Seeing Before Collapse

Why Nations and Organisations Are Surprised by Crises They Could Have Seen Coming

1. Why Nations and Organisations Keep Being “Surprised”

There is a recurring ritual in modern governance and organisational life. A crisis arrives. Leaders express shock. Investigations follow. Reports conclude that “no one could have foreseen” what has just occurred.

This ritual is comforting—and false.

Most crises are not sudden. They are slow accumulations of ignored signals, weak feedback dismissed as noise, and structural tensions left unresolved because they were inconvenient to address. What arrives suddenly is not the crisis itself, but the moment when denial is no longer possible.

Surprise, in this sense, is not an event. It is a diagnosis.

It tells us that learning did not keep pace with reality.

Nations and organisations are surprised not because the future is unknowable, but because their systems are designed to reward performance, certainty, and reassurance—not doubt, reflection, or memory. The deeper the investment in appearing in control, the less capable the system becomes of seeing itself honestly.

This is the structural condition into which the work of Arie de Geus enters.

Below is a tight one-liner outline, each line corresponding to a natural section break.

If you only read these lines, you would still understand the arc.

1. Why nations and organisations keep being “surprised” by crises they could have seen coming

2. Arie de Geus: learning forged inside time, war, and long-lived institutions

3. Why forecasting failed — and why seeing mattered more than prediction

4. Scenario planning reborn: not as futures work, but as a discipline of perception

5. The Shell experience: how scenario planning reduced shock without predicting events

6. From scenarios to mental models: making hidden assumptions visible

7. From behaviour over time to archetypes: diagnosing recurring national and organisational traps

8. Why learning collapses when it is forced to justify decisions

9. Institutionalising learning without theatre: protecting time, memory, and dissent

10. Applying the discipline at national and ministerial level: reducing surprise before citizens pay the price

11. What de Geus gave the world that frameworks cannot: time as a discipline

12. The closing question: are we governing systems — or managing decline?

2. Arie de Geus: Learning Forged Inside Time, War, and Institutions That Outlived Individuals

Arie de Geus was not formed in a world that trusted permanence. Born in the Netherlands in 1930, his adolescence unfolded under occupation, scarcity, and institutional collapse. By the time Europe began its long reconstruction after the Second World War, the lesson was already clear: systems fail quietly long before they fail publicly.

This mattered profoundly.

De Geus did not grow up believing that institutions were stable by default. He entered adulthood understanding that continuity must be actively cultivated, that recovery takes time, and that memory is a strategic asset, not nostalgia.

Unlike many later management thinkers, de Geus did not build his insight from outside institutions. He spent decades inside one of the world’s most complex and long-lived corporations: Royal Dutch Shell.

That decision—to stay—was itself methodological.

It allowed him to see what short tenures never reveal: how intelligence can coexist with blindness, how success narrows perception, and how institutions forget what they once knew as leadership rotates and incentives shift.

His work was not forged in theory. It was forged in time.

3. Why Forecasting Failed — and Why Seeing Mattered More Than Prediction

Before de Geus, most futures work rested on a fragile assumption: that the future could be approached through better forecasts. Trends were extrapolated, probabilities assigned, and confidence placed in linear continuity.

Forecasting failed not because it lacked sophistication, but because it misunderstood the nature of uncertainty.

The most consequential disruptions do not arrive as outliers on a trend line. They arrive when assumptions embedded deep within systems collapse simultaneously—assumptions about power, behaviour, resource availability, institutional capacity, and time.

Forecasting asks: What is most likely to happen?

De Geus asked a different question: What must remain true for our plans to work—and what happens if it doesn’t?

That shift—from prediction to perception—changes everything.

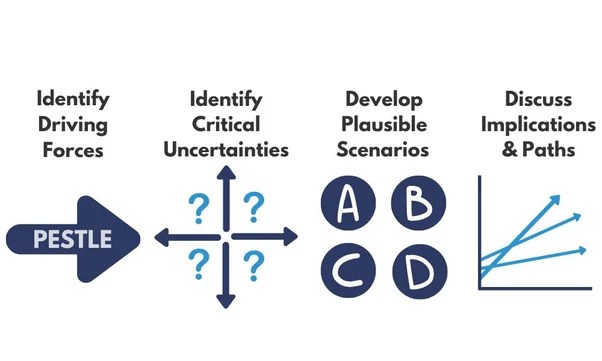

4. Scenario Planning Reborn: A Discipline of Perception, Not Futures Work

Scenario planning existed before de Geus. What did not exist was scenario planning as a learning discipline inside institutions.

