Here is a draft policy statement for the National Agriculture Sector Policy for Botswana. It is grounded in the core themes here:

Policy Statement: National Agriculture Sector Policy – Republic of Botswana

That Botswana commits to developing a regenerative, market-aligned agriculture sector that ensures food sovereignty, inclusive growth, and climate resilience.

The Government of Botswana affirms that agriculture is a cornerstone of national development, food sovereignty, economic diversification, and environmental stewardship. The policy recognizes the sector’s current contribution of less than 2% to GDP. It commits to restoring agriculture as a central driver of the economy to what it was pre-Independence. The target is a progressive increase toward a 30% contribution over the next decade. In response to persistent rural poverty, this policy sets a bold and coordinated course. It aims to create industry leaders. The intention is to create formal employment for 800,000 persons in the industry in the next five years. It addresses growing food demand and increasing climate variability. The goal is an inclusive, sustainable transformation of the sector. At its core is the commitment to secure resilient livelihoods and long-term national food security.

Methodology:

This is our attempt to map the value chains for both plant and animal production. We aim to highlight their potential when more deliberately integrated into manufacturing and export. Such integration could significantly expand the scope of agricultural production in the country. We developed these value chains based on recommendations in the unemployment study. This process identified the national production systems for plants and animals. This identification helped define what the policy needs to include.

We recognize that the past decades have shown that fragmented, supply-driven models of agricultural development are insufficient. They cannot build a resilient and self-sustaining agricultural sector. These models are often isolated from market realities, ecological dynamics, and the lived experiences of producers.

Therefore, this direction is built on the following foundational commitments:

1. National Planning and Coordination:

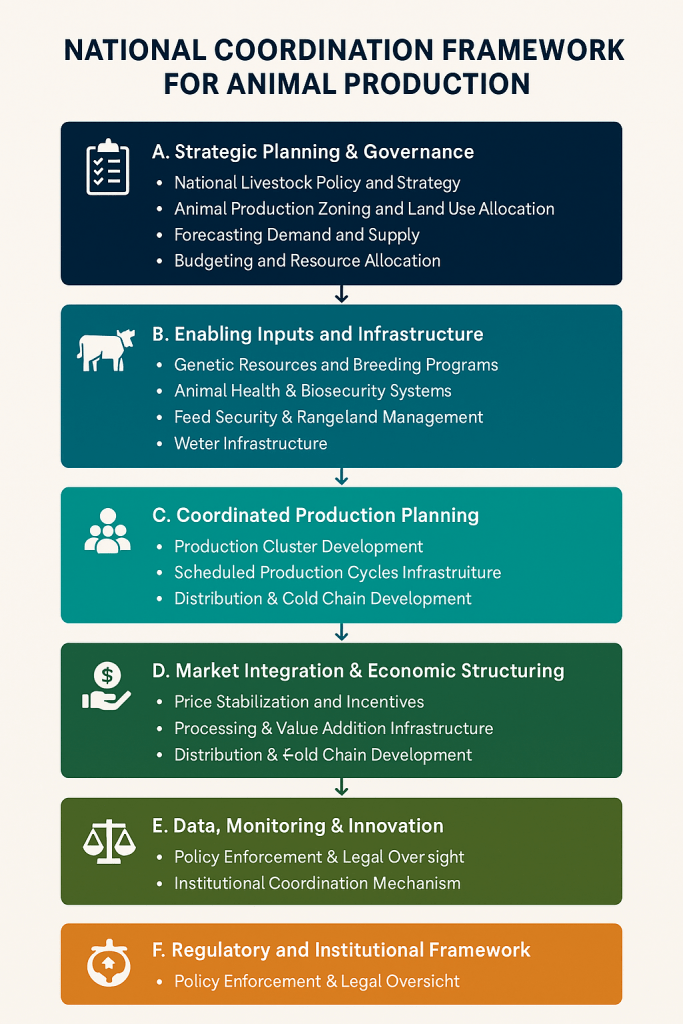

Establish a central, data-driven national agricultural coordination system. It will synchronize planning across input supply, production, logistics, processing, and markets. This system will guide seasonal priorities, production quotas, investment, and climate-resilient land use planning across regions.

