In his LinkedIn post, Hendrik Wierenga argues that corruption doesn’t originate in politics or boardrooms. Instead, it begins when society shifts its values. Society starts to favor success over integrity. He emphasizes that when societal condemnation and legal repercussions diminish, individuals are more likely to engage in unethical behavior. The fear of social and legal consequences is a key deterrent. Wierenga concludes that corruption thrives not only due to flawed systems. It also prevails because of societal indifference. He highlights that the decay of ethical standards is a cultural failure and a legal one.

I found Hendrik Wierenga’s perspective on the roots of corruption particularly compelling. He especially emphasized the quiet, yet powerful, role that indifference plays in our society.

Taking a stand against indifference isn’t easy. It demands courage, because challenging it often means confronting an unspoken societal order—one that discourages dissent and quietly enforces conformity. To go against it is to risk social exclusion, condemnation, or worse, economic hardship or total disarray. And for those who’ve faced these consequences before, the fear of returning to them is real. So, many choose silence. Most simply comply.

This silent societal order persists for one reason: survival. It offers protection—protection from rejection, from poverty, even from death. It is guarded fiercely and rarely acknowledged. We don’t name it. We don’t confront it. Instead, we shift our focus to the visible structures built to fight corruption—the institutions, the legal frameworks, the public arrests. Once someone is caught, resources respond swiftly, and society is comforted.

But what exactly is this order? It is a fusion of cultural norms and institutional silence. It thrives in the unspoken. It is the whispered advice: “Don’t get involved.” It’s the societal shrug when someone clearly undeserving wins a contract. It’s the silence in boardrooms, classrooms, and dinner tables. Accountability is quietly pushed aside at these places. This happens because of fear of isolation, loss, or retaliation.

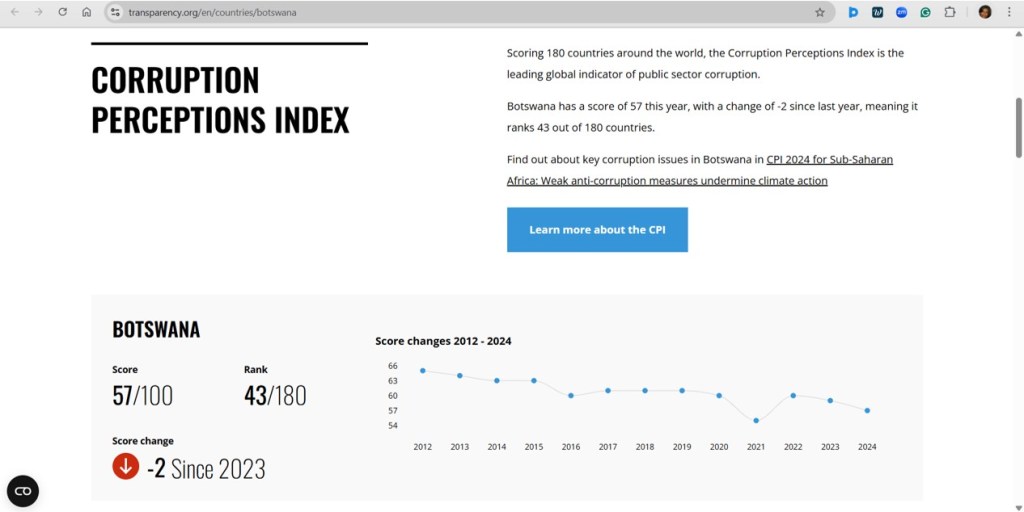

We’ve seen it unfold across regions. In South Africa, the Zondo Commission revealed how an entire machinery of government was hijacked. This was not only through political complicity but also through civil servants who stayed silent. They remained quiet for years, fearing dismissal or worse. In Kenya, the term tenderpreneur has become part of everyday language. It indicates a new norm where survival often depends not on education or merit but on who you know. Those who challenge this order are sidelined, blacklisted, or shamed into submission. Even in Botswana, where institutions are often praised for their integrity, whistleblowers face social pressure. They also face professional and legal pressure to protect the status quo.

