This is the first study of its kind in the field of Learning Organisation. It is also the first application of The Fifth Discipline on a national scale. It is a significant achievement not just for me but for the global community of practitioners at large.

We would be delighted to share insights into Systems Thinking as a research methodology. I am pioneering this approach for global application. My work focuses on developing structured frameworks for large-scale interventions. This aligns with Peter Senge’s advocacy for integrating Systems Thinking with robust data and research. This approach has gained recognition within the global SoL community. It highlights the need for more researchers. This need exists alongside government, business, and community leadership practitioners.

🎙️ KEY TALKING POINTS FOR PRESENTATION, INTERVIEWS OR PANEL DISCUSSIONS

🧭 1. Framing the Unemployment Crisis as a Systemic Design Problem

- Botswana’s high unemployment is not just an economic outcome—it’s a symptom of deeper systemic misalignment.

- The current system does not connect education, economic participation, and enterprise development effectively.

- We must change our focus. Instead of asking how to get people into jobs, we should ask how to build systems that produce jobs naturally. Instead of asking how to get people into jobs, we should ask how to build systems that produce jobs naturally.

⚖️ 2. Mismatch Between Economic Sectors and the Labor Market

- Too much focus on resource extraction (especially mining) with little trickle-down employment.

- Agriculture and manufacturing—sectors with job creation potential—are underdeveloped.

- A systems approach would focus on rebalancing these sectors to absorb both skilled and unskilled labor.

📚 3. The Education and Skills Pipeline is Disconnected

- There is a lack of alignment between the education system and real-world job demands.

- Few graduates emerge with the technical, entrepreneurial, or STEM-related skills needed to compete globally or innovate locally.

- Reform is needed to transform schools and tertiary institutions into centers of productivity and innovation.

🧑🏽🤝🧑🏾 4. The Role of Family Structure in STEM Capacity

- Restoring balance within households—especially through gender-balanced parenting—is critical to developing Botswana’s national capacity in STEM.

- The study finds that without strong foundational support at home, particularly for cognitive development in the hard sciences, broader reforms in education, employment, or economic policy are unlikely to achieve lasting success.

🧑🏽🤝🧑🏾 5. The Entrepreneurial Narrative is Overstretched

- While entrepreneurship is important, pushing everyone toward it often ignores structural barriers like:

- Lack of startup capital

- Weak value chains

- Low local demand

- We need to rebuild labor markets and firm ecosystems before individual entrepreneurship can thrive equitably.

🧠 6. Capacities, when adopted, Better Foster the New Economic System

- Society often sees employment as a government responsibility or a solo effort.

- Instead, build the tools that provide the capacity to interrupt automatic patterns in thinking and action, allowing for the shift of or growth of needed mindsets: citizens as productive co-creators of jobs for the unemployed, not just job seekers.

- This requires building family systems, business culture, and policy environments that reinforce productivity, collaboration, and dignity.

🌍 Calls to Action for Policymakers, Educators & Investors

- Foster ecosystems that connect STEM education, vocational training, and real sector development.

- Build regional food and manufacturing value chains that absorb labor and build export competitiveness.

- Create incentives for firms to hire, train, and keep local talent, not just automate or outsource.

WHAT ECONOMIC MODEL SUITS A SMALL NATION ASPIRING TO ACCELERATE ITS ECONOMIC AND POPULATION GROWTH?

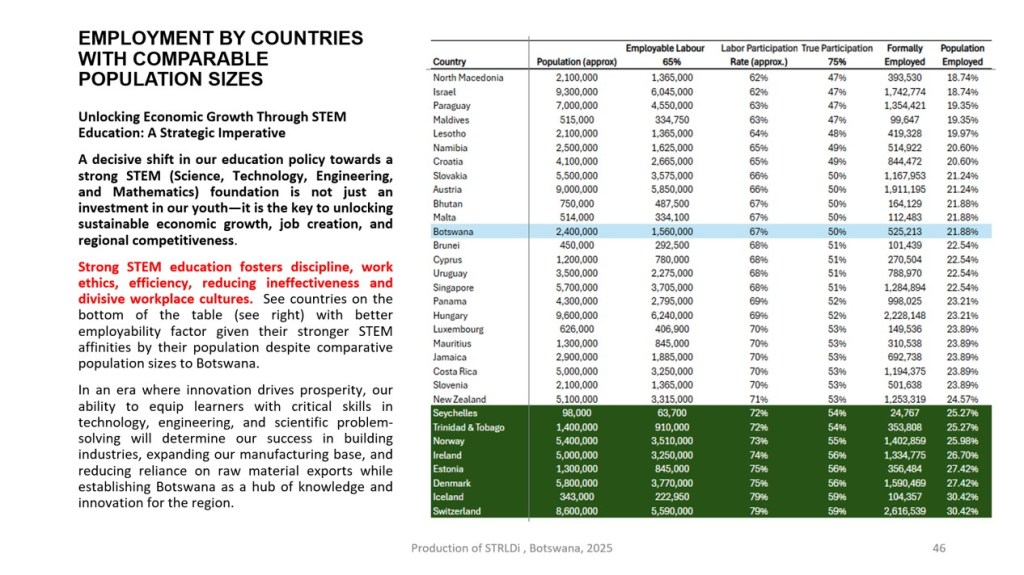

For a country with a stable but stagnant population (~2 million for 20 years) that now wants to accelerate economic and population growth to align with global ambitions, the most suitable economic model would be a Social Market Economy with Strategic Industrial Planning — supported by systems thinking principles.

INTRODUCTION TO PART 2

Part 1 of this article covered the next:

- Framing the Unemployment Crisis as a Systemic Design

- Mismatch between the Economic Sectors and the Labour Market

Part 2 will cover the next:

- Consideration of Socioeconomic Factors

- Pathways for Change and Empowerment

WHAT IS LIMITING THE GROWTH OF MANUFACTURING & AGRICULTURE ECONOMIC SECTORS IN BOTSWANA?