2 Producer-Led, Market-Aligned Development:

Enable and empower producers. Both small- and large-scale producers should be able to respond predictably and profitably to national and regional market demands. This includes reorienting support structures, training, subsidies, and infrastructure toward farmer-managed, demand-sensitive production systems.

3. Agroecological and Regenerative Approaches:

Transition from extractive, mono-crop models to diversified, regenerative agricultural systems. These systems restore soil health and recycle biomass. They also retain water and contribute to climate stability. This approach will be prioritized especially for horticulture, fodder, and small livestock systems.

4. Strategic Investment in High-Impact Value Chains:

Prioritize value chains with strong domestic consumption. Scale those that have export competitiveness potential. They should also enhance rural employment, such as potatoes, garlic, poultry, fodder crops, and integrated livestock-crop systems.

5. Integrated Farmer Training and Knowledge Ecosystem:

Institutionalize farmer learning hubs. These hubs deliver applied, experiential knowledge rooted in regenerative practices. They focus on market access strategies and agribusiness management. This ensures producers evolve as innovators and decision-makers in the sector.

6. Equity and Inclusive Participation:

Encourage gender inclusion in agricultural policy design. Promote youth participation in land access and financing. Include both in the value chain participation. These actions aim to foster inter-generational equity. They also support economic resilience and promote innovation.

7. Resilient Infrastructure and Climate Adaptation:

Prioritize investment in irrigation, cold storage, and feeder roads. Focus on renewable energy and digital platforms. These investments reduce losses and enable year-round production. They also buffer rural communities from climate-related shocks.

8. Evidence-Based Policy and Governance:

Develop and maintain long-term, spatially disaggregated data systems. These systems should cover rainfall, production trends, consumption patterns, and market behaviors. This approach enables responsive governance and informed policy-making.

Through this policy, Botswana aspires to build a resilient, regenerative, and inclusive agriculture system. This system feeds the nation. It sustains its landscapes. It uplifts its people and contributes to regional food security.

I. CROP PRODUCTION (ALL PLANT PRODUCTS)

AGRICULTURE PLANT PRODUCTION VALUE-CHAIN

II. ANIMAL PRODUCTION (ALL ANIMAL PRODUCTS)

AGRICULTURE ANIMAL PRODUCTION VALUE-CHAIN

Here are my general observations:

Observations on the Tone of the Policy Document

Observations on the Tone of the Policy Document

The overall tone of the policy document reflects a strong sensitivity to public and political concerns. This sensitivity is understandable given its context. These include:

- The voices of the unemployed, which underpin references to income inequality and social inclusion. This often implicitly centres on women (framed through social justice) and youth (highlighted through a focus on technology), and graduates. The latter assumes that graduates create jobs. Unless they are organizational or industry leaders, they are unlikely to create jobs. However, they need to grow their jobs so as to keep them.

- The perspectives of environmental advocates, whose concerns are reflected in the emphasis on sustainability and ecological resilience.

- It is imperative to align with legacy national commitments, such as Vision 2036. Additionally, alignment with broader international frameworks, such as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), is necessary.

A Cautionary Note

These policy commitments are important. However, they often prioritize short-term visibility. This comes at the expense of the long-term national institutional requirements for effective planning, coordination, production, and monitoring. These foundational systems require time and technical expertise. They also need iterative refinement. These elements are frequently sidelined in favour of more politically resonant themes.

Critically, placing agriculture as a business at the center of policy design is essential. Over time, this strategy would address many of the concerns raised above. This approach would expand employment. It would generate income and drive sustainability through economic participation.

