botswana has received an estimated USD 1.2 trillion (≈ P16 trillion) in investments, government spending, and aid. Over the same period, our population has grown from approximately 580,000 in 1966 to around 2.7 million today. This translates to roughly USD 600,000 (≈ P8 million) invested per person over five decades—excluding inflation adjustments (sources: The Guardian, Reuters, Wikipedia).

As of Q1 2024, approximately 504,738 individuals are formally employed in Botswana—defined as those holding wage or salary jobs in the formal sector (VCDA.afdb.org, Trading Economics, Botswana LMO).

To put this in context:

- The average monthly wage in the formal sector is P7,149 (~USD 500) (Stats Botswana Q1 2024, ILO, Botswana LMO).

- Botswana’s total labor force is estimated at 1,173,186 individuals.

- Therefore, only 43% of the labor force holds formal employment.

This is clear evidence that decades of investment have not translated into shared prosperity.

Despite numerous policy interventions, unemployment in Botswana has remained persistently high. With just 43% formally employed, and an estimated 1.5 million working-age individuals, this leaves 57%—nearly 6 in 10 employable people—without access to sustainable income.

“Our challenge is not the absence of effort or policy. It is the absence of a structure that is designed to translate growth into widespread, sustainable income.”

“Formal employment absorbs less than half the country’s working-age population. And of those absorbed, most are concentrated in a handful of public sector or capital-intensive industries that don’t scale with population growth.”

“The labour market isn’t broken because people are lazy. It’s broken because it was never structurally designed to absorb everyone.”

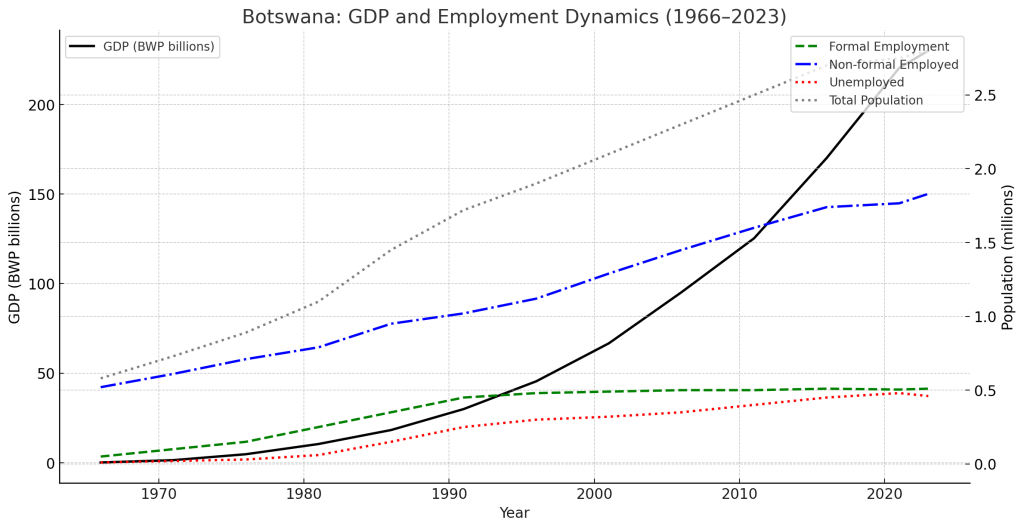

Here is the combined graph showing:

- Botswana’s GDP (in billions of BWP, left Y-axis)

- Population dynamics (right Y-axis), broken down into:

- Formal employment

- Non-formal employment

- Unemployed

- Total population

This visual illustrates:

- Sharp GDP growth over time, especially post-1990

- Stagnant formal employment despite economic growth

- Rising unemployment and non-formal employment indicate structural absorption issues

“We continue to build systems that reward GDP growth, but not labour absorption. The mismatch is systemic, not accidental.”

Section 2: A Systems View

“What if unemployment in Botswana isn’t simply the result of failed programmes or policy gaps? What if it is the predictable outcome of how the system is designed?”