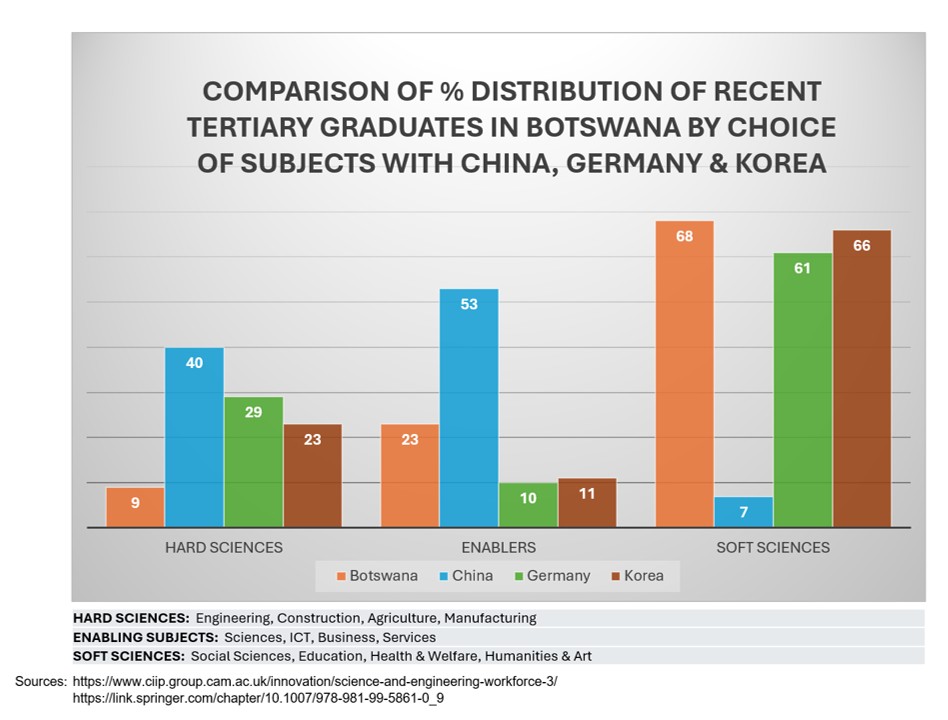

The emphasis on soft sciences in Botswana’s tertiary education system is disproportionate. This presents a structural challenge for economic diversification. It also hinders job creation. Fields like social sciences, business management, and education are valuable. However, the nation’s long-term economic sustainability depends on a well-balanced workforce. This workforce should include graduates in agriculture, manufacturing, and engineering. These sectors can absorb large numbers of workers. They also drive industrial growth. This imbalance limits the country’s ability to build strong value chains in food production, agro-processing, and manufacturing. This limitation reduces opportunities for large-scale employment. It also affects self-sufficiency.

For policymakers, economists, and business planners, urgent intervention is needed. They must realign education priorities with national development goals. Efforts should focus on incentivizing STEM-related fields and strengthening vocational training. Furthermore, fostering stronger linkages between industry and academia is essential. This will equip graduates with the skills required for a resilient and diversified economy.

The country’s slow transition towards producing more STEM graduates is influenced by several interwoven economic, social, and structural factors. First, historical educational trends and societal perceptions have reinforced the preference for humanities and social sciences. These fields are often perceived as more accessible. They are considered less challenging than STEM disciplines. Limited exposure to STEM career pathways has contributed to the skills gap. Inadequate early-stage STEM education and insufficient investment in technical training infrastructure have also played a role. Employers in STEM-related industries struggle to offer clear career advancement opportunities. This challenge arises from the skills mismatch. As a result, it discourages students from pursuing these fields. Furthermore, government policies and business strategies have yet to fully align. They need to create strong incentives such as scholarships, research grants, and guaranteed employment pathways. These incentives would make STEM careers more attractive.

Addressing these challenges requires a holistic approach. It involves integrating education reforms, workforce development, and economic policies. These policies emphasize STEM as a critical driver of national growth and innovation.

According to available data, a significant part of jobs require some level of STEM skills. Yet, the average proportion of STEM graduates directly employed in jobs that strictly need full STEM knowledge is around 30-60%. Many STEM graduates choose to work in non-STEM fields. This decision is influenced by job market demands and individual career choices. This means a major gap exists between the number of STEM graduates and jobs requiring a full STEM skill set.

KEY POINTS TO CONSIDER:

Variation by field:

The proportion of STEM graduates working in STEM-related jobs varies greatly depending on the specific STEM field. In some fields like computer science, a higher percentage of graduates are employed in directly related roles compared to others.

Skill mismatch:

Even when STEM graduates are employed in non-STEM jobs, they often utilize transferable skills. These skills include critical thinking, problem-solving, and analytical abilities. They acquire these through their STEM education.

Growing demand for STEM skills:

The overall demand for STEM skills is rising across various industries. This leads to a growing need for individuals with STEM knowledge. This need applies even in non-traditional STEM roles.

WHY THE SHIFT HAS NOT ALREADY HAPPENED

The slow transition toward producing more STEM graduates is deeply linked to existing family structures and childhood development conditions. These are explored further in the next segment.

This shift has supported the growth of white-collar jobs in sectors like health, education, and security. Yet, it poses challenges for industries like agriculture and manufacturing. These industries need to achieve economies of scale. They thus need strong skills in mathematics and science. The economy falls into a trap by distancing itself from these masculine industries and making them more profitable. Meanwhile, industries that do not rely on these skills, for example, nursing, teaching, or government work, continue to grow. Their success is less dependent on achieving a financial bottom line. This sets in motion a vicious cycle. It reinforces and justifies the persistence of the trend. The narrative suggests “we are much better off doing white-collar jobs, and that is where the money lies”.

Approximately 10% of graduates have skills in professional fields related to the sciences or applied sciences. About 6% are in engineering. About 7% are in the hard sciences. These figures represent the tertiary-educated population. They suggest that there are likely even more individuals in the broader population who lack the necessary hard science skills. These skills are required for sectors with a high demand for such knowledge, like agriculture and manufacturing. Data up to 2017 shows that the manufacturing sector has support from only 1% of tertiary students. These students have qualifications specific to manufacturing.

