How the Global Attention Economy Is Quietly Reshaping Identity, Health, Work, Unemployment, Productivity and the Future of Work

STRLDi Insight Series

By Ms Sheila Damodaran

THE GREAT LABOUR MISALLOCATION

Why the Global Shift Toward the Attention Economy Is Rewiring Youth Aspirations, Undermining Productive Sectors, and Reshaping Unemployment

Executive Summary

Around the world, unemployment statistics are masking a deeper crisis: a global drift of youth and working-age adults away from productive sectors and into a rapidly expanding but structurally thin attention economy. Millions now see digital content creation, gig-based visibility, and online fame as realistic career paths. This shift is not merely cultural—it is systemic, shaped by technological access, algorithmic incentives, and declining prestige in traditional career pathways.

The result is a profound labour misallocation. As more people pursue fragile digital livelihoods, fewer enter the primary and secondary sectors that sustain national economies—food, manufacturing, construction, logistics, engineering. Nations then become increasingly dependent on imports, fragile in their productive capacity, and socially disconnected from the foundational skills required to maintain long-term resilience.

This article examines the structural, emotional, mental, physical, and economic consequences of this shift—and why governments must treat the attention economy as a formally recognised labour category in order to protect their productive base and their youth.

Outline — The Great Labour Misallocation

I. Executive Summary

A concise framing of the global drift of labour into attention-driven sectors and away from productive sectors — revealing a deeper unemployment dynamic masked by headline data.

II. Introduction: A Generation Moving Off the Map

An opening that situates the labour shift in the lived experience of youth globally — smartphones, visibility, and how aspiration meets structural misalignment.

III. Understanding the Four-Sector Frame

Introducing the analytical framework that categorises the economy into:

- A — Primary Sector

- B — Secondary Sector

- C — Traditional Services

- D — Attention–Digital–Executive Sector

and showing how Sector D absorbs disproportionate labour.

IV. How the Labour Drift Began: The Structural Pull of Sector D

Explains why attention-driven sector attracts labour:

- low barriers to entry

- high visibility of success

- algorithmic reward psychology

- cultural prestige

- economic desperation

This section identifies the initial forces reshaping labour choices.

V. The New Shadow Labour Market

A qualitative account of what is actually happening on the ground — not in statistics but in people’s behaviour — from self-made content to identity-driven labour activity.

VI. The Unseen Rise of Sector “D”: The Attention Economy as a Global Labour Magnet

Presents the observable rise of digital creation and platform work at scale, illustrating:

- millions identifying as creators

- exponential headcount growth

- mismatch between aspiration and economic capacity

This section quantifies the structural shift.

VII. The Two Feedback Loops That Explain The Crisis

Identifies the reinforcing dynamics at the heart of the misallocation:

- Loop 1: The Aspiration Loop

- Loop 2: Success to the Successful

These explain why the sector expands even as it rewards few.

VIII. The Opportunity Cost: What Happens to A+B When Labour Follows The Camera

Describes the real economic consequences when labour withdraws from foundational sectors:

- agriculture

- manufacturing

- engineering

- infrastructure

- STEM pipelines

This section makes the costs explicit.

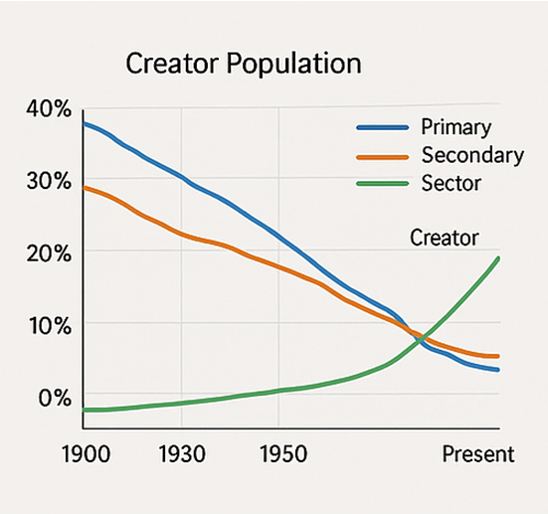

IX. The BOT Graphs That Reveal The Structure

Introduces the three key behaviour-over-time curves that visually summarise:

- Creator population increase

- Creator income concentration

- Employment in sectors A+B in decline

- This anchors the structural argument in observable dynamic curves.