Still, the voices of producers and agri-business practitioners face a disconnect. They are deeply focused on day-to-day operations. There may be a gap between policy narratives driven by public and political concerns. The realities of running productive, competitive enterprises may differ from these narratives. Their limited time and attention are spent on execution, not engagement. We risk not meeting the industry’s needs to operate effectively and grow. This is crucial for building a future for agriculture tomorrow.

Summary of Gaps Not Yet Covered in Policy Statement

The following areas from the National Matrix are not explicitly or adequately addressed in the current policy statement draft and should be considered for integration:

1. Demand-driven Centralized Production Planning

2. STEM capability and national education agenda

3. Explicit and Comprehensive Coverage of Input Supply Industries that mirrors the national matrix structure (e.g., seed systems, irrigation suppliers, agrochemicals)

4. Position on drought-resistant crops and climate re-balancing through non-drought crops (particularly horticulture products)

5. Detailed Distribution & Logistics Chain

6. Retail price control and market fairness

7. Clear Export Strategy and Infrastructure

8. Defined Roles of Governance and Institutions (planning units, coordinating bodies)

9. Financial Architecture (agricultural credit, risk financing, guarantees)

10. Land Use and Tenure Security

11. Monitoring & Evaluation Frameworks with Data Systems

12. Processing/Agro-Industrial Zones Strategy

Next Steps / Recommendations

- PRIORITY: Expand the policy statement into a full policy framework that mirrors the national matrix structure.

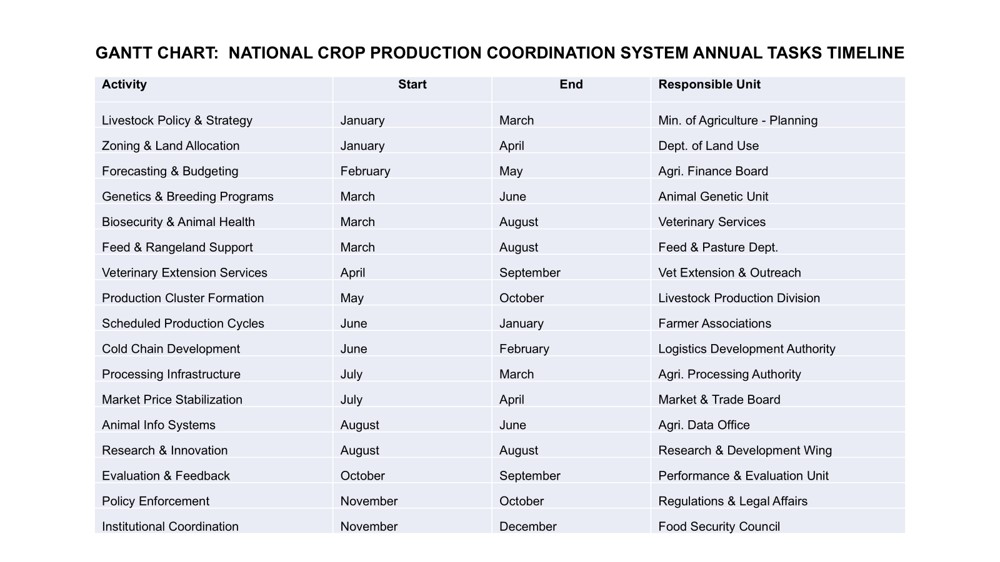

- FOLLOW-THROUGH: Develop annexes or implementation frameworks with Gantt charts, institutional roles, and sector-specific targets.

- Consider linking the Policy Statement to investment promotion, especially to catalyze private sector participation.

- Develop a Monitoring & Learning Plan that operationalizes the longitudinal data philosophy embedded in your matrix.

Warm regards,

Ms Sheila Damodaran

Managing Director

Systems Thinking Research & Leadership Development Institute (STRLDi)

Endnotes:

Here’s a breakdown to help clarify the differences between a policy statement, a strategy or planning document, and vision/goals:

1. What is a Policy Statement?

A policy statement is a high-level declaration of government or institutional intent. It captures principles, priorities, and commitments to guide future decision-making and action in a sector like agriculture.