FAMILY STRUCTURE, STEM PERFORMANCE, AND SECTORAL IMPLICATIONS

Dependence on government assistance and absent fathers’ support can reinforce economic instability. This situation limits access to quality STEM education, mentorship, and extracurricular opportunities. As a result, children from such backgrounds focus on survival over long-term investment in STEM careers. Economists, government officials, and business planners need to tackle structural family dynamics. They can do this through targeted educational policies, community support programs, and economic incentives. These strategies are key to fostering a more STEM-oriented workforce.

The data indicate a growing trend of children being born into households without a resident male figure, with ex-nuptial births rising to over 84% in 2022 and projected to reach near-universal levels by 2030. This represents a profound shift in family structure, where mothers—often unsupported by partners—assume the full responsibility of child-rearing. Many of these mothers are themselves unemployed and reliant on social support or informal networks, which further compounds the vulnerability of the household. This dynamic has socio-educational implications for children, particularly in shaping their early exposure to diverse intellectual development influences.

As a result children raised in such households tend to perform better in soft disciplines such as social sciences, education, and healthcare (as the earlier graphs here show), but struggle to match their peers in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics) subjects. This pattern is linked to the absence of consistent male mentorship, which tends to play a formative role in developing a child’s abstract reasoning and spatial cognition—skills foundational to mastery in mathematics, physics, and technical fields. As STEM demands greater persistence and conceptual integration, children from single-parent households may face systemic disadvantages in accessing these domains, both cognitively and structurally.

This learning gap carries serious consequences for Botswana’s broader economic aspirations. The manufacturing and agriculture sectors—critical to national productivity—depend on a technically skilled workforce proficient in mathematics, science, and language. Without a strong STEM pipeline, these sectors remain underdeveloped, with low profitability and a limited base of competent talent to scale operations. If current trends persist, the absence of foundational male-led household balance will widen the STEM gap, constraining Botswana’s ability to build resilient, innovation-driven value chains in agriculture and manufacturing—further entrenching unemployment and economic fragility.

RESTORING BALANCE: REBUILDING FAMILY FOUNDATIONS TO STRENGTHEN NATIONAL RESILIENCE

To reverse the trend of growing male absence in households and its downstream effects on education and national productivity, national policy must shift from reactive punishment of gendered violence toward proactive systems that support healthy family formation and gender-balanced co-parenting. Families, communities, and institutions must be reoriented to treat fatherhood not merely as financial provision, but as an equally critical emotional and cognitive presence in the home.

Policies should focus on school-based and community-led programs that rebuild male identity around accountability, purpose, and interdependence—particularly in how boys learn to process emotions, resolve conflict, and lead without coercion. At the same time, national strategies must foster environments where young women are empowered to choose family partnerships from a position of strength and mutual respect, not economic desperation. Only through restoring dignity and functional roles for both genders within the household can Botswana shift the trajectory of family fragmentation and rebuild the foundational conditions for STEM learning, employment, and long-term national resilience.

SUMMARY OF DATA PRESENTED

Persistent unemployment is not just an economic challenge. It is a systemic issue reinforced by policy structures. Educational limitations and household dynamics also play a part. The lack of investment in STEM education (not just artisans) creates a self-perpetuating cycle. Industrial and technological sectors remain weak. This weakness limits job opportunities and economic growth. This structural loop keeps unemployment high. The workforce lacks the necessary skills to drive innovation and competitiveness. Additionally, economic dependence structures create further challenges. Households rely on government assistance and informal financial support. This reliance reduces incentives for skills development and entrepreneurship, thereby further entrenching joblessness.

For economists, government policymakers, and business planners, breaking this cycle requires targeted interventions. These include strategic investments in STEM education. Policies that promote job creation in high-tech industries are necessary. Additionally, reforms that encourage financial independence at the household level are important.

IDENTIFYING SYSTEMIC TRAPS IN EXISTING EMPLOYMENT SOLUTIONS

The strategies historically employed to enhance job creation have included attracting foreign investment. They have also relied on extractive industries and emphasized soft sciences. These approaches have inadvertently reinforced structural limitations within the economy. While these approaches generate short-term gains, they ultimately constrain broader economic diversification, negating much of the progress made.

The Repetition Trap

It is easy to fall into the habit of applying the same solutions repeatedly to complex problems. We often tackle symptoms (focusing on the tree) rather than understanding the underlying systemic structures (seeing the forest). Without a fundamental shift in perspective, these challenges will persist despite our best intentions.

The Structural Blind Spot Trap

We fail to recognize and analyze the deeper systemic dynamics. This leads to policies and interventions that reinforce existing constraints. It prevents dismantling them. By not addressing these foundational structures, we inadvertently navigate ourselves into the very challenges we seek to resolve.

The Employment Cycle Trap

A significant systemic challenge is the intergenerational cycle of unemployment. When parents, often sole breadwinner mothers, stay outside formal employment, their children are more to face the same fate. This perpetuates dependency and limits workforce participation, creating a recurring pattern that is difficult to break.

These lead to a crowding out of job hunters for jobs in the retails/services (tertiary retail) economic sectors and government. (Refer to pink and light blue portions of the pyramid above.) This limits the growth of secondary (manufacturing) and primary (raw material production) sectors. As a result, these sectors are virtually absent (LtG).

For each person who stays unemployed today, the loss per capita income per month is 5,848 pula. That is equivalent to 55,956 pula per annum per capita. This results in a staggering 5 billion loss to the population annually. Today, the per capita income per month is reduced to 1,650 pula. It should be growing to 16,550 pula, which would exceed South Africa’s 8,983 pula per month per capita.

The Hidden Structural Blind Spots of Building Synergistic Industries

A major challenge in many developing economies is the overwhelming reliance on imported goods. Most goods retailed locally are produced and manufactured outside the country. This practice drains financial resources. These resources could otherwise be reinvested to strengthen local industries. This continuous outflow of wealth erodes the economic foundation. It makes it difficult for citizens to build lasting financial security. Citizens also find it challenging to reinvest in local businesses.