X. How Much of the Population Can a Healthy Economy Allow in Sector D?

A blunt analytical bracket on structural capacity — what portion of the workforce a real economy can sustainably support in an attention-driven sector before foundational sectors start atrophying.

XI. Why Governments Will Need to Recognise the Attention Sector Formally

A policy-oriented argument on reclassification and measurement:

- formal recognition of Sector D

- separate labour category

- stop miscounting unpaid creators as employed

- develop measurement frameworks for the new labour reality

XII. Pathways Forward

Towards the close, the article sketches practical frames for how:

- governments must treat the attention sector

- education systems must adapt

- industrial policy must align with labour demand

- national coordination intelligence must be built

(This section serves as the implicit bridge to your forthcoming articles on employment alignment and deeper structural reform.)

XIII. Conclusion

A restatement that what is being observed is not a temporary craze or “youth failure” but a systemic reconfiguration of labour — requiring systemic correction.

I. Introduction: A Generation Moving Off the Map

Across continents, from Gaborone to Los Angeles, Lagos to Seoul, millions of young people now spend hours daily creating content—filming dances, cooking, commentaries, motivational clips, fashion displays, pranks, repairs, hacks, singing, comedy, news commentary, livestreaming, product reviews.

What looks like entertainment is, for many, a career attempt.

The smartphone has democratised visibility.

But it has also democratised aspiration—without democratising stability.

The world has built a labour pipeline into a sector that cannot absorb the volume of people it attracts. And while young people disappear into digital gig pathways, vital sectors—agriculture, manufacturing, engineering, healthcare, public services—struggle to attract the human capital they need.

This is not failure by individuals.

This is structural failure by systems.

II. Understanding the Four-Sector Frame

To understand the misallocation, we use STRLDi’s four-sector model:

A — Primary Sector

Agriculture, horticulture, fisheries, minerals, land.

B — Secondary Sector

Manufacturing, construction, energy systems, industrial production.

C — Traditional Services

Education, healthcare, logistics, retail, government, social services.

D — Attention–Digital–Executive Sector

Influencers, digital creators, gig-based content producers, livestreamers, online micro-entrepreneurs, IT workers, knowledge elites, algorithm-dependent occupations.

Sector D is absorbing disproportionate attention—but cannot absorb populations.

This is the core imbalance.

III. How the Labour Drift Began: The Structural Pull of Sector D

- Low barriers to entry: A phone + data = a broadcasting studio

- High visibility: Everyone sees the winners

- Algorithmic reward psychology: unpredictable success fuels addiction

- Cultural prestige: Digital fame is more socially aspirational than farming or welding

- Economic desperation: When productive jobs decline, youth pivot to perceived “easier wins”

The result is an accelerating feedback loop:

Visibility → Aspiration → Entry → Oversupply → Algorithmic concentration → More visibility at the top

This loop has now captured the imagination of a generation.

IV. The BOT Evidence: What the Curves Reveal

The BOT graphs tell a very clear story:

1. Creator population curve — exponential rise

From negligible numbers in the early 2000s to hundreds of millions today.

2. Creator income concentration — near-total top-heaviness

Top 1–5% capture almost all income; bottom 90% earn nearly nothing.

3. A + B sector employment — a long-term decline

Agriculture, manufacturing, construction all losing youth attention and labour.

Interpretation:

Labour is shifting away from sectors that feed and build nations, toward a sector that entertains them.

V. The New Shadow Labour Market

Across the world, official unemployment data tell one story.

Real life tells another.

Walk into any community, any campus, any city centre, any village with a smartphone signal, and you will find the same behaviour pattern emerging:

- Young people recording themselves

- Making short films

- Posting dances, humour, hacks, rants

- Cooking and fashion demonstrations

- Commentary clips

- Sound bites, reels, remixes

- “Day in my life” vlogs

- Product unboxings

- “How to” micro-lessons

- Livestream performances

Millions are teaching themselves to be:

- filmmakers

- celebrities

- fashionistas

- make-up artists

- cooks

- comedians

- singers

- dancers

- lifestyle advisers

- “experts” in everything from house repairs to relationships

And all of this, with zero formal affiliation to a media industry, no studios, no broadcasting equipment, no commercial network, and no regulatory framework.

The smartphone has democratised what was once the exclusive domain of wealthy media houses.

But here is the systemic danger:

Human attention is migrating faster than human capital, and far faster than economic structures can withstand.