(Part 1)

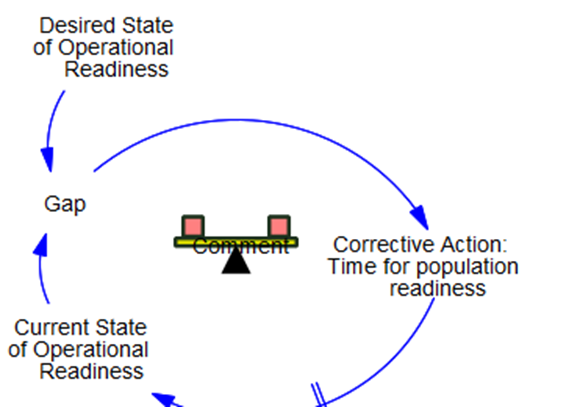

The study draws on insights from Peter Senge’s The Fifth Discipline, particularly its emphasis on systems thinking—a way of seeing problems not as isolated events, but as patterns produced by structures, delays, and feedback loops.

“Systems thinking helps us move beyond symptoms. It challenges us to ask: What are the underlying structures that keep producing the same results—even when we change the players, the funding, or the policies?”

(Part 1)

The unemployment study does not treat joblessness as a standalone issue. Instead, it approaches it as a system-wide pattern—shaped by how we educate, govern, allocate capital, and design labour absorption pathways.

“We must shift from treating unemployment as a problem to be solved, to seeing it as a system to be redesigned.”

- Circular traps within the system (e.g., weak education feeding low productivity)

“Unemployment persists not because of individual failures—but because of reinforcing loops built into the system.”

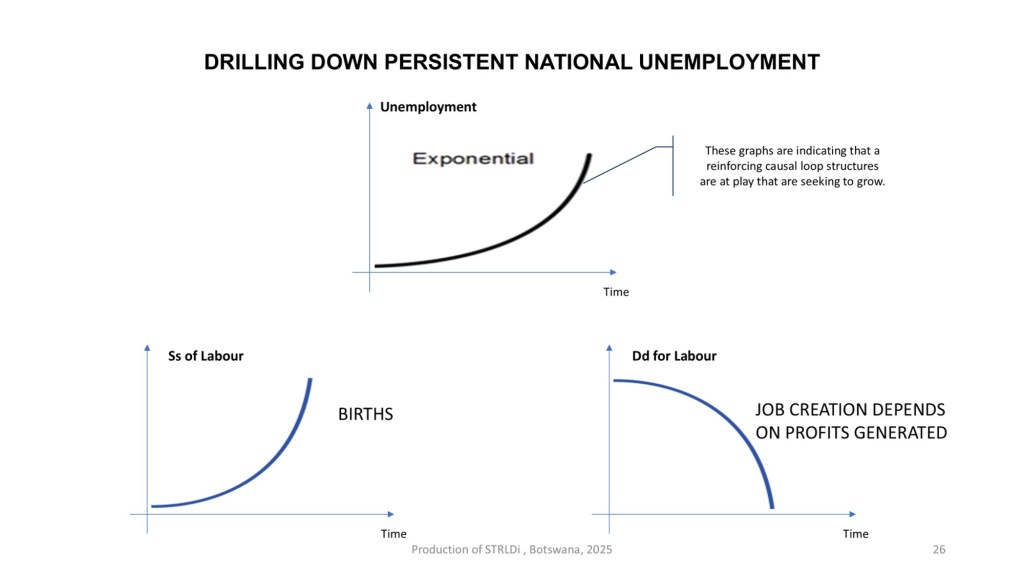

Section 3: Delays, Stocks, and Structures

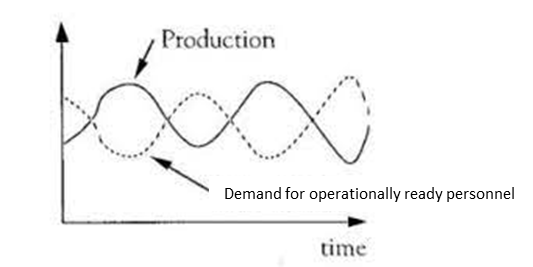

One of the most overlooked dynamics in Botswana’s unemployment crisis is delay—the long and predictable time lag between population growth and job readiness.