Governments are aware of the need to expand agriculture. They also recognize the importance of manufacturing. These sectors have the potential to absorb the large unemployed population. This population is often estimated at around 60%. However, there is a lack of recognition of how the existing economic structure exacerbates this issue. Instead of fostering large-scale industry development, the market is fragmented into numerous small enterprises. Each enterprise competes against the other. They do this rather than collaborate. This competition prevents the formation of synergistic networks needed to establish resilient supply chains and industry-wide growth.

This dynamic is much like a generational cycle of conflict in relationships. When parents remain divided, their children grow up and continue the pattern. They live separate lives. Without intentional efforts to build trust and unity, the cycle persists across generations. Similarly, economies thrive when businesses and industries cultivate strong, long-term relationships—fostering collaboration rather than rivalry. By learning to develop and sustain productive partnerships, even among “strangers,” we can create a competitive foundation. This foundation will also be deeply interconnected and self-sustaining.

The Hidden Structural Blind Spots of Working with Infertile Lands

Countries struggling with infertile lands often fall into recurring structural blind spots. These blind spots shape their economic and agricultural choices. Over time, these choices accelerate land degradation rather than reverse it.

When land is infertile, the default response is often to prioritize livestock over crops. This logic holds: Livestock can endure harsher climates better than most crops. Nonetheless, as grazing depletes already sparse vegetation, the land loses its protective root systems, leading to soil erosion and desertification. A similar extraction-based mindset extends beyond agriculture. Industries focus on raw material extraction, like mining. Mining requires vast amounts of water for processing. This further depletes limited resources.

Another pattern emerges in production choices. Many of these countries invest heavily in breweries and alcohol production. This industry consumes ten liters of water to produce just one liter of beer. Meanwhile, long-term industrial growth remains elusive. Fear of betting too much on a single company stops companies from strategically developing. These businesses could eventually stand on their own. Instead, industries remain fragmented, hedging against economic disruptions but failing to build resilience.

Water scarcity further compounds these blind spots. In times of drought, horticulture—an industry that directly supports the water cycle—is often deprioritized. Instead, efforts shift towards planting warm-weather crops. These crops contribute to rising temperatures and erratic climate patterns. They are designed to withhold moisture and therefore do not support the Earth’s water cycle. Industries that can restore soil fertility are sidelined. These industries also stabilize local climates. This sidelining inadvertently reinforces cycles of environmental and economic decline.

What does this mean for profitability? Can industries built on these patterns sustain long-term growth, or are they caught in a self-perpetuating loop of diminishing returns? The data tells a compelling story—one that challenges us to rethink our approach to land, water, and economic resilience.

Understanding these traps is the first step toward breaking them. The next step is building strategies that foster sustainable, diversified economic growth and meaningful employment opportunities.

KEY POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

What then of building our economy? Our wealth creation strategies?

TO RELIEVE THE IMMEDIATE PAIN …

Export Unemployment:

The challenge of unemployment is deeply tied to a nation’s economic structure. Heavily importing manufactured goods and raw materials inadvertently exports job opportunities. For the population at large, this means fewer local industries and limited job creation, making self-sufficiency increasingly difficult. Economists must recognize the long-term impact of relying on external supply chains. This reliance drains financial resources. These resources have fueled domestic growth. Government leaders and policymakers need to change their strategies. They should focus on building robust agricultural and manufacturing sectors. Investments must drive local employment. This ensures that economic dependency is not reinforced. Business leaders and planners must rethink supply chains and foster collaborative industries that create sustainable employment opportunities. Addressing this imbalance involves more than just reducing unemployment. It also requires restructuring economies to be resilient. They need to be self-sustaining and capable of long-term growth.

Match Today’s Birth Rates with Tomorrow’s Employment Rates:

Unchecked population growth without a corresponding increase in job creation poses a significant economic challenge. For the general population, this means greater competition for limited employment opportunities, increasing financial insecurity. Economists must recognize that labor supply is primarily driven by birth rates. It is not mainly influenced by education. Therefore, workforce planning is a long-term effort. Governments must implement policies that align economic growth with demographic trends, ensuring that job creation keeps pace with population increases. Business leaders and planners play a crucial role. They foster industries that provide sustainable employment. They also invest in sectors that can absorb a growing workforce. The choices made today by families, policymakers, and business leaders will shape the employment landscape for future generations. Sustainable job creation must be at the heart of economic planning to prevent rising unemployment from becoming an unmanageable crisis.

TO TACKLE ECONOMIC CHALLENGES …

National & Community Dialogue as Families On Building Economic Sectors:

Economic growth is a collective responsibility, shaped by the choices we make as families, communities, and a nation. Avoiding short-term fixes in favor of sustainable solutions is essential for long-term stability.

We must break the cycle of misinformation. To achieve this, we need to move beyond a mindset focused solely on skill gaps. We must also tackle limited job creation. Instead, we need a clear national vision for growth. We must demand precise insights for informed decision-making. We should resist the temptation of short-term, ineffective solutions that have hindered progress. Moving forward, we must align education, skills development, and policy efforts to support industry expansion. We should actively join in shaping agriculture and manufacturing. Our goal is to build a future driven by opportunity, innovation, and self-reliance.

A nation’s economic and agricultural growth involves a shared responsibility. It requires collaboration between families and economists. Government officials and business leaders must also collaborate. For the general population, this means recognizing that individual choices impact national development. Active participation in industries such as agriculture and manufacturing can drive long-term prosperity. Economists must work to dispel misinformation, providing accurate insights that inform policies promoting sustainable job creation. Government leaders must align education, skills training, and policies with industry needs to ensure a workforce that meets market demands. Business leaders and planners can invest in innovation and local production. Doing so reduces reliance on external markets. It also fosters self-reliance. By shifting from passive observation to active participation, we can collectively build an economy driven by opportunity, innovation, and resilience.

Build Strong Agriculture & Manufacturing Links & Supply Chains:

Establishing a strong economic foundation requires a structured, proactive approach. This begins with understanding customer demand and complementary goods, assessing available and missing resources, and identifying critical supply chain processes. Collaboration with the private sector is essential. Together, they can co-develop a comprehensive economic roadmap. This roadmap aligns efforts and resources for national and regional competitiveness. By strengthening self-reliance while strategically integrating into global supply chains, economies can achieve sustainable growth. The ultimate goal is to build a resilient, high-value economy driven by informed decision-making and long-term strategic planning.