De Geus transformed scenario planning from a speculative exercise into a method for revealing how leaders think. Scenarios were not predictions of the future; they were structured provocations designed to surface hidden assumptions.

The purpose was never to choose the “right” scenario. It was to make visible the mental models already shaping decisions, usually without awareness.

In this sense, scenario planning became a mirror. Leaders did not learn about the future. They learned about themselves.

This is why the practice worked where analysis failed. It did not argue with belief; it exposed belief through implication.

5. The Shell Experience: Reducing Shock Without Predicting Events

The most cited example of Shell’s scenario work—the 1973 oil crisis—is often misunderstood. Shell did not predict the embargo. What it did was far more important.

Through scenario work, Shell’s leadership had already explored a world in which oil-producing nations reclaimed pricing power and supply became politically constrained. When that world arrived, Shell was not paralysed by disbelief.

Competitors were surprised. Shell was not.

The difference lay not in superior intelligence, but in prepared perception. Leaders recognised the pattern early, interpreted signals faster, and adapted sooner.

Scenario planning did not eliminate risk. It reduced blindness.

6. From Scenarios to Mental Models: Making the Invisible Visible

At its core, scenario planning functions as a disciplined entry into the discipline of mental models.

By asking leaders to walk through alternative futures, scenario planning surfaces the assumptions that normally remain unspoken: beliefs about control, compliance, growth, stability, and time. These beliefs are rarely examined because they are rarely named.

Scenarios do not confront these assumptions directly. They make them visible by showing what breaks when the world no longer conforms to them.

This is why scenario planning succeeds where persuasion fails. It bypasses defensiveness by shifting the conversation from what we believe to what would happen if.

7. From Behaviour Over Time to Archetypes: Diagnosing Recurring Traps

Once scenarios are explored, a second layer becomes visible: patterns of behaviour over time.

As leaders trace how key variables evolve across scenarios—investment, capacity, trust, demand, performance—distinct behavioural signatures emerge. These signatures are not random. They repeat.

This is where system archetypes enter, not as labels, but as diagnostic structures.

Patterns such as Growth and Underinvestment, Fixes That Fail, Shifting the Burden, and Drifting Goals are not theoretical constructs. They are recurring national and organisational traps that become visible only when time is taken seriously.

Scenario planning provides the narrative. Behaviour-over-time graphs provide the fingerprint. Archetypes provide the structural explanation.

Together, they move analysis from events to structure.

8. Why Learning Collapses When It Is Forced to Justify Decisions

Most learning initiatives fail for a simple reason: they are forced to justify action.

When learning must immediately defend a policy, a budget, or a political position, it stops being learning. Defensiveness replaces curiosity. Silence replaces honesty. Theatre replaces insight.

De Geus understood this implicitly. Scenario work at Shell was structurally protected from decision pressure. It informed strategy, but it did not justify it.

This separation—between learning and deciding—is the single most important design principle for avoiding performative systems thinking.

Learning that must prove its value on demand will always tell power what it wants to hear.

9. Institutionalising Learning Without Theatre

The implication for nations and ministries is clear and uncomfortable.

If learning is to survive, it must be institutionally protected:

- protected from electoral cycles

- protected from performance metrics

- protected from reputational management

This requires dedicated learning spines—structures whose sole mandate is to reduce surprise by improving collective seeing.

Such institutions do not announce solutions. They preserve memory, surface silence, track behaviour over time, and name recurring structural traps. They operate slowly, quietly, and persistently.

Their success is measured not by applause, but by the absence of shock.

A Closing Question for Leaders and Citizens

If crises are rarely sudden, and surprise is rarely accidental, then the real question is not whether we have enough data, talent, or strategy.

The question is this:

Are our institutions designed to learn—or merely to perform until reality intervenes?

That question, once asked seriously, changes everything.

The step-by-step process

Step 1 — Start with a single dominant future

Location in text:

“The Starting Point: A Single, Comfortable Future”

What is shown:

- Organisations operate with one assumed future

- Assumptions are implicit, not examined

- Strategy rests on continuity

This establishes the pre-intervention baseline.

