This is the first study of its kind in the field of Learning Organisation. It is also the first application of The Fifth Discipline on a national scale. It is a significant achievement not just for me but for the global community of practitioners at large.

We would be delighted to share insights into Systems Thinking as a research methodology. I am pioneering this approach for global application. My work focuses on developing structured frameworks for large-scale interventions. This aligns with Peter Senge’s advocacy for integrating Systems Thinking with robust data and research. This approach has gained recognition within the global SoL community. It highlights the need for more researchers. This need exists alongside government, business, and community leadership practitioners.

SUPPORTING LINKS:

Core link – Unemployment Study

Part 1 – Current Situation: https://sheilasingapore.blog/addressing-persistent-unemployment-in-botswana-a-systems-thinking-approach-part-1/

Part 2 – Areas of Leverage Interventions: https://sheilasingapore.blog/addressing-persistent-unemployment-in-botswana-a-systems-thinking-approach-part-2/

Supporting links – Governance and Value-Chain Structures:

Cross-Sectoral Growth Planning and Governance Structure: https://sheilasingapore.blog/2025/06/26/when-the-world-speaks-governance-bw/

What the Public Sector Can Do To Get Ready to Let the Private Sector Lead: https://sheilasingapore.blog/2025/06/04/when-the-world-speaks-national-development/

KEY DEPARTURE POINTS BETWEEN OUR UNEMPLOYMENT STUDY AND THE BETP DIAGNOSTIC FACT PACK

As of 31 July 2025

🎙️ KEY TALKING POINTS FOR PRESENTATION, INTERVIEWS OR PANEL DISCUSSIONS

🧭 1. Framing the Unemployment Crisis as a Systemic Design Problem

- Botswana’s high unemployment is not just an economic outcome—it’s a symptom of deeper systemic misalignment.

- The current system does not connect education, economic participation, and enterprise development effectively.

- We must change our focus. Instead of asking how to get people into jobs, we should ask how to build systems that produce jobs naturally. Instead of asking how to get people into jobs, we should ask how to build systems that produce jobs naturally.

⚖️ 2. Mismatch Between Economic Sectors and the Labor Market

- Too much focus on resource extraction (especially mining) with little trickle-down employment.

- Agriculture and manufacturing—sectors with job creation potential—are underdeveloped.

- A systems approach would focus on rebalancing these sectors to absorb both skilled and unskilled labor.

📚 3. The Education and Skills Pipeline is Disconnected

- There is a lack of alignment between the education system and real-world job demands.

- Few graduates emerge with the technical, entrepreneurial, or STEM-related skills needed to compete globally or innovate locally.

- Reform is needed to transform schools and tertiary institutions into centers of productivity and innovation.

🧑🏽🤝🧑🏾4. The Role of Family Structure in STEM Capacity

- Restoring balance within households—especially through gender-balanced parenting—is critical to developing Botswana’s national capacity in STEM.

- The study finds that without strong foundational support at home, particularly for cognitive development in the hard sciences, broader reforms in education, employment, or economic policy are unlikely to achieve lasting success.

🧑🏽🤝🧑🏾 5. The Entrepreneurial Narrative is Overstretched

- While entrepreneurship is important, pushing everyone toward it often ignores structural barriers like:

- Lack of startup capital

- Weak value chains

- Low local demand

- We need to rebuild labor markets and firm ecosystems before individual entrepreneurship can thrive equitably.

🧠 6. Mindsets, when adopted, Better Foster the New Economic System

- Society often sees employment as a government responsibility or a solo effort.

- Instead, build the tools that provide the capacity to interrupt automatic patterns in thinking and action, allowing for the shift of or growth of needed mindsets: citizens as productive co-creators of jobs for the unemployed, not just job seekers.

- This requires building family systems, business culture, and policy environments that reinforce productivity, collaboration, and dignity.

🌍 Calls to Action for Policymakers, Educators & Investors

- Foster ecosystems that connect STEM education, vocational training, and real sector development.

- Build regional food and manufacturing value chains that absorb labor and build export competitiveness.

- Create incentives for firms to hire, train, and keep local talent, not just automate or outsource.