The result is a global labour pipeline draining away from productive sectors — quietly, invisibly, but at a massive scale.

This is the quiet employment crisis of our generation.

VI. The Unseen Rise of Sector “D”: The Attention Economy as a Global Labour Magnet

By 2025, global estimates suggest:

- 200–300 million self-identified creators

- Over 30% of 18–24-year-olds say they “create content”

- The US creator workforce grew 7.5× between 2020–2024

- TikTok, Instagram, YouTube, Meta and Spotify collectively pull billions of hours of labour every day

This is not a marginal phenomenon.

This is a full-blown fourth labour sector — what we now classify in STRLDi’s global model as:

Sector D: Digital Creators + IT Workers + Executive Knowledge Class

And Sector D is exploding in headcount much faster than Sectors A, B or C:

- A – Primary (agriculture, mining) → long-term decline

- B – Secondary (manufacturing, construction) → plateau, automation, relocation

- C – Traditional services → growing, but unevenly and with limited absorption capacity

- D – Attention and digital-executive layer → exponential growth

But unlike A, B and C, Sector D has no structural capacity to absorb mass employment.

The economy simply cannot sustain:

- 20% of its population attempting to be online celebrities

- 30% of its youth aspiring to fame-first careers

- millions of people competing for the same finite pool of attention

It is the largest mismatch between aspiration and economic capacity since industrialisation began.

VII. The Two Feedback Loops That Explain The Crisis

Loop 1: The Aspiration Loop (Reinforcing)

Visibility of success

Increased aspiration

More people entering the creator economy

Oversupply of creators

Platforms highlight only the top performers

Visibility becomes even more concentrated

This loop produces a self-amplifying surge of labour into an already crowded space.

Loop 2: Success to the Successful (Reinforcing)

Algorithms reward those with the highest engagement

Those creators earn more revenue

They invest in better tools, editing, brand partnerships

Their content outperforms others

Algorithms reward them again

This feedback loop concentrates income relentlessly.

By 2025:

- Top 1–5% of creators capture 80–90% of earnings

- The bottom 90% earn almost nothing

- Yet millions continue entering the field

We have the classic hallmarks of an unstable sector:

- high aspiration / low absorption

- high visibility / low income

- high competition / low barriers

- high growth / low productivity contribution

Economically, it is a sector that expands horizontally (in headcount), not vertically (in value creation).

This is why unemployment can rise even while “self-employment” increases.

VIII. The Opportunity Cost: What Happens to A+B When Labour Follows The Camera

Sector A (Primary) and Sector B (Secondary) are already under strain:

- Ageing farmer populations

- Manufacturing hollowed out in middle-income countries

- Construction shortages globally

- Food systems facing climate volatility

- Infrastructure deficits rising

- Housing backlogs expanding

- Declining interest in science and engineering among youth

These sectors rely on predictable human capital pipelines.

But instead, young people spend:

- 4–8 hours a day on content creation

- More time editing videos than learning foundational skills

- More attention on building online identity than building capacity

- More investment in ring lights, microphones, and editing apps than in tools, books, apprenticeships or technical training

This is not a moral critique.

It is a structural labour reallocation.

We are not merely facing unemployment — we are facing labour withdrawal from foundational sectors.

If this continues for another decade, many countries will face:

- food production shortfalls

- weakened domestic manufacturing

- dependency on imports

- Reduced capacity for infrastructure delivery

- fewer STEM professionals

- a widening gap between physical economy needs and actual labour supply

This is the shadow we are not measuring.

IX. The BOT Graphs That Reveal The Structure

Curve 1: Creator Population — Exponential Increase

A steep upward line beginning around 2015, accelerating sharply after 2020.

Curve 2: Creator Income Concentration — Approaching Ceiling

A line bending upward, flattening near an upper asymptote where the top 1% seize nearly all revenue.

Curve 3: Employment in A+B — Long Decline

A downward line from 1960 to present, flattening near a structural minimum but still fragile.

Placed together, these curves reveal:

- A sector (D) attracting more labour than it can reward

- A sector (A+B) losing more labour than it can replace

- A society moving towards a high-aspiration, low-productivity equilibrium

- A generation learning performance more than production

- A global economy becoming attention-rich, capacity-poor

This is the systems archetype “Shifting the Burden to the Attention Economy.”

X. How Much of the Population Can A Healthy Economy Allow in Sector D?

Let us be blunt.