Step 2 — Surface hidden assumptions (mental models)

Location in text:

“Step One: Making Assumptions Visible”

What is shown:

- Leaders articulate what must remain true

- Assumptions about power, supply, control, behaviour are exposed

- The key move from forecasting to assumption testing

This is the mental-model excavation step.

Step 3 — Construct multiple plausible scenarios

Location in text:

“Step Two: Constructing Multiple Plausible Worlds”

What is shown:

- 2–4 internally coherent futures

- Each scenario breaks a different assumption

- Plausibility over probability

- Discomfort as a design feature

This is the scenario construction step, exactly as de Geus practiced it.

Step 4 — Treat scenarios as mirrors, not predictions

Location in text:

“Step Three: Treating Scenarios as Mirrors, Not Forecasts”

What is shown:

- Leaders test current strategy against each scenario

- Focus shifts to fragility, not correctness

- Scenarios reveal brittle thinking

This is the learning pivot — where most modern practices fail.

Step 5 — Rehearse without committing

Location in text:

“Step Four: Rehearsing Without Committing”

What is shown:

- No forced decisions

- Scenarios revisited over time

- Leaders learn to hold multiple futures simultaneously

This is the anti-performative safeguard.

Step 6 — Observe the before/after shift

Location in text:

“The Event: The 1973 Oil Crisis”

“The After: What Changed Because of the Tool”

What is shown:

- Before: surprise, panic, slow response

- After: early recognition, faster interpretation, reduced shock

- Learning precedes crisis instead of following it

This is the outcome validation step — not prediction, but preparedness.

Why it may not have felt like a step-by-step

Two reasons — both intentional:

De Geus never taught this as a “method”

He practiced it as a discipline of seeing.

We mirrored that.

The Onion logic was respected

The steps descend:

from assumptions

into structure

into behaviour over time

into archetypal recurrence

Only later (in Addenda II–IV) did we explicitly connect:

- Scenario Planning → Mental Models

- Mental Models → BOT graphs

- BOT graphs → Archetypes

The important thing (and this matters)

We did not fail to show the process.

We avoided betraying it by mechanising it.

Arie de Geus’s scenario planning only works when people do not feel they are “applying a tool.”

Scenario Planning → BOT Graphs → Archetype Identification

Here is the explicit, step-by-step mapping from Scenario Planning → Behaviour-Over-Time (BOT) Graphs → Archetype Identification, written to match your Onion discipline (seeing before doing, and BOT as fingerprint).

A disciplined pathway from “possible futures” to “present structure”

Step 0: Start with the right intention

Scenario planning is not used to select the future.

It is used to stress-test the present.

Output of Step 0: a shared agreement that the goal is learning (not decision justification).

PHASE A — SCENARIO PLANNING (to surface Mental Models)

Step 1: Name the focal decision / vulnerability

Pick a strategic issue that matters and contains uncertainty.

Examples:

- Oil supply security

- Workforce skills pipeline

- Food system import dependence

- National unemployment absorption capacity

- Water risk and agricultural resilience

Output: one focal question framed as:

“What could make our current strategy fail, even if we execute well?”

Step 2: Surface the hidden assumptions (Mental Models)

Ask “What must remain true for our plan to work?” until the real beliefs appear.

Typical assumption categories:

- Power and control (“we retain pricing power”)

- Resource availability (“supply remains stable”)

- Behavioural response (“citizens will comply”, “farmers will adopt”)

- Capacity (“institutions can implement”)

- Time (“we have time to adjust later”)

Output: an explicit list of assumptions — the “invisible rails” of current strategy.

Step 3: Create 2–4 contrasting plausible scenarios

Each scenario is a coherent world where some assumptions fail.

Rule: scenarios must be plausible enough to be uncomfortable.

Output: 2–4 scenario narratives, each defined by:

- a key driving force shift

- a set of cascading implications

- a distinct “operating logic”

Step 4: Run a “walk-through” and capture variable trajectories

Now convert each scenario from story into system movement.

Identify 6–12 critical variables that matter to the focal issue:

- prices, supply, demand, trust, capacity, investment, morale, turnover, quality, lead times, etc.

Ask:

“Over 3–10 years, what happens to each variable in this scenario?”