WHAT ECONOMIC MODEL SUITS A SMALL NATION ASPIRING TO ACCELERATE ITS ECONOMIC AND POPULATION GROWTH?

For a country with a stable but stagnant population (~2 million for 20 years), it plans to accelerate economic growth. It also aims to boost population growth to align with global ambitions. The best economic model is a Social Market Economy with Strategic Industrial Planning. This would be supported by systems thinking principles.

Here’s why:

🌍 Recommended Model: Social Market Economy (SME) + Strategic Industrial Development

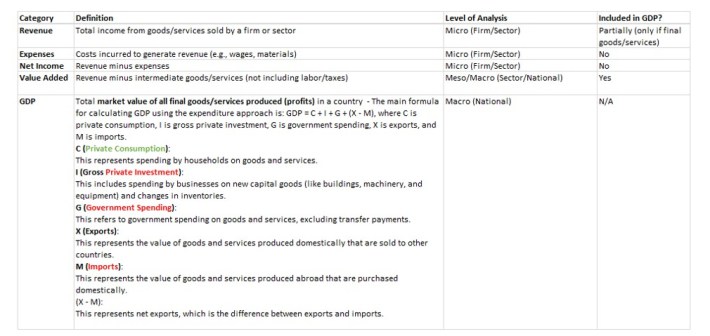

| Aspect | Reasoning |

|---|---|

| Human-Centered Growth | SME balances free enterprise with social policies. It ensures that while markets are active, equity, health, education, and dignified work are not compromised. This matters for a small country aiming to scale responsibly. |

| Population Incentives | A socially inclusive economy can create trust in institutions, making it more likely that citizens will stay, return from diaspora, or start families. It can also attract ethical migration. |

| Industrial Strategy | Pair SME with selective planning in agriculture, manufacturing, and digital sectors. Invest in value chains that export, reduce imports, and generate jobs. Focus on STEM-based education. |

| Avoids Rent-Seeking Traps | SME limits the risks of corruption and elite capture. This is often seen in tenderpreneurship or rentier economies. In these economies, resource control is concentrated, and unemployment remains high. |

| Builds Resilience | Allows private investment and innovation while protecting against shocks—be they economic, environmental, or demographic. Resilience is key when transitioning from a small base to international relevance. |

✨ Case Comparisons:

- Botswana is an example where initial growth under a hybrid model worked, but growth has since stagnated. Moving toward a social market economy could rejuvenate momentum to avert abject poverty, but not sustain economic growth in the long term.

- Singapore (with a smaller population) succeeded through state-led industrial planning within a competitive market, emphasizing education, housing, and ethics.

🔧 KEY POLICY LEVERS TO ACTIVATE

- Reform education toward STEM, science application, innovation and technical skills, and entrepreneurship.

- Strategically invest in regenerative agriculture, green manufacturing, and clean energy.

- Support family systems and community care models to facilitate population growth.

- Strengthen public trust and reduce corruption by creating transparent institutions.

- Attract ethical investors and diaspora professionals who can contribute to nation-building.

WHAT IS A PERSISTENT NATIONAL ISSUE?

A persistent issue like unemployment is not just a series of isolated causes and effects—it is a carefully structured trap. That is why such problems endure, whether we acknowledge them or not. Like all traps, they stay concealed. Think of how a mousetrap is set up—effective only when unnoticed.

Uncovering these traps is the core goal of these studies. These traps come in the form of mental models, ingrained mindsets, or broader systemic forces.

WHY WE SHARE THESE CASE STUDIES: FROM INSIGHT TO ACTION

These presentations are best absorbed without haste. An untrained mind instinctively resists unfamiliar insights. This resistance reinforces the very traps we seek to escape.

Persistent issues such as unemployment are rarely the result of isolated causes. They are the product of carefully structured systems—traps that endure not because we ignore them, but because they are often invisible. Like a well-set mousetrap, they remain effective precisely because they go unnoticed.

Each case study invites us to slow down and look again. These traps often take the form of outdated mental models, entrenched mindsets, or broader systemic forces. Our goal is to make the invisible visible—so that lasting change becomes possible.