The point is this: the silent order is not passive; it is alive. It shapes who gets to speak, who gets to rise, and who learns to keep their head down. It’s why many stay quiet, even when they know what is right. Confronting the network can come at a price no one wants to pay again.

The Systemic Roots of Indifference

Indifference is often dismissed as personal apathy. But in truth, it is far more than that. It is a systemic adaptation. It forms a quiet resistance that emerges when communities are caught in cycles of disillusionment, powerlessness, and fear. This silence is not accidental; it is taught, reinforced, and passed on.

The Origins of Indifference

1. Historical Disenfranchisement

Many communities carry the weight of historical exclusion—from governance, from land, from opportunity. Over time, people who have been repeatedly ignored or punished for speaking out learn that silence is safer than action. Indifference, in this light, is not laziness—it is a learned survival strategy.

2. Erosion of Trust in Institutions

Corruption scandals go unpunished. Whistleblowers are persecuted. Leadership speaks of reform but delivers little. These realities create what systems thinkers call a broken feedback loop. When no visible change follows courageous action, it teaches its citizens: “It’s not worth it.”

3. Fear of Retaliation

In systems where opportunity is mediated through personal networks or political loyalty, dissent becomes dangerous. Losing a job, being denied services, or social exclusion are not abstract fears—they are real consequences many have already faced. Silence, then, becomes the rational choice.

How Indifference Shapes Community Dynamics

Indifference is not a static emotion. It shapes the behaviors, relationships, and future of a community. When it becomes widespread, it produces three major consequences:

1. Breakdown of Social Trust

If everyone expects everyone else to stay quiet, collective action becomes nearly impossible. A form of coordination failure emerges, where no one acts because no one else is acting.

2. Normalization of Corruption

Over time, communities start to adapt to corruption, not challenge it. Bribes become “shortcuts.” Tenderpreneurship becomes “strategy.” Small infractions feel necessary for daily survival. And so, it continues.

3. Collapse of Collective Agency

Repeated failures to create change slowly erode hope. Communities stop believing that transformation is possible. Fewer people speak up. Fewer listen. Fewer act. It, now running on silence, reinforces itself.

The Deeper Truth: Indifference is Designed

In systems thinking, indifference is not an individual flaw. It is a product of system design.

To tackle it, we must go beyond naming corruption. We must design systems that:

- Rebuild trust in feedback loops, where action leads to consequence.

- Reduce the personal cost of integrity, making it safer to speak;

- Allow meaningful participation, so communities feel they shape their own future.

Until then, silence will stay the safest choice. And indifference, the most rational response.

Here is your blog-styled post, formatted for your voice and audience:

When Corruption Feeds on Inequality: The Hidden Costs of Socioeconomic Disparities

In our efforts to understand corruption, we often ask, “Why do people tolerate it?” or “Why does it persist despite reforms?” But the answer isn’t always about law or leadership. Sometimes, it’s about survival.

When we look closely at the ground realities, we see families trying to secure food. Young people are desperate for work. Communities are also excluded from systems of justice. We begin to see a different truth: corruption often thrives not just because of greed, but because of inequality.

Economic Pressures: When Ethics Collide with Survival

In contexts of poverty or extreme unemployment, individuals often find themselves forced into ethical compromises. A bribe for a health certificate. A “cut” for someone processing a job application. A look the other way when funds disappear. These are not always acts of moral weakness—but adaptations to a system that offers little room for honest progress.

According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), youth unemployment in sub-Saharan Africa remains the highest in the world. Over 70% of young people work in informal or “vulnerable” jobs. In such an environment, corruption becomes the price of access—not the exception, but the norm.

It is not that people support corruption. It is that in some systems, resisting corruption comes at a higher cost than tolerating it.