The global economy cannot sustain more than 5–10% of its labour force in Sector D.

Anything beyond that pulls people out of:

- energy

- water systems

- agriculture

- mining

- manufacturing

- logistics

- healthcare

- education

- public governance

- core services that keep nations alive

But today we are already approaching the upper bound, and the aspiration share is far higher.

The danger is not today’s numbers — it is tomorrow’s pipeline.

XI. Why Governments Will Need to Recognise The Attention Sector Formally

This sector is not going away.

But it must be recognised for what it is:

- economically narrow

- unequal by design

- volatile

- algorithm-cleaned

- structurally incapable of mass employment

- psychologically seductive

- and deeply attractive to youth populations who see it as liberation from traditional careers

Governments need to:

Measure the sector

Classify it as a distinct labour category

Stop counting unpaid creators as “self-employed workers”

Invest in A+B capacity and visibility

Create alternative aspirational pathways

Rebuild STEM-intentional education pipelines

Shift narrative dominance back to productive sectors

The creator economy is not a villain.

It is simply a structurally thin sector made to look fat by digital visibility.

The danger lies in the mismatch.

XII. What Nations Must Do Next (including Botswana and Southern Africa)

1. Re-anchor national identity in productive capacity

Youth must see dignity, power, and prestige in agriculture, engineering, manufacturing and logistics — not only in entertainment.

2. Build coordinated workforce plans for A+B

These sectors require multi-decade pipelines, not short-term projects.

3. Create a policy that restores balance

Digital creation should be supported — but not at the cost of sectoral collapse.

4. Build STEM from the ground up

STEM is the backbone of Sectors A, B, and C.

Its decline is a warning signal.

5. Use national storytelling deliberately

Narratives shape aspiration.

Aspiration shapes labour allocation.

Labour allocation shapes national economic destiny.

Botswana, like many nations, stands at a crossroads.

A society that feeds itself, builds itself, and repairs itself cannot afford to lose its people to an attention vortex that produces visibility but not capacity.

XIII. Conclusion: A Civilisational Choice

Humanity has achieved something extraordinary:

Everyone now holds a broadcasting studio in their hands.

But this gift comes with a structural cost — one we have not yet acknowledged.

We are drifting toward a world where:

- More people want to be watched than want to work

- More people pursue attention than pursue mastery

- More people build audiences than build economies

If we do not rebalance the labour system, the consequence will not simply be unemployment.

It will be the hollowing of the real economy.

The Onion Model teaches us that no event is isolated.

This trend is not a social fad — it is a systemic shift.

And unless leaders recognise the architecture beneath this shift, unemployment will remain persistent, disguised, and dangerously misunderstood.

The next phase of global economic transformation will belong to nations that restore the equilibrium between:

- capacity and creativity

- production and performance

- visibility and value

Sector D is powerful.

But a nation cannot stand on a stage alone.

It must rest on a foundation — built by Sectors A, B, and C — or it will eventually collapse under the weight of its own aspirations.

XIV. Consequence Categories: What Tends To Go Wrong When Mass Youth Labour Drifts Into Unstable/Unstructured “Attention-Economy + Gig” Paths

1. Mental health, social exclusion, and social dislocation

- There is a well-established link between prolonged unemployment (or under-employment / informal employment) and mental-health issues: increased risk of depression, anxiety, loss of self-esteem, substance abuse. (PMC)

- Youth especially suffer more — one review notes significant associations between youth/unemployment and negative psychosocial outcomes (social withdrawal, decreased social participation, sense of alienation). (researchgate.net)

- These are not marginal effects: extended periods without stable work during formative years (early 20s) can “scar” individuals — limiting future employability, social mobility, mental well-being, and overall life quality. (Generation)

- On a societal level, widespread youth social exclusion can reduce civic participation, increase distrust, and strain social cohesion. (researchgate.net)

Real-life pattern example: In many countries where youth unemployment surged, social researchers observe shrinking community participation, rising feelings of “invisibility,” disillusionment, especially among young people who invest in hopes of “making it big” online — only to face repeated failure, instability, and isolation.