A resilient and high-value economy depends on the strength of its agricultural and manufacturing supply chains. This requires collective action from the population. Economists, government, and business leaders must also join. Citizens must recognize the power of informed consumer choices and local entrepreneurship in driving sustainable growth. Economists play a crucial role in assessing available resources, identifying supply chain gaps, and forecasting demand to guide strategic investment. Government leaders must align policies and infrastructure development to support competitiveness. They should guarantee collaboration between the public and private sectors. Business leaders and planners, in turn, must take a proactive approach to innovation, resource alignment, and integration into global markets. By working together, we can build a self-reliant, competitive economy that fosters long-term prosperity and resilience.

What does Building a Value-Creation Chain Look Like?

The value creation chain of sugar beet production spans from field to factory to by-products, involving multiple steps where economic, social, and environmental value is added. Here’s a structured view of the end-to-end value chain — often referred to as the sugar beet value creation system:

🌱 1. Input Supply

Value created: Enables farming; creates upstream business activity

| Components | Examples |

|---|---|

| Seeds | High-yield sugar beet varieties |

| Fertilizers | Nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium |

| Agrochemicals | Herbicides, pesticides |

| Equipment | Planters, cultivators, harvesters |

| Irrigation | Where needed (though beets are low-water crops) |

🚜 2. Cultivation (On-Farm Production)

Value created: Converts inputs into biomass and employment

| Activities | Notes |

|---|---|

| Land preparation | Tillage, soil testing, leveling |

| Planting and crop management | Weed and pest control, nutrient management |

| Harvesting | Mechanized lifting and cleaning |

| Employment and rural livelihoods | Labour and services around farms |

🏭 3. Transport and Logistics

Value created: Preserves value; connects farm to market

| Components | Notes |

|---|---|

| Beet transport to factories | Must be timely to avoid sugar degradation |

| Short-haul logistics contracts | Trucking businesses, fuel and maintenance sectors |

| Weighing and quality grading | Helps determine farmer payments |

🧪 4. Processing & Manufacturing

Value created: Transforms raw beet into sugar and by-products

| Processes | Output Products |

|---|---|

| Washing and slicing | Prepares for diffusion |

| Diffusion and purification | Raw juice → clarified juice |

| Crystallization | White granulated sugar |

| Drying and packaging | Final retail/industrial product |

| By-product extraction | Beet pulp, molasses, lime sludge |

🧃 5. Co-Product & Waste Valorization

Value created: Turns waste into revenue, energy, and soil health

| Co-Product | Use and Value |

|---|---|

| Beet pulp | Animal feed, compost, biogas |

| Molasses | Animal feed, ethanol, yeast, citric acid |

| Lime sludge | Soil amendment, construction filler |

| Process water recycling | Lowers environmental impact, reduces cost |

🛒 6. Marketing and Distribution

Value created: Converts product into revenue streams

| Channels | Examples |

|---|---|

| Retail and wholesale sugar sales | Supermarkets, food processors, bakeries |

| Industrial users | Beverage, candy, dairy, fermentation industries |

| Co-product buyers | Feed manufacturers, fertilizer producers |

💵 7. Revenue, Employment & Export Earnings

Value created: Direct and indirect economic growth

| Sectoral Value | Notes |

|---|---|

| Farmer incomes | Based on yield, sugar content, market price |

| Processor margins | From efficiency, co-product utilization |

| Rural employment | Farm labor, transport, factory operations |

| National economic contribution | Food security, tax base, reduced imports |

♻️ 8. Circular Economy & Sustainability Benefits

Value created: Environmental and long-term resilience

| Area | Example Benefits |

|---|---|

| Crop rotation | Supports sustainable farming (e.g., with cereals) |

| Soil carbon & health | Use of beet residues as soil conditioners |

| Climate mitigation | Less water use vs. sugarcane; potential for bioenergy |

| Industrial symbiosis | Energy recovery via biogas and co-location with ethanol plants |

Summary: Value Chain Nodes

Input Supply → Cultivation → Logistics → Processing → Co-product Valorization → Marketing & Sales → Economic/Environmental Gains

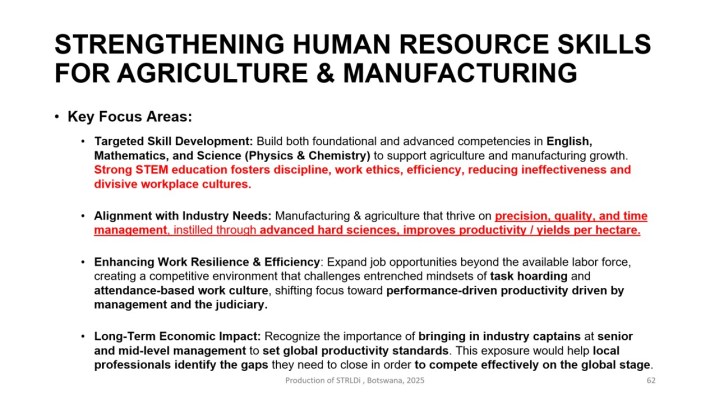

THE KEY: Strengthen Human Resource Skills for Agriculture & Manufacturing:

AT EDUCATION: Building a highly skilled workforce in agriculture and manufacturing requires a strong foundation in English, Mathematics, Technology, and Science. These subjects include Physics and Chemistry. This foundation enhances discipline. It promotes work ethics and efficiency. Additionally, it minimizes inefficiencies and divisive workplace cultures.

Why STEM—Especially Physics and Chemistry—Builds Disciplined, Efficient, and Harmonious Workplaces. The Hidden Power of STEM

The call to strengthen STEM education often centers on economic competitiveness and innovation. But beyond technical skill development, subjects like Physics and Chemistry cultivate a deeper, more transformative set of traits—ones that profoundly shape how people work, relate, and lead.