Access to Resources: The Unequal Armor Against Corruption

Indifference to corruption doesn’t start in adulthood. It is cultivated early through uneven access to education, work, and justice. When some groups are consistently left out, they stop believing the framework can be fixed. Or worse, they begin to believe the structure was never meant for them.

1. Education

Quality education equips people with both knowledge of their rights and the skills to challenge power. Where education is lacking, so too is the confidence to resist corrupt systems. People become observers rather than actors in shaping their nation’s future.

2. Employment

Without formal employment, people rely on informal or patronage-based systems. Jobs are secured not through merit, but through connections. This normalizes corrupt behavior as a means to survive.

The Afrobarometer Round 9 Survey (2022) reports a significant finding. More than 40% of Southern Africans believe that “who you know” is more important in securing a public job. This is more important than “what you know.” This belief doesn’t just show a reality—it reshapes it.

3. Justice

The justice system exists on paper, but access remains deeply unequal. For the poor, justice is often expensive, slow, or unsafe to pursue. When laws can’t protect, individuals choose systems that do—even if they are corrupt.

A Systemic Feedback Loop

Inequality and corruption are locked in a vicious cycle. Economic hardship drives people to tolerate corruption. That tolerance allows corruption to thrive. And corruption, in turn, deepens inequality by stripping resources, eroding trust, and dismantling public institutions.

To break the cycle, we must look beyond punishing individuals. We must redesign systems.

- Systems that make it easier to do right than to survive by doing wrong.

- Systems that restore faith in fairness, not only through legal frameworks, but by meeting real needs—jobs, education, dignity.

- Systems that allow communities to act not out of fear or silence, but with confidence and a collective voice.

Corruption wear the face of individual actors—but its roots grow in broken structures. And if we are to tackle it meaningfully, we must start by addressing the inequality that feeds it.

But here’s the catch: the moment of being caught is rare. Because corruption, by design, like any form of crime, often hides in plain sight. Crimes crafted by those deeply familiar with the framework are not meant to be discovered. In fact, evading detection becomes a twisted badge of intelligence. This is particularly true when their networks have neglected to recognize or reward that intelligence legitimately.

So we must ask ourselves: Are we content addressing corruption only when it’s exposed? Or do we have the courage to challenge the silent culture that allows it to thrive? That is Hendrik’s position.

Yet, a deeper question arises. Our society has reached this point because of a silent culture. This culture serves as a solution for society to avoid the pain of failure. What has caused us as societies, despite our distance from each other, to reach this same point?

It’s difficult to give precise percentages for corruption and economic crime incidents by continent as a percentage of the population. Data on specific incidences is often not publicly available or consistently collected across all countries and continents. Nevertheless, some generalizations can be made based on perception and reported levels of corruption, as well as known instances of economic crime:

Important Considerations:

Economic Development: In many cases, lower levels of economic development are correlated with higher levels of perceived corruption and economic crime

Data Collection: Gathering precise and comparable data across continents is challenging. The definitions and reporting approaches of corruption and economic crime vary.

Reporting Bias: Incidents are not reported accurately. This is common in countries with weak law enforcement. In such places, corruption is widespread, leading to under-reporting.

It is us. Just as Hendrik points out in his article, it is we who are faced with a choice. We choose to take the easier way out.

General Trends:

- Perceptions of Corruption: The Corruption Perceptions Index shows that many countries face different levels of corruption. Higher levels are seen in Africa, Asia, and South America. This is in contrast to countries in North America, Europe, and Oceania.

- Economic Crime: Economic crimes are reported globally. These include fraud, embezzlement, and money laundering. Their incidence is often higher in regions where legal enforcement is weaker. Corruption is more prevalent in these areas.

- Sub-Saharan Africa: The Organized Crime Index reports that corruption is a significant issue in many sub-Saharan African nations. This includes instances of tax evasion and smuggling. Some countries experience a higher prevalence of these issues than others.

- Asia: The Organized Crime Index suggests that Asian countries often face a mix of corruption. This corruption includes organized crime and money laundering. Such issues are prevalent, especially in countries with porous borders and less stringent regulations.