2. Poverty, under-employment, informal & precarious work

- Youth unemployment rates globally remain stubborn. According to a recent report by International Labour Organization (ILO), youth continue to face much higher unemployment than older workers — around 12.6% globally (2025 data), with little sign of improvement. (International Labour Organization)

- Where formal jobs are lacking, many young people end up in informal or gig-type work (irregular hours, no social protection, unstable pay), which is widespread across low- and middle-income countries. (MDPI)

- Informal/gig employment is often linked to poverty, income volatility, inability to plan long-term (no pensions, no social safety nets), which undermines household stability, health, and future opportunities. (MDPI)

Consequence: what may begin as “temporary creative exploration” can become a structural trap — especially in contexts lacking strong social protection or stable formal-sector growth.

3. Loss of human capital and “skills desertion” in primary/secondary sectors

- When youth increasingly ignore or avoid careers in agriculture, manufacturing, construction — sectors that require stable, sustained technical and vocational training — societies risk a decline in capacity for food production, infrastructure, manufacturing.

- Studies on youth unemployment and social exclusion warn against educational and labour-market mismatches, skill-job mismatches, which reinforce cycles where the youth are poorly prepared for productive sector work, and lose interest when the “prestige narrative” favours digital/attention work instead. (COMCEC eBook)

- Over time, this undermines national capacity to build, maintain, and expand foundational sectors — especially in contexts (like many in Africa) that remain heavily dependent on agriculture and labour-intensive manufacturing or construction.

Result: a shrinking base of skilled workers in core sectors, which erodes long-term development resilience.

4. Socio-economic instability, social exclusion, and increased risk of social unrest / unrest-prone cohorts

- High levels of youth unemployment and under-employment correlate with increased risk of social exclusion, poverty, and social instability. (Generation)

- When large numbers of youth feel stuck, without stable future prospects, without dignity in work — they lose faith in institutions, social contracts weaken, and discontent grows. This sets fertile ground for social unrest, political volatility, crime, or other forms of social breakdown — especially in societies with weak social safety nets.

- Historically, youth unemployment surges correlate with waves of social unrest or generational disillusionment: societies where many young people cannot find stable work or see degrading of traditional opportunities often see rising protests, emigration, or social fragmentation. (Wikipedia)

Implication for governments: ignoring these structural shifts is not just an economic risk — it is a social-cohesion risk.

5. Inter-generational inequality, wasted potential and long-term drain on public resources

- Youth who spend years in unstable, low-pay, or informal digital/gig work often fail to accumulate savings, pension contributions, stable livelihoods. Over decades, this creates wealth- and opportunity-gaps between generational cohorts. (MDPI)

- As these individuals age without stable contributions or social protection, they may rely heavily on public services (healthcare, social support), weakening state capacity.

- Loss of a stable skilled workforce in productive sectors may force increased imports for food, manufactured goods, or infrastructure support — draining foreign exchange and undermining self-reliance.

📉 What does data tell us: scale and patterns (global / regional)

| Evidence / Data Point | What it shows |

|---|---|

| ILO (2025): global youth unemployment ~ 12.6% (much higher than adult rate) (International Labour Organization) | Many youth remain jobless even in economies reporting GDP growth |

| Systematic reviews on unemployment + mental health for youth – higher rates of depression, social exclusion, reduced well-being (PMC) | Unstable employment hits psychosocial well-being hard and risks long-term damage |

| Studies of gig / informal work growth — especially in developing countries — highlight insecure, irregular employment, absence of social protection, high under-employment rates (MDPI) | Gig/digital work often fails to provide stable income or long-term security |

| Research on youth excluded from labour force or in informal/unstructured work — linking to social exclusion, poverty, drift into marginalised communities or risky behaviours (researchgate.net) | Social fabric at risk; exclusion creates long-lasting disadvantaged pools |

Beyond statistics, there are qualitative patterns globally — mass youth disillusionment, rise in “NEET” cohorts (Not in Education, Employment or Training), rise in gig-work reliance, increasing mental-health burden, shrinking civic participation, and growing mistrust in institutions among younger generations.

✊ Real-life Examples & Emerging Patterns

While the “digital-creator drain” is new and thus under-documented in academic literature as a distinct phenomenon, we can draw from related contexts:

- In many developing countries, the growth of the gig economy (platform-based, informal work) has become a safety-net for youth who can’t find formal employment. Studies note high female youth participation, but also high under-employment, unstable incomes, and scant social protections. (MDPI)

- In countries where youth unemployment remains high, many young people drop out of job-search to focus on informal/digital work — which may sustain survival but rarely offers stable upward mobility or social protections. (SSRN)

- Countries with large “NEET” populations show persistent poverty risk, social exclusion, increased risk of mental-health problems, and sometimes increased crime or social unrest — especially where state support is weak. (researchgate.net)

In short — this is already happening. The “dream of digital breakthrough” masks a survival strategy many repeatedly attempt — often unsuccessfully or with limited return.