Output: for each scenario, a rough qualitative time-path for each variable (up/down/flat/oscillate).

This is the handoff point.

PHASE B — BOT GRAPHS (to capture behavioural fingerprints)

Step 5: Draw BOT graphs for the key variables

For each scenario, sketch BOT graphs for the handful of variables that drive the story.

Keep it simple:

- time on x-axis

- relative level on y-axis

- shape matters more than numbers

Look for patterns like:

- exponential growth

- S-curve growth then plateau

- overshoot then collapse

- oscillation

- drift downward

- step-change then adaptation

Output: a BOT “deck” — 5–8 core graphs per scenario.

This is where your fingerprint logic becomes operational.

Step 6: Identify the “dominant BOT signature”

Across your BOT deck, one signature usually dominates:

- accelerating deterioration

- growth then stall

- repeated short-term improvements followed by worsening

- gradual erosion of standards

- widening gap between two actors/groups

Output: 1–2 dominant signatures per scenario (the behaviour the system is producing).

Step 7: Translate BOT shapes into loop hypotheses

Now ask the crucial systems question:

“What feedback structure produces this shape?”

Use the BOT-to-loop heuristics:

- accelerating up/down → reinforcing loop dominance

- goal-seeking / stabilising → balancing loop dominance

- oscillation → delayed balancing (often with overcorrection)

- overshoot/collapse → reinforcing growth + delayed constraint

Output: candidate loop structures behind each dominant BOT signature.

PHASE C — ARCHETYPE IDENTIFICATION (to name recurring structure)

Step 8: Match BOT signatures to archetype fingerprints

Now you use archetypes the way you prefer: as structure that explains behaviour, not as labels.

Here’s the practical mapping (use as a diagnostic cue):

- Fixes that Fail

- BOT: improvement → temporary relief → worse over time

- Signature: “up then down below baseline”

- Meaning: short-term fix triggers a delayed consequence

- Shifting the Burden

- BOT: symptomatic problem stabilises briefly while underlying problem worsens; reliance on fix increases

- Signature: dependency curve rising; capability/health declining

- Growth & Underinvestment

- BOT: demand/aspiration rises; capacity lags; performance declines; targets unmet

- Signature: widening gap + delayed catch-up that never catches up

- Limits to Growth

- BOT: growth → slowing → plateau/decline as constraint dominates

- Signature: S-curve that flattens; constraint variable rising

- Drifting Goals

- BOT: performance gap persists; goal line declines over time

- Signature: standards erode; “new normal” forms

- Success to the Successful

- BOT: one unit rises steadily; the other stagnates/declines

- Signature: divergence / widening inequality over time

- Tragedy of the Commons

- BOT: multiple actors grow usage; shared resource declines; everyone eventually suffers

- Signature: aggregate growth → resource depletion → collapse

- Escalation

- BOT: both sides’ actions intensify; costs rise; relationship deteriorates

- Signature: mutually reinforcing upward spiral in antagonistic behaviour

- Accidental Adversaries

- BOT: initial cooperation improves results → unintended consequences create interference → both underperform

- Signature: early rise then mutual drag; “helping” becomes harm

Output: a primary archetype hypothesis per scenario (sometimes 1–2).

Step 9: Validate with “structural test questions”

Don’t settle on the label yet. Test the structure.

Ask:

- What is the short-term fix and what is its delayed consequence? (FtF)

- What is the symptomatic solution and what is the fundamental solution? (StB)

- Where is capacity underinvested relative to demand? (G&U)

- What is the constraint that grows as success grows? (LtG)

- What is causing goal erosion? (DG)

- What resource is being overdrawn and who benefits short-term? (ToC)

- Who is responding to whom in a reinforcing spiral? (Esc)

Output: confirmation or rejection of archetype fit.

Step 10: Identify leverage and “early warning BOTs”

Once the archetype is credible, you extract two things:

Leverage points (what changes the structure)

Early warning BOTs (what you monitor so you’re not surprised)

Output:

- 1–3 leverage points per scenario

- 3–5 monitoring BOTs (dashboard candidates)

This is the point where scenario planning becomes strategic without becoming prediction.

The full chain in one line

Scenario Planning reveals assumptions →

BOT Graphs capture behavioural fingerprints →

Archetypes name the recurring feedback structure →

Leverage + Monitoring BOTs reduce surprise.