- South America: The Organized Crime Index notes that many South American countries experience high levels of corruption. This includes bribery, embezzlement, and money laundering. There are varying degrees of success in combating these crimes.

- Europe: Europe has a relatively low level of corruption compared to other continents. Yet, it is not immune to economic crime. Europe has a comparatively low level of corruption compared to other continents. Nonetheless, it is not immune to economic crime. Some regions, like Eastern Europe, have a higher prevalence of organized crime and money laundering.

- North America and Oceania: These regions generally have lower perceptions of corruption. They are considered to have more robust legal frameworks to handle economic crimes. They still face challenges.

Source: Google Search Labs / Generative AI

Understanding the roots of corruption requires more than just examining individual actions. It necessitates a deep dive into the systemic structures. Additionally, it requires an examination of the cultural norms that allow such behaviors. We will explore the various economic systems—free market, planned economy, social market economy, and tender-preneurship, within which these norms exist. This exploration uncovers how different frameworks either curb or cultivate corrupt practices. This analysis will shed light on the intricate relationship between economic models and the prevalence of corruption within communities.

Comparing Types of Economy

Here is a comprehensive contrast of five key economic models—Free Market, Planned Economy, Social Market Economy, Rentier Economy, and Tenderpreneurship—across multiple dimensions:

📊 Comprehensive Comparison Table

| Dimension | Free Market | Planned Economy | Social Market Economy | Rentier Economy | Tenderpreneurship |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic Control | Private individuals & firms | Central government | Private ownership + strong regulatory role by state | State or elite controls revenue from natural resources | Politically connected elites dominate access to contracts |

| Resource Allocation | Through supply & demand | Centrally planned | Market-driven but state ensures social equity | Revenue from rents (e.g. oil, minerals) rather than productivity | Allocated via state tenders, often bypassing market mechanisms |

| Employment Model | Market-driven; can lead to frictional & structural unemployment | Full employment via state assignment | Job creation is supported by state interventions & public-private cooperation | High public sector employment, private job creation is stunted | Jobs tied to government projects or tenders; high unemployment for outsiders |

| Innovation & Efficiency | High incentivized by competition | Low, limited incentives or flexibility | Balanced, supports innovation while mitigating inequality | Low incentive to innovate is weak due to reliance on natural rents | Low; focus is on securing contracts, not building scalable or productive ventures |

| Wealth Distribution | Can become highly unequal | More equal (artificially); often at the cost of efficiency | Moderately equal; supported by welfare, tax, education, and healthcare systems | Highly unequal; wealth concentrated in the ruling class or the state | Extremely unequal; wealth depends on political proximity rather than merit |

| Corruption Risk | Moderate; mostly via regulatory capture or monopolies | Low in theory; can be high in authoritarian regimes | Low transparency and the rule of law reduce corruption | High resource control often leads to elite capture and governance opacity | Very high; corruption is embedded in economic access and growth pathways |

| Governance Institutions | Independent but often influenced by private capital | State-controlled | A mix of independent institutions with strong state oversight | Weak accountability; institutions often serve elite interests | Compromised institutions; oversight often exists in form, not function |

| Public Services Delivery | Varies; often dependent on private sector capacity | State-driven; sometimes inefficient or poorly funded | Robust due to deliberate policy investment | Can be underdeveloped; focus is on rent collection, not citizen well-being | Services are politicized; tied to networks of patronage |

| Resilience to Shocks | Low to moderate; depends on diversification | Low, rigid, and slow to respond to economic change | High, the state can intervene to stabilize the economy | Low; highly vulnerable to commodity price swings | Low; the system is unstable and opportunistic |

| Examples / Analogues | USA, Singapore (hybrid), early UK capitalism | North Korea, former USSR, Maoist China | Germany, Sweden, France, South Korea (post-1990s) | Gulf States, Venezuela (oil era), Nigeria (some periods) | Zimbabwe (under Mugabe), parts of South Africa, Angola (in specific sectors) |

🧠 Key Insights

- Free Markets reward productivity and innovation, but can create deep inequalities and underemployment without state support systems.