Features:

- Broad in scope

- Sets the direction, not the exact route

- Framed in normative language (“we commit to…”, “we shall…”)

- Establishes what is important and why

- Often endorsed at the political or executive level

Example from agriculture:

“Botswana commits to developing a regenerative, market-aligned agriculture sector that ensures food sovereignty, inclusive growth, and climate resilience.”

Think of it as:

The compass: it tells you where north is, but not how to get there step-by-step.

2. What is a Strategy or Planning Document?

A strategy or planning document translates policy into operational pathways. It outlines the how, who, when, and with what resources.

Features:

- Breaks the policy into objectives, outputs, and activities

- Includes targets, timelines, budgets, and responsibilities

- Often supported by monitoring frameworks and implementation roadmaps

- May be revised periodically (e.g., every 5 years)

Example:

A National Horticulture Development Plan with targets to expand irrigated land by 10,000 ha over five years, led by the Ministry of Agriculture.

Think of it as:

The roadmap and the vehicle maintenance manual: it tells you how to make the journey and what each actor must do.

3. Is it the same as Vision or Goals?

Not quite, though it overlaps.

✔ Vision Statement:

- A vision is an aspirational future — the “north star”

- Short, emotionally resonant, and time-insensitive

- E.g., “A food-secure Botswana with thriving rural economies.”

✔ Goals:

- Measurable, specific targets derived from the policy

- Sits between policy and strategy

- E.g., “Reduce agricultural imports by 40% within 5 years”

🟨 Summary of Differences

| Element | Policy Statement | Strategy/Plan Document | Vision / Goals |

|---|---|---|---|

| Purpose | Set direction & principles | Define implementation pathways | Inspire / define end destination |

| Timeframe | Long-term, enduring | Medium-term (e.g., 5 years) | Long-term aspiration |

| Level of Detail | High-level | Specific and operational | High-level for vision; mid-level for goals |

| Tone | Declarative, normative | Instructional, structured | Inspirational (vision); action-driven (goals) |

| Audience | Public, lawmakers, funders | Implementers, civil servants, donors | Public, internal teams, stakeholders |

Why You Need All Three

A strong policy statement:

- Anchors and legitimizes future strategies

- Clarifies why and what the country stands for

- Builds coherence across ministries, donors, and local actors

But without a strategy, the policy remains only a declaration.

And without a vision and goals, people don’t know what success looks like.

Given the challenges of land access and capital availability for a young graduate from BUAN (Botswana University of Agriculture and Natural Resources), a potential career path can still be designed to eventually enable the graduate to own their own land and enterprise. This career path would need to focus on building skills, networks, and capital while navigating the systemic challenges of land access. Here’s a strategic plan that can be adopted:

1. Start with Employment in Agri-Business or Agribusiness Consulting

Short-Term Strategy (1-5 years):

2. Pursue Agribusiness Entrepreneurship through Off-Farm Ventures

Mid-Term Strategy (3-10 years):

3. Leverage Government and Private Sector Initiatives for Land Access

Medium-Term Strategy (5-10 years):

4. Invest in Agricultural Education and Skill Transfer

Ongoing Strategy:

5. Eventually Own Land and Scale Your Business

Long-Term Strategy (10+ years):

Conclusion:

For a young graduate from BUAN facing challenges in accessing land and capital, the path to eventually owning a farm and enterprise may seem daunting, but it is not impossible. By starting with small-scale ventures, gaining practical experience, and focusing on business-building, they can develop the necessary skills, knowledge, and capital to one day purchase land and build a successful agricultural enterprise. The strategy involves a combination of employment, entrepreneurship, and seeking government/private sector support for land access, with a long-term focus on growth, education, and networking.

LikeLike