Physics and Chemistry demand a high level of precision and methodical thinking. They teach students to observe closely, reason logically, and follow through systematically. Every equation solved and every experiment conducted reinforces the habit of working in sequence, being detail-oriented, and respecting causality. These habits extend far beyond the classroom: they shape a mind that seeks accuracy, learns from failure, and values disciplined execution. In professional settings, this kind of thinking naturally reduces errors, promotes clarity, and strengthens overall operational efficiency.

Equally important, STEM subjects instill patience and sustained focus. Unlike subjects that may reward quick recall or subjective interpretation, mastering Physics and Chemistry takes time. The learning process often requires delayed gratification, tolerance for complexity, and a willingness to revisit and revise understanding. Through this, learners develop a strong internal work ethic—a quiet persistence that translates into dependability, responsibility, and endurance under pressure.

STEM education also reduces emotional reactivity and subjective bias. Because success in these subjects depends on evidence, not opinion, learners are trained to separate emotion from evaluation. They begin to value what works over what feels right, and results over rhetoric. In workplaces, this translates into less ego-driven conflict and fewer blame-oriented dynamics. Teams benefit from clearer thinking, more balanced problem-solving, and environments where feedback is accepted as a tool for growth—not as personal criticism.

Further, Physics and Chemistry naturally introduce systems thinking. These subjects are fundamentally about relationships—how variables interact, how structures behave under different conditions, and how small shifts can trigger cascading effects. By learning to think in terms of systems, students develop the capacity to understand complexity, anticipate unintended consequences, and work with interdependence in mind. This outlook is vital for organizations seeking coherence across departments, strategic alignment, and sustainable change.

From the Lab to the Boardroom: How Physics and Chemistry Shape Execution & Delivery

Finally, neuroscience research shows that sustained STEM learning strengthens executive function—the mental “command center” responsible for attention control, strategic planning, and self-regulation. These brain-level benefits support professional maturity, good judgment, and long-range thinking. Individuals become more reliable, more composed, and more capable of learning continuously—hallmarks of effective leadership and resilient organizational cultures.

In short, investing in Physics and Chemistry education is not only about producing scientists or engineers. It is about developing people with strong inner disciplines, who thrive in structure, respect facts, and build systems that work. These are the people who strengthen institutions, elevate teams, and carry the quiet force of transformation into every corner of public and professional life.

This section was added to the study report on August 2, 2025, following my reflections on Vice President Gaolathe’s briefing to private sector CEOs regarding the Botswana Economic Transformation Programme (BETP), in which he appealed to their willingness to invest in the country.

The following section here is a new addition to the study report, developed in response to the above session. It addresses a deeper truth behind the persistent national cry for execution and delivery—an urgency that, despite its volume over the years, has not produced sustained action. What we witnessed at the session was a clear signal: the real divide is not about willpower or laziness, but about structure. It was, in essence, a quiet standoff between the public and private sectors, each frustrated, each pulling in different directions.

The frustration, especially from the private sector, does not stem from apathy or resistance. It stems from being expected to deliver results while working within a system that has not been designed to support delivery. This is a classic case of putting the cart before the horse—and then expecting the horse to push it forward. But horses are not designed to push. Even the strongest of them will eventually tire and collapse.

This metaphor is more than symbolic. It speaks to the core systemic failure we are living through. The private sector has been expected to pull an economy that lacks the structural alignment to move forward. And the most critical misalignment? A workforce and leadership pipeline that has not been built on the necessary STEM foundation.

If the country as a whole—not just the government—were to put on its STEM skills shoes and pull up its socks, we would begin to see momentum. Not perfection, not immediate excellence in science and mathematics—but a foundational baseline of competence. We don’t need everyone to be scientists. But we do need at least 65% of our learning pathways grounded in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. Without it, we remain a nation demanding delivery without ever preparing for it.

This also explains our economic lethargy. It is what has kept us orbiting around extractive industries and a retail sector that depends almost entirely on goods produced more cheaply outside our borders. But if we were to change that baseline—shift the underlying structure—there is no reason Botswana cannot one day produce goods more competitively than South Africa.

This reflection is not merely an economic argument. It is an example of systems thinking reasoning, cutting across and advancing beyond classical economic logic. It’s not just about resources or incentives. It’s about redesigning the relationships and feedback loops that either enable or inhibit a nation’s capacity to deliver.

Once the private sector engages deeply with the study, there is every chance they will come to see their frustration in a new light. Not as a product of failure or bureaucracy, but as the natural consequence of a system misaligned from the start. And in that understanding lies the first real opportunity to move—together—toward change.

AT THE MINISTRIES: As Ministers of Agriculture and Manufacturing review the study, we believe they will advocate for a stronger focus on STEM. They will push the agenda ahead with the Ministry of Education. This includes attracting global talent of educators responsible for developing two generations of students, committed to reaching international standards. The next generation of teachers will emerge from these students, not from today’s educators. When a country’s political leadership sees the study, we are confident they will engage more effectively with communities. They will tackle the necessary shifts in families and education for STEM capacity building. This will be essential in strengthening the agriculture and manufacturing sectors.

AT THE WORKPLACE: Expanding job opportunities beyond the current labor force fosters a competitive environment. This shift focuses on moving away from rigid, attendance-based work cultures. Instead, it emphasizes performance-driven productivity led by effective management and judicial oversight.

AT ORGANIZATIONAL LEADERSHIP & JUDICIARY: The key to shifting from short-term personal gains is fostering a culture of collaboration. This leads to long-term organizational and national prosperity. Transparency and accountability are also essential. It also requires punitive measures for those who transgress these lines. De-glorify or reduce the radio noise on such transgressions. Strong leadership must align individual interests with collective goals, ensuring success is built on ethical practices and shared progress. By embracing continuous learning and systems thinking, we can move away from divisive workplace cultures. This shift leads us towards sustainable growth. Businesses thrive, communities prosper, and the nation as a whole benefits from a more stable and productive economy.

AT INDUSTRY: Aligning and demanding workforce competencies with industry needs—focusing on precision, quality, and time management—boosts productivity and agricultural yields.

In the industry: To achieve long-term economic growth, it is essential to attract experienced industry leaders. Integrating them into senior and mid-level management is also crucial. This will help set global productivity standards. It will also equip local professionals with the skills needed to compete internationally.