- Planned Economies achieve equality and employment superficially, but often at the expense of freedom and economic dynamism.

- Social Market Economies offer the most balanced model, using state policies to make markets more inclusive, sustainable, and fair.

- Rentier Economies rely on natural resource rents. These rents can fund public goods. Yet, they often entrench elite dominance and discourage productive development.

- Tenderpreneurial Systems distort economic structures. They create access based on political ties rather than skill. This leads to fragility, inefficiency, and systemic corruption. Innovation and investment are not prioritized.

🔗 Likely Levels of Unemployment Across Different Economic Types?

Here is a breakdown of the likely levels of unemployment across the five major economic types. These are: Free Market, Planned Economy, Social Market Economy, Rentier Economy, and Tenderpreneurship. It also includes why unemployment tends to behave the way it does in each.

📊 Unemployment Patterns by Economic Type

| Economic System | Likely Unemployment Level | Key Characteristics & Causes |

|---|---|---|

| Free Market | 🔸 Moderate to High | Employment is based on supply and demand. Businesses hire based on profitability, not social need. During downturns, layoffs are swift. Structural and youth unemployment may be persistent. |

| Planned Economy | 🔹 Low (in theory) | Government assigns jobs to meet production quotas. Official unemployment is low, but underemployment and low productivity are common. The state often maintains artificial job security. |

| Social Market Economy | 🔸 Low to Moderate | The market drives job creation, but the state cushions shocks through public investment, social protection, and retraining. Unemployment is managed more strategically. |

| Rentier Economy | 🔸 High (especially youth) | Wealth from natural resources leads to a bloated public sector and neglect of productive sectors. Few private sector jobs. When rents decline, unemployment spikes dramatically. |

| Tenderpreneurship | 🔴 Very High & Unequal | Jobs are not created from productive growth but via elite networks and public tenders. Many skilled people stay unemployed while connected individuals cycle through contracts among themselves. |

🧠 Why These Patterns Matter

- In Free Markets, innovation and entrepreneurship may thrive—but only those with capital or skills benefit.

- Planned Economies prioritize full employment, but may create jobs that do not generate meaningful value.

- Social Market Economies manage the balance, cushioning the workforce while fostering economic growth.

- Rentier Economies offer short-term comfort but long-term fragility, especially for the unemployed majority without political or bureaucratic access.

- Tenderpreneurial Systems often produce elite employment bubbles, leaving youth and professionals sidelined from real economic participation.

🔗 Connected Insight: What Does Unemployment Have to Do with Corruption?

To fully understand the community’s silence around corruption, we must look at the deeper systems that shape people’s choices. A key one is unemployment.

In this companion post on unemployment in Botswana, I explore how widespread joblessness reduces citizens’ capacity to challenge corruption. When the formal economy excludes many, corrupt networks become the default path to income, security, and survival.

Lack of alternatives reinforces the silent societal order described in this article. Speaking out will mean losing access to the only channels available for basic needs, contracts, or employment. Silence, then, is not apathy—it is often a rational survival strategy.

To disrupt this cycle, we need more than anti-corruption frameworks. We need systems that offer people real choices through strong education pipelines, dignified employment, and regenerative industries. These are the focus of the unemployment study.

👉 Read the related piece: Case Study: National Unemployment in Botswana – Short Notes

Together, these two pieces reveal a key systems thinking truth:

We can’t fight corruption without transforming the systems that make people vulnerable to it.

Conclusion

Some societies lean toward planned economies for control and order. Others embrace free markets for innovation and wealth creation. Some balance both through social markets. Others slide into tender-preneurship when governance fails. These predispositions are not fate—but they are deeply influenced by history, institutions, culture, geography, and leadership.