“We know when children are born. We know how long it takes to educate and prepare them for the workforce. Yet national economic planning treats workforce entry as a short-term policy issue, rather than a structural inevitability.”

This is a classic stock-and-flow problem:

- The stock is the growing pool of working-age individuals.

- The flow—job creation—has not kept pace with this growth.

Delays between population growth and job readiness

But the challenge runs deeper. Even when new entrants are ready to work, Botswana’s economy struggles to absorb them. The missing link? The country’s capacity to scale production and market reach.

Production Constraints and Market Access

Botswana’s enterprises—particularly in manufacturing and agriculture—have not been able to consistently meet regional and international standards in quality, speed, and output volume. This is not due to lack of ambition, but to the limited readiness of the workforce to perform at scale. Even where isolated excellence exists, system-wide performance is weak.

“When firms can’t meet standards consistently, they can’t retain or expand markets. And without markets, there’s no growth. Without growth, there’s no hiring.”

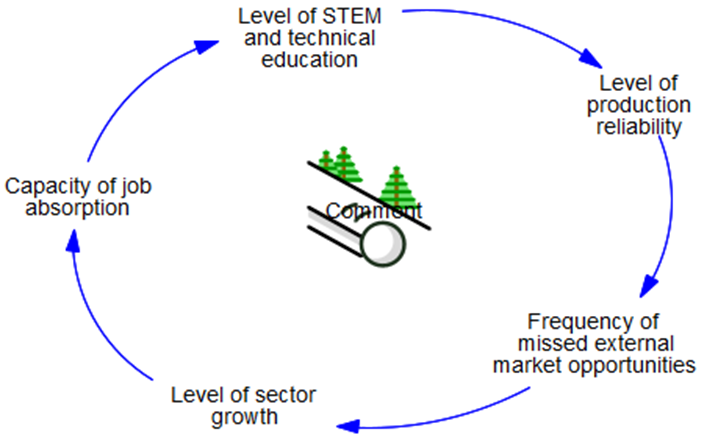

This creates a self-reinforcing loop:

As a result, firms choke themselves out of opportunity—not because of external shocks, but because of internal misalignments between labour, process, and market demand.

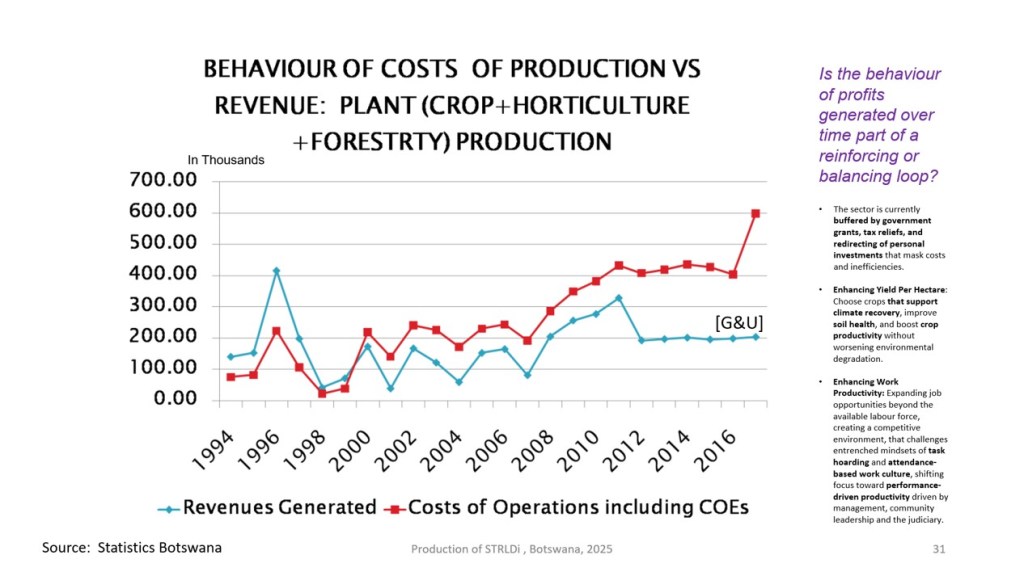

Evidence from Sector Data

The study’s behaviour-over-time graphs show that even with investment, manufacturing and agriculture have failed to generate sustained profitability as national sectors.