Building a highly skilled workforce in agriculture and manufacturing is essential for economic resilience and global competitiveness. This requires a collective effort from citizens. Economists, government, and business leaders must also contribute. The population must embrace STEM education to enhance discipline, efficiency, innovation, and, in particular, strong work ethics. Economists should analyze labor market trends and skill gaps to inform strategic workforce planning and economic policies. Government leaders must prioritize educational reforms, vocational training, and policies that align workforce competencies more strictly with industry needs. Business leaders and planners must drive a performance-based culture, investing in leadership development and productivity standards to compete globally. A well-prepared workforce ensures increased productivity, economic stability, and long-term growth.

Build to Sustain A Strong, Self-Resilient Economy:

Botswana is uniquely positioned to expand its manufacturing sector by strategically plugging into unmet regional demand—especially in SADC and broader Southern Africa, where intra-regional trade is still below potential. The key lies in focusing on import substitution, value chain gaps, and high-demand regional goods that are currently being imported into neighbouring countries from outside Africa.

Here are priority areas of manufacturing where Botswana can expand:

🏗️ 1. Agro-Processing and Food Manufacturing

Botswana imports and exports raw agricultural produce with minimal local processing. Regional demand is high for processed and packaged foods:

- Canned and frozen vegetables & fruits

- Milled grain products (maize meal, wheat flour, sorghum meal)

- Dairy processing (long-life milk, yoghurt, cheese)

- Meat processing (sausages, canned beef, biltong, pet food)

- Juices, sauces, edible oils

- Animal feed production

🔁 Why it matters: Most SADC countries import these from outside the region (e.g., South Africa, Europe, Brazil), yet the region has the raw produce.

🧼 2. Essential Consumer Goods

Low-to-mid tech manufacturing of everyday goods is still underdeveloped in Botswana, but demand is huge in neighbouring countries:

- Soap and detergent production

- Toothpaste and personal care products

- Sanitary pads, diapers, hygiene products

- School supplies (pens, paper, exercise books)

🔁 Why it matters: These products are still largely imported by many African countries. Producing them in Botswana can fill a cost and logistics gap regionally.

🧵 3. Textiles and Garments

Though previously attempted, Botswana can revive this sector with a regional focus and affordable basic garments:

- School uniforms, workwear, hospital linen

- Low-cost undergarments, socks, cotton basics

- Canvas and industrial textile items (e.g. bags, tents, tarpaulins)

🔁 Why it matters: Countries like Zimbabwe, DRC, and Malawi all import basic garments, often from China and India.

🧱 4. Construction Materials

SADC’s infrastructure boom creates demand for durable, standardized building materials:

- Roof sheeting, bricks, cement, tiles

- Steel fabrication (gates, windows, frames)

- Precast concrete and modular components

- Paints and adhesives

🔁 Why it matters: Many of these are bulky and costly to transport from far. Botswana’s proximity to central and western SADC makes it competitive if scaled.

💊 5. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Consumables

With regional shortages and lessons from COVID, Botswana can localise and regionalise:

- Basic generic medicines

- Medical gloves, masks, bandages, swabs

- Veterinary pharmaceuticals

🔁 Why it matters: Many SADC countries import 70–90% of medical consumables. Botswana can become a clean, trusted manufacturing base.

⚙️ 6. Automotive and Machinery Assembly

With some policy support and skills development:

- Agricultural equipment assembly (e.g., planters, threshers, irrigation kits)

- Vehicle spare parts and kits

- Workshop tools and metal components

🔁 Why it matters: Smallholder farming and mining sectors across the region rely on imported equipment.

🔌 7. Packaging Materials

All manufactured goods need packaging:

- Plastic bottles, jerry cans, buckets

- Bio-degradable packaging materials

- Corrugated cardboard boxes

- Labels, cartons, paper bags

🔁 Why it matters: Regional producers (including in Zambia, Zimbabwe, and Malawi) often import packaging from South Africa or overseas.

✅ Strategy to Plug In

To expand into these areas, Botswana can:

- Set up industrial clusters near existing agricultural or trade routes (e.g., Lobatse, Francistown, Palapye)

- Attract anchor firms through public-private partnerships and local procurement incentives

- Use SACU and SADC trade agreements to target captive regional markets

- Strengthen skills development and logistics infrastructure

- Align with AfCFTA for long-term continental market expansion

Shifting from resource extraction to resource production and an employment-driven economy in agriculture and manufacturing is a multifaceted process. It requires creating a strategic balance between job creation. There is also a need for the adoption of ICT and automation. While ICT enhances efficiency, it does not primarily drive employment. It often leads to job displacement rather than creation.

Building a competitive workforce, particularly in manufacturing and agriculture sectors, requires prioritizing STEM education and hard science skills as essential.

Strengthening horticulture production, in particular, for climate resilience, and advancing manufacturing will boost yields beyond global standards. This is supported by improved soil health. Climate adaptation and workforce productivity also contribute.

Sustainable economic growth depends on strong industry leadership. It involves attracting regional and global experts to drive investment. Additionally, it requires incentivizing and training local leaders through international exposure and development programs. Also, engaging households is critical. Involving the education sector is essential for nurturing future industry leaders. Job creation is ultimately driven by leadership, not STEM graduates alone.

Policymakers, economists, and business leaders must collaborate to build a workforce that meets global standards. They must also create sustainable employment opportunities. Industry captains, not graduates alone, are the key to job creation and economic transformation.

🔗 SEE THE BIGGER PICTURE: WHY UNEMPLOYMENT FUELS A CULTURE OF SILENCE

Understanding unemployment in Botswana isn’t just about statistics—it’s about how economic exclusion shapes societal behaviors, values, and power dynamics. People without access to stable jobs often struggle. They lack skills, pathways, or dignified income. As a result, they become entangled in informal or corrupt systems and crime to survive.

In a related reflection, When the Community Speaks: Corruption, I explore how a silent societal order emerges in response. People choose not to speak out. They are not indifferent. The risks of rejection, poverty, or retaliation are too high. Corruption, in this sense, is not just an ethical issue. It is a systemic response to economic precarity. This precarity is a state of persistent insecurity about employment or income.