Comparing Incidences of Corruption by types of economy

Here’s a comprehensive comparison of corruption tendencies across the five economic systems—Free Market, Planned Economy, Social Market Economy, Rentier Economy, and Tenderpreneurship—with insights into their structural vulnerabilities, types of corruption, and the systemic drivers behind them.

🧩 Corruption Across Economic Types

| Economic System | Corruption Incidence | Nature of Corruption | Systemic Drivers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Free Market | 🔸 Moderate | Regulatory capture, corporate lobbying, collusion in procurement, tax evasion | Weak regulation or over-liberalization, profit maximization over public good, insufficient enforcement |

| Planned Economy | 🔹 Low (visible), High (latent) | Nepotism, bribery for access to state-controlled goods/jobs, ghost workers | Centralized control, lack of transparency, and absence of market accountability |

| Social Market Economy | 🔸 Low to Moderate | Influence-peddling, elite lobbying, bureaucratic inertia | Balance between state and market creates room for negotiation and pressure from interest groups |

| Rentier Economy | 🔴 High | Elite capture of public resources, embezzlement, and patronage networks | Reliance on resource rents, weak diversification, poor institutional checks, and low citizen engagement |

| Tenderpreneurship | 🔴 Very High | Collusive tendering, kickbacks, inflated contracts, and political clientelism | Public procurement as a primary economic activity, blurred lines between business and state, lack of meritocracy |

📍Key Takeaways:

Free markets risk corruption when regulation is too lax or captured by vested interests.

Planned economies often conceal corruption under centralized systems; it festers within closed networks.

Social market economies mitigate corruption through accountability systems—yet they remain vulnerable to subtle forms of influence.

Rentier economies enable high-level, extractive corruption due to concentrated wealth and low institutional oversight.

Tenderpreneurial systems breed systemic corruption, making it a feature, not a bug, of economic activity—rewarding connections over competence.

Visual Summary (Incidence of Corruption)

| Market Type | Incidence of Corruption | Primary Source of Corruption |

|---|---|---|

| Free Market | Low to Moderate | Corporate regulatory evasion |

| Planned Economy | High | Bureaucratic exploitation |

| Social Market Economy | Low | Occasional public-private collusion |

| Rentier Economy | High | Elite capture of public resources |

| Tender-preneurship | Very High | Political patronage + state capture |

Why would one clamour for resources that one’s qualifications or merit will not command?

That question is relevant especially in systems where power, privilege, and opportunity are not always aligned with merit or qualification.

Here’s a breakdown of why someone clamours for resources beyond their qualifications:

🏆 1. Status Seeking in Unequal Societies

In many societies, resources = status.

- When educational pathways are perceived as slow, unfair, or inaccessible, people seek shortcuts to recognition and respect.

- Accumulating wealth or power—even without the “traditional” qualifications—becomes a way to claim legitimacy in society’s eyes.

“If society values what you have more than who you are, people will chase the symbol, not the substance.”

🛠 2. Broken Social Contracts

In places where education doesn’t reliably lead to opportunity, people stop believing in meritocracy.

- If graduates stay unemployed while politically connected individuals thrive, the perceived value of education diminishes.

- Clamouring for resources becomes a survival mechanism—not ambition, but adaptation.

“Why follow the rules when those who break them are rewarded?”

🧱 3. Historic Exclusion and Compensation

Some groups or individuals feel historically excluded from wealth or opportunity.

- The demand for resources reflects a wish to “catch up” or to reclaim dignity. This is especially true when others have inherited wealth or privilege without merit.

- This can fuel identity-based entitlement or resentment-driven accumulation.

“If I was shut out of the door for so long, I will now take everything behind it.”

🧑🤝🧑 4. Patronage Systems and Loyalty Economies

In environments where loyalty is valued over skill, people rise not by education but by allegiance.

- Resource access becomes a reward for loyalty to political or business elites.

- Those in these networks learn that “who you know” matters more than “what you know.”

“In patronage economies, qualifications are relationships—not degrees.”