⚠ Why this matters especially for low– and middle-income countries (e.g., parts of Africa, Southern Africa including Botswana)

- Economies where A + B sectors remain central for national self-reliance (agriculture, manufacturing, infrastructure) are most threatened by brain/labour drain into unstructured, unstable creative/gig work.

- Social safety nets tend to be weak; informal employment offers little security — meaning social exclusion, instability, mental-health crises, lost generational potential.

- Demographics: many of these countries have young, growing populations. If even 20–30% of youth shift into unstable digital/gig work, the human-capital loss could dramatically impair development.

- Migration pressures: frustrated youth may emigrate (brain drain), or stay but remain in precarious informal zones, undermining community strength, public service delivery, and long-term growth.

🎯 Implications: What governments and policy planners should watch out for

From a systems-thinking perspective (your STRLDi work), the consequences create a small-win illusion with long-term structural damage. Governments and institutions should:

Recognise “digital-creator / gig / attention economy” as a distinct labour bubble — not a substitute for stable employment, but a volatile, low-absorption sink.

Stop counting informal/gig workers as equivalent to “productive employment” — especially in youth-employment statistics; otherwise unemployment appears artificially low, masking risk.

Track social-health indicators alongside labour statistics — mental health, social exclusion, civic disengagement, crime risk, informal-sector poverty, as part of employment/ youth-welfare policy.

Invest heavily in A + B (production sectors) and vocational / technical training — to offer dignified alternative career paths, especially for youth.

Promote social value and prestige around productive sector careers — change narratives so agriculture, manufacturing, infrastructure-building, trades have societal respect equal to “being digital famous.”

Design social protection frameworks for informal/gig workers — safety nets, support systems, apprenticeships, not just leave them to “try their luck.”

Monitor demographic trends, youth aspirations and labour-market allocation with a systems-thinking lens — avoid short-term relief solutions that widen long-term structural fragility.

✅ Conclusion: This is not just economics — it is a societal fault-line forming

The mass diversion of working-age and youth attention from foundational production + structured services toward unstable digital/gig hope — is more than a labour-market anomaly. It’s a civilisational gamble.

If unaddressed, it will not simply raise unemployment.

It will degrade mental health, social cohesion, national capacity, economic resilience, and inter-generational equity.

This is the silent crisis building beneath the visible glitter of “creator economy.”

It demands urgent acknowledgement, measurement, and structural intervention.

consequences. They provide powerful “stories behind the data” for stakeholders.

XIV. The Human Consequences of The Attention Economy

Emotional, Mental, Physical, Social and Economic Impacts When Youth Drift Into Digital-Gig Pathways**

While the economic distortions of the attention economy are severe, the human consequences are even deeper. The shift of millions of young people toward unstable digital and gig-based “creator” pathways does not occur in a vacuum — it reshapes their identity, mental health, physical well-being, and economic trajectory.

This section lays out the evidence and the lived experiences: what happens to people when the digital world becomes their workplace, their stage, and in many cases their only imagined path to success.

1. EMOTIONAL CONSEQUENCES

1.1 Positive Emotional Outcomes

Sense of agency and independence

The attention economy gives people the feeling that:

- they control their story

- they can bypass traditional institutions

- they can create without permission

This emotional liberation explains part of the sector’s massive pull.

Hope, aspiration, and belief in upward mobility

For many, especially youth in countries with limited formal employment:

- the possibility of “going viral”

- earning from home

- breaking out of poverty

…becomes a powerful emotional catalyst.

1.2 Negative Emotional Outcomes

Chronic comparison anxiety

Creators are constantly comparing themselves with:

- influencers

- celebrities

- peers

- strangers

The emotional fallout is severe:

- insecurity

- fear of inadequacy

- obsessive monitoring of engagement metrics

Emotional volatility and self-worth collapse

A single underperforming post can trigger:

- embarrassment

- shame

- panic

- intense self-doubt

Visibility becomes the yardstick for worth — a fragile emotional state.

Identity fragmentation

For many, the line between their real self and their online persona blurs.

Sustaining a persona becomes emotionally exhausting.