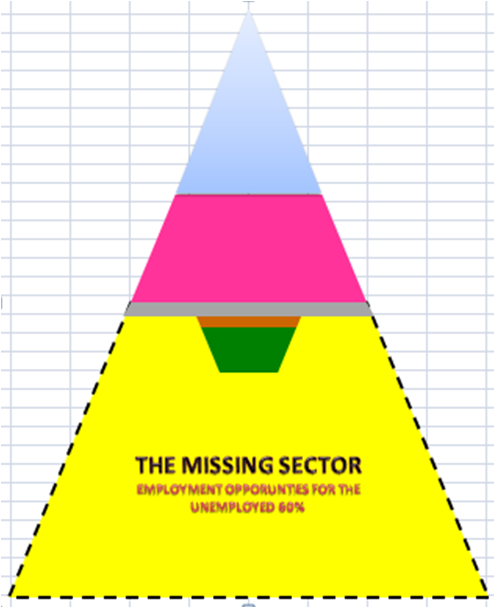

THE CAPACITY OF ECONOMIC SECTORS TO CREATE EMPLOYMENT

Since surpassing the mining sector in 2008, retail has become the leading driver of Botswana’s economy. Its continued growth reflects the rising influence of commerce, services, and consumer demand in shaping economic progress. Unlike mining, which depends on finite resources, the retail sector thrives on innovation, entrepreneurship, and the ability to respond to evolving needs. With revenues steadily outpacing costs, retail offers strong potential for job creation, business expansion, and economic resilience. Targeted investment in skills development, digital transformation, and local enterprise growth can further strengthen this vital sector.

Once the backbone of Botswana’s economy, the mining sector has faced growing volatility since the 2008 global financial crisis. Revenues have fluctuated, and lab-grown diamonds are gaining ground with global consumers due to their lower cost. While a recovery remains possible as global markets improve, the sector has shown no sustained growth over the past two decades. This prolonged uncertainty underscores the urgent need for economic diversification and greater investment in industries that offer long-term stability and resilience.

Resource-dependent emerging economies often balance raw material production with a strong manufacturing base to drive growth. Botswana, centrally located and landlocked, holds untapped potential as a regional hub for both agriculture and manufacturing, offering vital employment opportunities.

However, these sectors have struggled to take off. They contribute less than a tenth—and in some cases as little as a fiftieth—of what the retail sector generates. As a result, job creation has stalled. Agriculture and manufacturing have yet to establish profitable, scalable business models capable of supporting long-term economic growth (G&U).

To fully realize its potential, Botswana must restructure its agriculture and manufacturing sectors to ensure they are both competitive and sustainable.

By contrast, extraction-based industries (right diagram) are typically capital- and technology-intensive, employing fewer people and depleting the natural resources essential for building a resilient, job-creating economy.

(AS OF THE LAST CENSUS YEAR IN 2011) PRESENTED BY ECONOMIC SECTORS.

IT ALSO INCLUDES THE MISSING SECTORS.

IT SHOWS THE SCALE OF THE UNEMPLOYED WHEN THE FOUNDATION SECTORS ARE MISSING.