🎭 5. Cultural Pressure to Execute

In hyper-materialist societies, external success is a survival language.

- People are often judged by what they own, not who they are.

- Without the qualifications to “deserve” resources, they overcompensate through material displays or aggressive acquisition.

“To be seen is to belong. And if qualifications don’t get me seen, I’ll find another way.”Why are some societies predisposed to certain economies?

Why are some societies predisposed to certain types of economies?

This question sits at the intersection of history, culture, geography, institutions, and power dynamics.

Here’s a breakdown of why some societies are predisposed to certain types of economies:

🧬 1. Historical Legacy

Societies often inherit the economic DNA of their past.

- Colonial economies were often extractive and centralized, laying the groundwork for planned economies or tenderpreneurial systems post-independence.

- Former capitalist colonies (e.g., Hong Kong, Singapore) often retained free-market or hybrid models with strong trade orientation.

- Post-revolutionary states (e.g., Cuba, USSR) leaned toward planned economies, shaped by ideology and anti-colonial sentiments.

“We organize economies not from scratch, but from memory.”

🏛 2. Institutional Strength and Design

The design of institutions—how they are structured, protected, and evolved—greatly determines economic direction.

- Strong, independent institutions (courts, press, legislature) support free or social market economies by enforcing accountability.

- Weak or politicized institutions often foster tender-preneurship and corruption, where power is centralized and contracts are politicized.

- State-centric political systems (like communist or authoritarian regimes) naturally lean toward planned economies.

“Institutions are the rails that guide the economic train. If they’re crooked, the train derails.”

🌍 3. Cultural and Social Norms

Some societies value collectivism, others individualism; some value tradition, others innovation.

- Societies that emphasize collective harmony prefer state-guided or social market models.

- Societies that prize entrepreneurial freedom and individual wealth gravitate toward free markets.

- In cultures where status and loyalty are prioritized over merit, tender-preneurship can emerge as a normalized practice.

Culture doesn’t decide the economy—but it shapes what is tolerated and rewarded.

🧭 4. Geographic and Resource Conditions

Natural resources, terrain, and location matter.

- Resource-rich countries often fall prey to the “resource curse,”—where wealth breeds elite capture and tenderpreneurial economies.

- Trade-focused island nations often adopt free or open-market economies out of necessity.

- Landlocked or remote states default to central planning for logistical and sovereignty reasons.

“Geography sets the table. Policy determines the meal.”

🧠 5. Leadership and Vision

The ideology of founding leaders and political elites profoundly shapes economic models.

- Visionary leaders like Lee Kuan Yew steered Singapore toward a hybrid, merit-based economy.

- Ideological leaders like Lenin or Mao instituted planned economies rooted in communist theory.

- Opportunistic leaders often embed tenderpreneurship, especially where checks are weak and political patronage thrives.

“Leadership chooses the rules. Society learns to play by them.”

Unmasking Corruption: A Systems Thinking Perspective

Understanding corruption as a systems challenge allows us to go beyond blaming individuals or pointing fingers at institutions. Systems thinking helps us explore why corruption persists, even in environments where anti-corruption policies and institutions exist. Two core tools help us here: feedback loops and mental models.

🌀 Feedback Loops: How Systems Sustain Corruption

Feedback loops explain how actions within a system either reinforce or balance change. In corrupt systems, reinforcing feedback loops (also known as “vicious cycles”) often overpower the balancing loops designed to promote accountability.

1. Reinforcing Loop: Power and Access Cycle

graph LR

A[Gain Power] --> B[Use Power to Access Resources]

B --> C[Strengthen Position]

C --> D[Build Patronage Networks]

D --> A

This loop explains how individuals or groups use power not just to serve, but to entrench themselves — reinforcing systems of privilege and corruption.

2. Reinforcing Loop: Fear and Silence Loop

graph LR

A[Someone speaks out] --> B[Faces Retaliation or Isolation]

B --> C[Community Becomes Afraid]

C --> D[Reduced Whistleblowing]

D --> A[Corruption Unchecked]

This loop illustrates why people stay silent even when they know something is wrong — the cost of speaking is too high.