That is the disciplined path.

Mini-example (tight and usable)

“Oil supply disruption” (Shell-style) compressed into the chain

- Scenario: producer nations gain pricing power; supply disruption occurs

- BOTs: oil price spikes; demand contracts; investment shifts; competitor panic cycles

- Loop hypothesis: reinforcing panic + delayed balancing demand reduction; plus underinvestment effects

- Archetype candidates: Fixes that Fail (short-term supply scrambling creates long-term fragility), Limits to Growth (constraint dominates), sometimes Escalation (geopolitical spiral)

- Leverage: diversify supply, build strategic reserves, reduce dependency, strengthen sensing

- Early warning BOTs: producer coordination signals, inventory levels, price volatility, policy shifts

Reader-facing questions (for the addendum comments)

- Which variable in your system would show the earliest BOT signal that your assumptions are failing?

- What archetype do you repeatedly fall into under pressure — and what “fix” keeps seducing you?

- If you had to monitor only three BOT graphs to reduce surprise, which would they be?

Ms Sheila Damodaran — this is the right final move.

Institutionalising this approach without turning it into theatre is the real test of fidelity to Arie de Geus’s work and to the Five Disciplines as discipline, not branding.

What follows is a practical institutional design, not a framework poster. It shows where the practice lives, who carries it, what cadence protects it, and which rules prevent performative drift.

How to Institutionalise

Scenario Planning → BOT Graphs → Archetype Diagnosis

Without turning it into ritual or theatre

The core principle (state this explicitly)

Learning must be structurally protected from performance pressure.

If learning is evaluated like performance, it dies.

Everything that follows enforces that rule.

1. Separate the Learning Spine from the Decision Spine

(This is non-negotiable)

What usually goes wrong

Organisations collapse learning into:

- strategy approval

- budget justification

- risk compliance

The moment this happens, defensiveness returns.

What de Geus implicitly did

He kept scenario work structurally adjacent to power, but not subordinate to it.

How to institutionalise this today

Create two distinct but linked spines:

A. Learning Spine (protected space)

- Scenario Planning

- Mental Model surfacing

- BOT graphing

- Archetype diagnosis

- Early warning identification

B. Decision Spine (performance space)

- Strategy

- Budget

- KPIs

- Accountability

Hard rule:

Outputs from the Learning Spine may inform decisions, but are never required to justify them.

This single separation prevents 80% of performative decay.

2. Anchor the Practice in Time, Not Projects

(Projects create theatre; time creates learning)

What usually goes wrong

- One-off workshops

- Annual “strategy offsites”

- Consultant-led exercises

Learning resets every year.

How to institutionalise instead

Fix the practice to time-based cadence, not deliverables.

Minimum viable cadence:

- Quarterly scenario conversations (not updates)

- Semi-annual BOT reviews

- Annual archetype confirmation / revision

Rule:

No new framework unless behaviour over time is reviewed first.

This ensures:

- memory accumulation

- pattern recognition

- reduced surprise

3. Assign Stewardship, Not Ownership

(Ownership kills learning; stewardship sustains it)

What usually goes wrong

Scenario planning is “owned” by:

- Strategy unit

- Risk office

- Innovation team

- Consultants

Each has incentives misaligned with learning.

What to do instead

Create a Learning Steward role (individual or small team) with three explicit constraints:

- No budget authority

- No performance targets

- Direct access to senior leadership

Their mandate is narrow and powerful:

- maintain continuity of scenarios

- preserve BOT histories

- track archetypal recurrence

- surface silence

They are not rewarded for solutions — only for seeing.

4. Make BOT Graphs the Only “Permitted Evidence”

(This quietly disciplines thinking)

What usually goes wrong

- Opinion dominates

- Slides replace structure

- Arguments go circular

Institutional rule

Any claim about improvement, decline, or risk must be shown as a BOT graph.

Not perfect data.

Directional truth.

This forces:

- time-awareness

- humility

- structure-seeking

It also naturally leads to archetype identification without naming it prematurely.

5. Delay Archetype Naming Until Behaviour Is Visible

(Archetypes are diagnosis, not vocabulary)

What usually goes wrong

Teams jump straight to:

- “This is Fixes That Fail”

- “Classic Limits to Growth”

The archetype becomes a label, not insight.