This connection highlights the need to design economic systems that empower rather than expose. These systems should allow people to resist corruption without risking their survival.

👉 Read the companion reflection: When the Community Speaks: Corruption

Together, these reflections argue for one thing:

To solve unemployment is to weaken the roots of corruption. System redesign must start there.

Perfect—here’s a polished blog section (which you can also adapt into a LinkedIn carousel or visual thread) that unpacks the entrepreneurship narrative in Africa, aligns it with your framing, and gives it a professional, systems-thinking lens:

🛠️ RETHINKING THE ENTREPRENEURSHOP NARRATIVE IN AFRICA

Across the continent, a powerful message echoes through policy briefs, social media, and donor programs: “Be your own boss. Become an entrepreneur.” This vision of self-made success resonates with many. Yet, it also masks deeper structural challenges. Additionally, there are expectations placed on individuals.

🌍 Why the Push for Entrepreneurship?

Africa’s youth bulge is colliding with stagnant job markets. Formal employment systems can no longer absorb the volume of school leavers, graduates, and retrenched workers. In response, entrepreneurship is being promoted as the main pathway to survival, mobility, and dignity.

This narrative has taken root for several reasons:

- Structural unemployment: Formal sectors are underdeveloped or shrinking, leaving millions without sustainable work options.

- Donor and policy pressure: International development agendas view entrepreneurship as scalable, low-cost, and empowering, particularly for women and youth.

- Cultural familiarity: Informal trade, side hustles, and family enterprises have long been part of African livelihoods. Entrepreneurship is not foreign; it’s often default.

- Emotional appeal: The message speaks to pride, independence, and the promise of self-determination.

But what happens when this narrative becomes the only solution?

⚠️ A Narrative With Limits

Not everyone is meant to be an entrepreneur. And not everyone should be. Overemphasizing this route without addressing structural barriers does the next:

- Shifts responsibility from systems to individuals

- Underplays education, infrastructure, and capital gaps

- Glosses over failure as a systemic outcome, not personal inadequacy

When entrepreneurship becomes a substitute for employment policy or industrial development, it becomes a trap dressed as empowerment.

✅ A Systems-Based Alternative

We must build sectors like agriculture and manufacturing on a robust education system. This foundation is crucial to truly unlock their potential. This system should prioritize STEM, technical training, and innovation. This must be supported by co-led, resilient family systems. In these systems, both men and women contribute to shaping individuals as productive assets. These individuals are capable of becoming entrepreneurs and investors. They generate margins that fuel business growth and future employment.

This perspective doesn’t reject entrepreneurship, but grounds it in a more realistic, inclusive, and regenerative model. One where entrepreneurship is part of a wider ecosystem, not a replacement for it.

THE REAL WORK AHEAD

We must reframe entrepreneurship as a choice within a functioning system, not a forced path out of crisis. This means:

- Investing in science application / technical education and innovation infrastructure

- Strengthening local value chains in agriculture and manufacturing

- Fostering socially anchored business models that share risk and value

The goal is not to turn everyone into a startup founder. It’s to build systems where everyone can contribute meaningfully—and thrive.

Further Notes:

Watch my presentation of the study given at the 50th anniversary of The Inner Game of Tennis Conference. Here is the video of Sheila’s presentation on The Inner Game Conference 2024. The presentation is titled: “Systems Thinking, sometimes called the Doom Discipline.” It also explores why the Inner Game Practices will replace the doom with hope. I emphasize that the toughest solutions still need both leaders and citizens to work on their inner game. They need to focus on mental models and personal mastery. Leaders and citizens must see eye-to-eye for real hope for progress.

BOTSWANA NATIONAL POLICY HACK:

WHY?

- In 2011, the country created and had (retained) 611K jobs (60% of the working-age population)

- In 2017, the number of formally employed is about 400K, the majority are in the government and retail sectors

- The economy is not supported but remains suspended and so leads individuals to turn to trade and entrepreneurship yet are unable to support themselves without government support (see diagram above)

- The loss per capita income per month when 60% of the working-age persons stay unemployed is 6K pula (per month)

- The loss of GDP (per annum) 5B pula

WHAT?

- Building of broad-based economy that is not suspended but supported.

- The widest part of the pyramid absorbs the greatest portion of a nation’s employment. The sectors at the apex are the narrowest.

When corporations grow, jobs grow, and not without it happens without fail. And then wealth grows. Start-up companies are like seedlings and need to be nurtured before they can sustain people. Too much feeding will also cripple it. They should start slower so that the roots grow and anchor securely within the market. Only then can the tree become huge and skilled enough to produce more food and fruits for everyone.

STOP: Thinking of putting food on my table. And my survival.

Creating jobs is a consequence/result of the above, not the focus.

Companies are meant to create wealth for me.

START: Thinking of putting food on everyone’s table.

VISION: Prosperity for all.

- To the extent, that biological families stay intact

- To the extent the young master their STEM, particularly English, Mathematics, and Science (EMS).

- To the extent, the economy develops captains of industries in the agriculture and manufacturing sectors of the nation’s economy

HOW?

- Every member of the nation plays an active role voluntarily

- Messages passed on by role plays, cartoons, media stories

- Allow the member countries in SADC to appreciate the opportunity cost of large numbers of unemployed persons within the region. Each year, 70% of the working-age population not employed formally results in a 5B loss to the nation’s economy. This amounts to 6k per capita per month.

- Determine a full list of goods and services that can be provided to the world. Build a matrixed goods supply chain as a region. Base it on goods demanded in the region. These goods should also be exported to the continent and the world. Determine how Botswana fits in. Assess the efficacy of the service. Consider the economies of scale that create margins. These margins lead to the growth of corporations and jobs.

WHO?

Dialogue on understanding the results by:

- The Nation

- The Kgotla, Chiefs & VDCs

- The media

- The Community

- The intact family – both parents who bore children – no coercion – just sharing the picture and hopes

WHEN?

Like Yesterday?

OTHERS?

🧩 Optional Link:

“We must first redesign the economy. This will make employment possible, desirable, and dignified. Only then can we effectively fight corruption and social instability.”