3. Broken Balancing Loop: Weak Institutions

Balancing loops (e.g., laws, courts, audits) should curb abuse. But when institutions are underfunded, politicized, or lack autonomy, they fail to counteract reinforcing loops.

graph TD

A[Corrupt Action] --> B[Institutional Response]

B --> C[Sanction or Investigation]

C --> D[Deterrence]

D --> A

In many societies, this loop is broken between A and B — the system never gets to deterrence because there’s no credible investigation or sanction.

🧬 Mental Models: The Hidden Operating System

Mental models are the deeply held beliefs, values, and assumptions that govern behavior. These are often unspoken, yet they shape how entire societies respond to corruption.

| Prevailing Mental Model | Impact on Corruption | Shift Needed |

|---|---|---|

| “Everyone does it.” | Normalizes misconduct | Showcase role models who resisted corruption |

| “Connections matter more than competence.” | Erodes meritocracy | Promote transparency in hiring and procurement |

| “Speaking out is dangerous.” | Protects abusers | Strengthen whistleblowers protections |

| “The law only applies to the poo.r” | Fuels cynicism and resignation | Guarantee equal justice regardless of status |

When these mental models go unchallenged, they create an invisible wall that keeps society from changing.

🌐 Regional Case Studies: Southern Africa in Focus

Botswana: Institutional Strength Amidst Emerging Risks

Botswana has long been recognized for its relatively low levels of corruption. This is in comparison to regional peers. The low levels are attributed to strong legal frameworks and a tradition of bureaucratic meritocracy. Yet, recent concerns have emerged about procurement-related corruption, particularly under emergency powers during COVID-19. This highlights the breakdown of the balancing loop when oversight mechanisms are bypassed.

South Africa: The Zondo Commission and the Cost of Silence

The Zondo Commission’s findings on state capture revealed the impact of reinforcing feedback loops. These loops, built through networks of patronage and fear, corroded South African public institutions. Despite the existence of laws and enforcement bodies, internal collusion neutralized the balancing loop. A mental model also discouraged whistleblowing. Testimonies from public servants who spoke up underscored the personal costs of breaking the silence.

Zimbabwe: Parallel Structures and Patronage Economies

In Zimbabwe, corruption has become deeply entrenched. This occurs in the form of tenderpreneurship. State contracts are distributed through political loyalty. Feedback loops here include cycles of political protection, economic dependency, and public disillusionment. These loops are further sustained by a mental model that perceives political affiliation as a prerequisite for economic survival.

🚀 Transforming Systems Through Awareness and Design

To dismantle entrenched corruption, we must as Hendrik points out in his article, pay attention to the following:

Make loops visible. Use storytelling, data, and visuals to reveal how patterns of power and silence operate.

Weaken negative reinforcing loops. Create social consequences for unethical behavior and protect those who stand up.

Strengthen balancing loops. Invest in robust, independent institutions that act quickly and fairly.

Challenge mental models. Engage communities in dialogue, education, and re-framing of what leadership and justice look like.

As Peter Senge writes in The Fifth Discipline, “The structures of which we are unaware hold us prisoner.”

The more we surface these structures — loops and beliefs — the freer we become. We gain the freedom to design a just and transparent system.

Conclusion

The economy commands more attention from its external market. This happens when it participates freely within a good strategic plan for itself. It also involves its regional partners. As it depends less on patronage systems or loyalty economies, its people are less predisposed to corruption. They pay less attention to using corrupt means to acquire wealth. Society’s focus on corrupt ways to acquire wealth has spiraled out of control long before we see cases of corruption. This focus on corrupt ways to acquire wealth has become unmanageable.

When systems don’t reward competence, people seek power through other means. The problem is not always with the individual. The issue often lies in the values of the system. It is also found in the structure of opportunity and the broken trust between merit and mobility.

You must be logged in to post a comment.