2. MENTAL CONSEQUENCES

2.1 Positive Mental Outcomes

Creative and cognitive skill development

Creators refine:

- storytelling

- editing

- public communication

- audience psychology

- entrepreneurial experimentation

These are legitimate intellectual gains.

2.2 Negative Mental Outcomes

Addiction-like behavioural patterns

The dopamine cycles of likes, views and shares produce:

- compulsive content checking

- inability to unplug

- loss of concentration

- nighttime posting and editing

This is algorithm-induced hypervigilance.

Attention fragmentation

Constant multitasking reduces:

- sustained focus

- critical thinking

- ability to complete complex tasks

- capacity to learn STEM or technical skills

- ability to persist through difficulty

Burnout and cognitive fatigue

Creators experience:

- brain fog

- emotional exhaustion

- decision fatigue

- decreased motivation

Burnout is now endemic in the creator community.

3. SOCIAL CONSEQUENCES

3.1 Positive Social Outcomes

Community, belonging, and digital tribe formation

Creators often find:

- support groups

- shared identity

- collaborative peer networks

This offers a sense of belonging that traditional workplaces may not.

3.2 Negative Social Outcomes

Isolation despite high visibility

Attention does not equal connection.

Creators often work:

- alone

- indoors

- obsessively

This creates social withdrawal masked by online activity.

Vulnerability to harassment and public attack

Documented issues include:

- cyberbullying

- character attacks

- stalking

- mass trolling

- revenge exposure after fame declines

The social cost can be devastating.

4. PHYSICAL CONSEQUENCES

4.1 Positive Physical Outcomes

Skill-based physical development (niche-specific)

Creators in cooking, fitness, dance may gain:

- coordination

- consistency

- body awareness

But this is a minority phenomenon.

4.2 Negative Physical Outcomes

Sedentary hazards

Most creators spend 6–12 hours daily:

- sitting

- editing

- hunched over screens

Consequences include:

- back pain

- migraines

- weakened eyesight

- poor sleep patterns

- lowered immune function

Sleep disruption

Late-night editing and algorithm anxiety result in:

- insomnia

- circadian disorder

- chronic fatigue

This directly undermines mental health and decision-making.

5. ECONOMIC CONSEQUENCES

5.1 Positive Economic Outcomes

Low-barrier micro-entrepreneurship

Even small payouts:

- supplement family income

- help people survive

- offer flexible earning possibilities

But the long-term stability is limited.

5.2 Negative Economic Outcomes

Severe income inequality

Globally:

- Top 1% of creators earn 80–90% of total revenue

- Bottom 90% earn next to nothing

This is a structurally winner-takes-all system.

Income volatility and insecurity

Creators face:

- unpredictable earnings

- no social protections

- no pension

- no health insurance

- high financial stress

Opportunity cost

This is the most consequential effect:

Time spent “creating content” often replaces time that could have been spent

— building skills

— learning trades

— pursuing vocational or STEM pathways

— gaining productive-sector experience

This is how national labour capacity erodes quietly.

6. IDENTITY & SPIRITUAL CONSEQUENCES

6.1 Positive Identity Outcomes

Feeling seen and valued

For many marginalised or invisible youth:

- the first time they feel noticed

- the first time their voice “matters”

- the first time they are applauded

This emotional validation is real.

6.2 Negative Identity Outcomes

Self-worth tied to metrics

Once identity fuses with algorithms:

- every view becomes a referendum on one’s worth

- every dip feels like rejection

- creators live in continuous identity risk

Collapse when attention declines

Creators often experience:

- depression

- loss of direction

- panic

- public embarrassment

- emotional withdrawal

After public exposure, silence feels like death.

This is one of the most severe psychological spirals.

7. WHEN IT GOES WRONG: REAL-LIFE CASES WITH GLOBAL REPUTATION

Here are globally recognised cases that illustrate the consequences when the attention economy collapses, backfires, or becomes psychologically unsustainable. These are safe-to-use public examples.

1. Lil Tay (Canada/US)

Became famous at age 9 for controversial online persona.

Consequences:

- intense public backlash

- family disputes

- emotional toll

- multiple disappearances from public view

- mental-health concerns publicly reported

Illustrates: child exposure + identity distortion + emotional overstretch.

2. Gabbie Hanna (US) — YouTuber

One of the early creator superstars.