The grey, brown, and green portions represent the sizes of the manufacturing, mining, and agriculture sectors’ ability, respectively. These sectors should be readied to absorb unemployment.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Botswana

The Circulation Crisis: When Value Doesn’t Flow

When Earning Isn’t Enough: The Circulation Crisis

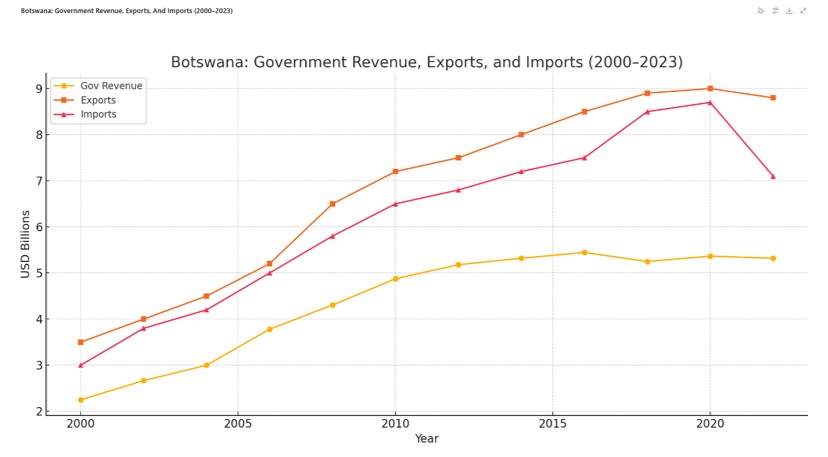

Botswana has built an impressive track record of export-led earnings and prudent fiscal management, but a deeper issue persists beneath the surface: the money we earn does not stay in the economy long enough to generate sustained impact. Instead, it exits almost as quickly as it enters—through imports, repatriated profits, external contracts, and other financial leakages. This pattern undermines the very purpose of economic growth. It’s not that Botswana doesn’t earn—it does. The problem is that those earnings don’t multiply within the local economy, depriving it of the fuel needed to create jobs, deepen industries, or uplift communities. This paper unpacks the scale of that leakage, where it goes, what remains, and what must be done to reverse it.

Exporting Wealth, Importing Dependency

It is a fair and data-backed observation that a substantial share of the income Botswana earns—whether through exports, government revenue, or trade—does not stay within the economy but instead exits rapidly. This dynamic is particularly evident in years like 2022, when Botswana exported approximately USD 8.9 billion worth of goods, yet spent about USD 8.7 billion on imports. That means nearly every pula earned through international trade was matched by a pula spent abroad. The result is a system where revenues generated through diamonds and other exports flow out just as quickly via imported fuel, machinery, vehicles, food, and services, with little absorption into domestic value chains. Without robust processing, manufacturing, or reinvestment capacity, the economy behaves like a conduit rather than a container—passing wealth through without compounding its benefits locally.

How Much Leaves, How Little Stays

In estimating the leakage, if we treat total exports (≈ USD 8.9 billion) as a proxy for total revenue, and combine import spending with factors like profit repatriation, external contract payments, and debt service, a conservative estimate suggests that at least 60–80% of this national income leaves the country. That means only 20–40% of what Botswana earns circulates internally—supporting government wages, local consumption, and limited domestic procurement. In 2022, for example, government revenue stood around USD 5.5 billion, while import bills were higher still at USD 8.7 billion—making imports roughly 158% of revenue. This points to a structural imbalance where even sovereign income is insufficient to retain wealth domestically.

The Need to Build Domestic Multipliers

What little money remains is spent primarily on public salaries, social services, and recurring operational costs, which in turn often rely on imported inputs—thereby creating additional layers of leakage. Without strengthening Botswana’s domestic production capacity—especially in manufacturing, agriculture processing, and infrastructure development—these funds will continue to create jobs and incomes elsewhere, not at home. The weak local value chain not only limits domestic job creation but also increases vulnerability to external price shocks and supply disruptions. Unless this economic architecture is reshaped to prioritize internal circulation and value capture, Botswana may continue to earn big but circulate little—leaving a growing population without the employment or enterprise opportunities it deserves.

The result? Botswana’s economic engine spins but does not pull. Resources move at the top, but do not multiply across the broader economy.