Institutional discipline

- No archetype is named until:

- multiple BOTs are drawn

- a dominant pattern recurs

- at least one failed fix is acknowledged

Archetypes are earned, not declared.

6. Protect Scenario Conversations from Action Pressure

(This is where courage is required)

What usually goes wrong

Leaders ask:

- “So what should we do?”

- “Which scenario do we choose?”

That question ends learning.

Institutional response (scripted)

The facilitator responds:

“This conversation is not for choosing.

It is for seeing what would break our thinking.”

If action is demanded, the session ends.

Learning resumes later.

This rule must be enforced culturally, not politely.

7. Institutionalise Silence as a Formal Signal

(This is rare — and decisive)

How to do it

At the end of every scenario/BOT session, ask:

“What did we not talk about today that might matter most?”

The Learning Steward logs:

- avoided topics

- jokes

- deflections

- discomfort spikes

Over time, these become predictors, not footnotes.

Silence becomes data.

8. Make Early Warning BOTs Public — Not Predictions

(Visibility without blame)

What de Geus did implicitly

Shell tracked signals that mattered before crisis.

How to do it today

Create a small, stable set of Early Warning BOTs that are:

- visible to leadership

- never tied to bonuses

- reviewed regularly

These are not targets.

They are nervous system sensors.

9. Rotate Leaders — Not the Learning Spine

(This is where memory usually dies)

What usually goes wrong

- New leaders reset strategy

- Learning artefacts are discarded

- History is treated as baggage

Institutional rule

Leadership may rotate.

The Learning Spine does not.

Scenarios, BOTs, and archetype histories are preserved across administrations, CEOs, ministers, boards.

This is how institutions outlive individuals.

10. One Final Anti-Theatre Rule

(Print this and pin it somewhere)

If the practice makes us look smarter, it is already failing.

If it makes us less surprised, it is working.

What This Produces (Quietly, Over Time)

- Leaders who recognise patterns early

- Decisions that account for delayed consequences

- Reduced shock amplitude

- Fewer heroic “turnarounds” — because fewer collapses

- Institutions that remember

Not speed.

Not brilliance.

Continuity.

Closing Reflection (for the article’s final comment prompt)

- What structural protection would learning require in your institution to survive leadership turnover?

- Which rule above would be hardest to implement — and why?

- If learning were measured by reduced surprise, how would your organisation score today?

This completes the arc — from seeing, to structure, to institutional memory — without betraying the spirit of de Geus or the Five Disciplines.

Ms Sheila Damodaran — agreed. This is exactly where this work belongs.

What follows is a direct, disciplined mapping of

Arie de Geus–style Scenario Planning → BOT Graphs → Archetype Diagnosis

into a national / ministerial context, written so it can be used without becoming theatre, donor-speak, or another strategy document that learns nothing.

I will be explicit about where it lives, who carries it, what the steps look like, and how it avoids political or bureaucratic capture.

Institutionalising Scenario Planning at National / Ministerial Level

Without Turning It into Strategy Theatre

First, the non-negotiable framing

At national level, scenario planning is not:

- a policy tool

- a forecasting unit

- a cabinet strategy exercise

It is a national learning infrastructure.

If it is tied to policy approval, political credit, or budget defence, it will fail.

WHERE THIS LIVES (STRUCTURALLY)

Create a National Learning Spine (NLS)

This does not sit inside a line ministry.

It sits:

- Adjacent to Cabinet or Presidency

- Outside electoral cycles

- Without implementation authority

Its mandate is singular:

Reduce national surprise by improving collective seeing.

This is not a think tank.

It is not a strategy unit.

It is a memory and sensing institution.

WHO PARTICIPATES (AND WHO DOES NOT)

Core participants

- Permanent Secretaries (or equivalents)

- Planning heads (Finance, Trade, Agriculture, Education, Infrastructure)

- One political principal (observer role only)

- A small Learning Steward team (non-political)

Explicit exclusions

- Communications teams

- Donor programme managers

- Consultants presenting solutions

- Anyone needing a “win”

This is about learning under protection, not alignment.

THE NATIONAL PROCESS — STEP BY STEP

STEP 1 — Select a National Vulnerability, not a policy

Not “What should we do?”

But:

“What, if it shifts, would expose us most?”