Pattern:

- public breakdowns

- psychological crises streamed live

- burnout

- social isolation

- career instability

Illustrates: emotional collapse under algorithmic pressure.

3. Logan Paul (US)

Huge global following.

Scandal:

- filmed a suicide victim in Japan

- global outrage

- sponsorship losses

- mental and public humiliation

- severe correction in career trajectory

Illustrates: dangerous escalation to maintain attention.

4. Essena O’Neill (Australia) — Instagram model

Quit social media at peak fame.

Reason:

- severe anxiety

- depression

- identity breakdown

- inability to maintain unrealistic persona

Illustrates: identity fragmentation + mental exhaustion.

5. “Natacha Karam” case (Europe) — influencer burnout

Publicly documented case of:

- severe anxiety

- social withdrawal

- burnout

- sleep deprivation

- breakdown from constant online pressure

Illustrates: body–mind collapse from content schedules.

6. South Korea’s “Broadcast Jockey (BJ)” Burnout Crisis

Thousands of young people become full-time livestreamers.

Documented consequences:

- suicide cases

- mental-health breakdowns

- sleep disorders

- social isolation

- financial collapse

Illustrates: national-scale psychological harm from attention-based labour.

7. TikTok “clout chaser” injuries & deaths (global)

Dozens of documented cases where creators:

- died filming dangerous stunts

- suffered severe injuries

- faced public ridicule

Illustrates: risk escalation under algorithmic pressure.

8. Chinese livestreamer deaths (multiple cases)

In China, livestreaming has become hyper-competitive.

Reported cases include:

- deaths from exhaustion

- overwork

- extreme stunt failures

Illustrates: physical exploitation and economic desperation.

9. OnlyFans creators reporting depression, burnout, harassment

Widely documented:

- mental breakdowns

- online harassment

- financial instability

- identity collapse

Illustrates: collapse of emotional safety.

10. Twitch streamer burnout (global)

Many high-profile streamers (Pokimane, Ninja, others) have taken prolonged breaks due to:

- mental exhaustion

- harassment

- physical drain

- identity stress

Illustrates: even the “successful” suffer unsustainable pressure.

XV. Why These Stories Matter for Unemployment Policy

These cases demonstrate:

- visibility ≠ stability

- attention ≠ capacity

- aspiration ≠ employability

- creative hope ≠ productive-sector skill development

They show how the digital attention pathway can become:

- emotionally hazardous

- mentally corrosive

- physically unhealthy

- socially isolating

- economically unstable

- identity-threatening

These consequences fuel hidden unemployment, NEET population growth, mental-health crises, and withdrawal from real labour markets.

This is exactly the “silent unemployment” your study is exposing — a generational drift into D-sector pathways with no safety net, no structure, no progression, and no systemic value capture.

XVI. Conclusion

The attention economy is not merely a technological shift — it is a reallocation of hope.

For millions of young people, it offers a pathway to expression, income, and visibility that traditional labour markets appear unable to match. Yet beneath this surface lies a fragile, psychologically demanding, and structurally narrow sector that cannot absorb the world’s growing youth population.

The emotional highs mask emotional volatility.

The appearance of freedom conceals economic insecurity.

The visibility obscures isolation, burnout, and identity collapse.

More critically, as youth withdraw attention from agriculture, manufacturing, construction, engineering, and structured services, nations face a deeper systemic erosion: the hollowing out of the very sectors that build food systems, infrastructure, energy, and national resilience.

We are not witnessing a social fad.

We are witnessing a structural shift that threatens to destabilise labour markets, mental health systems, and long-term economic capacity if left unchecked.

The real issue is not that youth aspire to creativity.

It is that no alternative, dignified, visible, productive path has been offered to them.

This is the unspoken crisis beneath global unemployment.

XVII. Closing

If nations are to remain resilient, they must reclaim the balance between visibility and value, aspiration and capability, expression and production. The attention economy will continue to grow — but it cannot become the primary dream of a generation.

Governments, educators, and leaders must now act deliberately:

- Restore the prestige of productive work

- Rebuild pathways into primary and secondary sectors

- Support youth mental health in the digital age

- Measure and regulate the attention economy as a labour force phenomenon

- Create structured, dignified alternatives that compete with the allure of digital fame

A generation cannot build a future from “likes” alone.

They need skills, structure, capacity, and purpose.

The long-term stability of nations depends on how clearly we see this — and how decisively we respond.