“We earn, but we don’t multiply. We produce, but we don’t distribute. This is how an economy grows on paper but feels stuck in practice.”

Section 4: What the Study Did

This study set out not merely to document unemployment trends in Botswana, but to reveal the underlying structures that continue to produce them—despite well-intentioned policies, funding, and reform efforts. It applies systems thinking, drawn from The Fifth Discipline by Peter Senge, to diagnose the national economy as a living system—one that has not been designed to absorb its people into meaningful, productive livelihoods.

The study using 20-year data:

- Tracked the disconnect between population growth and employment absorption

- Identified sector-level profitability stagnation, particularly in agriculture and manufacturing

- Mapped the structural traps and feedback loops reinforcing unemployment and low productivity

- Highlighted the circulation crisis—how value generated fails to move across the economy in a way that multiplies opportunity

“The problem isn’t a lack of effort—it’s that we’re working inside a system that was never designed to deliver the outcomes we now expect.”

At its core, the study surfaces three persistent systemic failures:

The Absorption Gap: There is no built-in pathway to absorb the growing workforce into formal, productive sectors.

The Productivity Trap: Key sectors remain underperforming, not from lack of investment, but from workforce misalignment and poor process standards.

The Circulation Breakdown: Value accumulates in isolated areas without circulating into broader economic and employment growth.

Using systems thinking tools—such as feedback loops, time delays, stock-flow structures, and archetypal traps—the study identifies leverage points that could reverse these patterns:

- Aligning education, training, and production

- Restructuring sectors to reinvest and scale

- Redesigning governance for flow, not fragmentation

Here is the closing paragraph for Part 1, crafted to bring the post to a thoughtful and anticipatory conclusion, while inviting readers forward into Part 2:

Conclusion: Preparing for the Deep Dive Ahead in Part 2

Botswana’s persistent unemployment is not the result of any single actor or decision. It is the outcome of a system whose design has not kept pace with its people. This study reveals that until job creation is structurally embedded—until sectors are rebuilt for absorption, productivity, and flow—the frustration across government, private sector, and households will continue.

But there is a path forward.

Through the lens of systems thinking, we begin to see where leverage lies—not just in programmes or reforms, but in the very architecture of how our economy functions. In Part 2, we examine the specific feedback loops, social disruptions, and sectoral misalignments that reinforce the current state—and explore how these can be shifted.

“The goal is not to fix the old system. It is to redesign the economy so that people—and their potential—are no longer left out of the future.”

Introduction to Part 2

Click here for Part 2 of the article. It covers the next:

- Consideration of Socioeconomic Factors

- Pathways for Change and Empowerment

Yes, we do. Here’s the refined write-up for the section titled:

🎓 A Learning Milestone in Systems Thinking

How this study breaks new ground in national application of The Fifth Discipline

This is the first study of its kind in the field of Learning Organisation. It marks the first large-scale application of Peter Senge’s The Fifth Discipline to a national issue—persistent unemployment—and does so using a full systems diagnosis. This milestone represents not just a personal achievement, but a breakthrough for the global community of systems thinking practitioners.

It demonstrates that the discipline of Systems Thinking can be rigorously applied beyond organizations—into the complex, cross-sectoral domain of national development. For those working on public policy, economic transformation, and institutional renewal, this work offers a new, structured framework for addressing systemic stagnation.

The study aligns with the direction advocated by Dr. Senge and the global Society for Organizational Learning (SoL): pairing systems thinking with robust research methodology. It also underscores the importance of not isolating systems thinking as a “soft” or intuitive practice, but grounding it in structured diagnosis, modelling, and evidence-based design.

🔖 Pull Quote

“This is the first national-level application of The Fifth Discipline—a step change in how countries can diagnose and redesign complex challenges.”

We welcome the opportunity to engage with researchers, educators, governments, and private sector partners who want to better understand this methodology—and consider how it might be adapted to other pressing national or regional challenges. The study offers a replicable approach for countries confronting economic exclusion, sectoral imbalance, or policy fragmentation.