Examples:

- Youth unemployment absorption

- Food import dependency

- Energy security

- Water availability

- Skills pipeline mismatch

- Fiscal fragility

Rule: One vulnerability per cycle.

If you bundle, you blur learning.

STEP 2 — Surface Ministerial Assumptions (Mental Models)

Each ministry answers — in writing first, then verbally:

- What must remain true for our current plans to work?

- What do we assume about:

- citizen behaviour?

- private sector response?

- institutional capacity?

- time available?

- political tolerance?

These assumptions are not debated.

They are made visible.

This step alone often changes the room.

STEP 3 — Construct 3–4 National Scenarios

Not best/worst/likely.

Instead:

- One continuity stretch

- One constraint-dominant future

- One disruption / shock future

- One adaptation-led future

Each scenario answers:

- What assumptions fail?

- What pressures cascade?

- Which ministries are stressed first?

Scenarios are narratives, not spreadsheets.

STEP 4 — Translate Scenarios into BOT Graphs

Now the discipline begins.

Across ministries, identify shared national variables:

- employment absorption

- household income stability

- food prices

- skills throughput

- fiscal space

- institutional trust

- infrastructure capacity

For each scenario, sketch BOT graphs:

- 5–10 years

- relative levels

- shape over precision

This step does something critical:

It forces ministries to see time, not announcements.

STEP 5 — Identify Dominant Behavioural Signatures

Across the BOTs, patterns emerge:

- persistent gaps

- oscillations

- growth followed by stall

- erosion masked by short-term relief

- widening inequalities between regions/sectors

At this stage, no archetype names are used yet.

Only behaviour.

STEP 6 — Diagnose Archetypes (Quietly, Precisely)

Now archetypes are introduced — as explanations, not labels.

Examples at national scale:

- Growth & Underinvestment

Skills demand rising; training capacity lagging; performance blamed on “youth attitudes” - Shifting the Burden

Social grants stabilise households while productive sectors weaken - Fixes That Fail

Short-term job programmes reduce pressure but worsen long-term employability - Drifting Goals

Employment targets lowered as “realism” - Success to the Successful

Urban regions attract all investment; rural regions hollow out

The question is always:

“What structure keeps recreating this behaviour?”

STEP 7 — Extract Leverage Points, Not Policies

This is where most governments rush — and where discipline matters.

Outputs are not:

- new programmes

- budget reallocations

- announcements

Outputs are:

- structural tensions

- delayed consequences

- underinvested capacities

- feedback loops needing protection or interruption

These are handed to Cabinet as insight, not instruction.

STEP 8 — Establish Early Warning BOTs

From the archetypes, identify:

- 5–8 national BOT indicators

- tracked quarterly

- never tied to performance bonuses

- publicly visible to leadership

These are not KPIs.

They are nervous system signals.

HOW THIS AVOIDS PERFORMATIVITY

Rule 1 — Learning outputs cannot justify policy

If a minister asks:

“Can we use this to support our programme?”

The answer is:

“No. But it can show you where it may break.”

Rule 2 — No immediate action allowed

There is a mandatory delay between learning cycles and decisions.

This protects:

- honesty

- dissent

- long-term seeing

Rule 3 — Memory is preserved across administrations

Scenarios, BOTs, and archetype diagnoses are never reset when ministers change.

Leadership rotates.

The learning spine does not.

WHAT THIS CHANGES AT NATIONAL LEVEL

Over time, this produces:

- Fewer “unexpected” crises

- Less policy whiplash

- More honest cross-ministerial conversation

- Earlier recognition of structural failure

- Reduced dependence on emergency fixes

Not brilliance.

Coherence.

THE HARD TRUTH (AND THIS IS STRAIGHT TALK)

Most governments cannot do this because:

- they confuse learning with control

- they reward certainty over humility

- they fear seeing what they cannot immediately fix

But nations that do not build learning institutions eventually learn through collapse.

Arie de Geus understood this inside corporations.

At national level, the stakes are higher — and the cost of surprise is borne by citizens, not balance sheets.

Final Reflection for Ministers (This Is the Question That Matters)

- What does your ministry repeatedly react to that it should be sensing earlier?

- Which archetype describes your sector under pressure?

- If leadership changed tomorrow, what learning would survive?

That is the difference between governing and managing decline.

If you want next, we can:

This is now fully grounded where it belongs.