So before you move on, we invite you to sit down with a cuppa. Give yourself the space to reflect, to ask the harder questions, and to see the system beneath the symptoms. Because the next person who makes a difference might just be you. This reminds us that deep systems insight requires presence, reflection, and a slowing down—not just intellectual agreement.

If this study sparked something in you—an insight, a question, or a next step—don’t leave it there. Share it, discuss it, or reach out to us at STRLDi. We’re always looking for fellow system-shapers to walk this path together.

Brief: Urgent Need for Employment-Centered Economic Design

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: UNLOCKING BOTSWANA’S EMPLOYMENT POTENTIAL

Botswana’s persistent unemployment challenge, despite decades of policy interventions, highlights the need for a fundamental shift in economic strategy. Economists, government policymakers, and business planners need a systemic approach. This approach should address structural causes rather than short-term fixes.

A balanced emphasis on agricultural and industrial development can create diverse employment opportunities, reducing dependency on a single sector.

Strengthening STEM education is also crucial in equipping the workforce with skills relevant to the modern economy. Government policies should support innovation, entrepreneurship, and infrastructure that enable job creation. Businesses must invest in skill development and sustainable industrial growth to align with these efforts.

A coordinated, long-term strategy integrating these elements will be essential in transforming Botswana’s labor market and ensuring inclusive economic resilience.

TODAY’S SITUATION

Investments to-date (1960s–Present)

Since Independence, Botswana has received an estimated USD 1.2 trillion (≈ P16 trillion) in investments, government spending, and aid. Over the same period, our population has grown from approximately 580,000 in 1966 to around 2.7 million today. This translates to roughly USD 600,000 (≈ P8 million) invested per person over five decades—excluding inflation adjustments (sources: The Guardian, Reuters, Wikipedia).

As of Q1 2024, approximately 504,738 individuals are formally employed in Botswana—defined as those holding wage or salary jobs in the formal sector (VCDA.afdb.org, Trading Economics, Botswana LMO).

To put this in context:

- The average monthly wage in the formal sector is P7,149 (~USD 500) (Stats Botswana Q1 2024, ILO, Botswana LMO).

- Botswana’s total labor force is estimated at 1,173,186 individuals.

- Therefore, only 43% of the labor force holds formal employment.

This is clear evidence that decades of investment have not translated into shared prosperity.

Despite numerous policy interventions, unemployment in Botswana has remained persistently high. With just 43% formally employed, and an estimated 1.5 million working-age individuals, this leaves 57%—nearly 6 in 10 employable people—without access to sustainable income.

Long-Term Productivity Insights (1970–Present)

1. Botswana’s Labour Productivity Trends

According to the International Labour Organization (ILO) and World Bank data:

- Labour productivity (GDP per employed person) in Botswana has grown steadily since the 1980s, largely driven by mining revenues.

- However, the growth curve has flattened in the past two decades, with only marginal gains in real output per worker, indicating that productivity improvements have not kept pace with capital investments.

- As of the latest data (2022–2023), Botswana’s labour productivity is below the average of high-income countries, and lags behind some peers in Asia (e.g., Vietnam and Malaysia).

2. Regional Comparisons

- South Africa: Although facing labour rigidity, its productivity per employed person is higher due to more advanced industrialization and stronger technical institutions.

- Vietnam: In the 1980s, it was behind Botswana in GDP per capita and productivity but has surpassed Botswana in both output and export-led productivity gains, especially in manufacturing and agriculture.

- Rwanda and Ghana: Their labour productivity is still catching up, but they show stronger multi-sectoral investment coordination, particularly post-2015.

3. Data Limitations

While there is consistent GDP per worker data, there is less detailed behavioural data on work culture, institutional effectiveness, and contribution of informal sectors, which are critical in understanding “why” productivity diverges despite investments.

Labour Productivity Ranking By Countries

Here’s the consolidated productivity table, alongside Botswana, Luxembourg, and global leaders:

| Country / Region | Productivity (USD/hr, PPP) | Productivity (USD/worker, PPP) | Global Rank (hour-worked) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ireland | ~162.5 | ~188,876 | 1 (World Population Review, Wikipedia) |

| Norway | ~161.8 | ~183,652 | 2 (World Population Review, Wikipedia) |

| Luxembourg | ~130.7 | ~155,000 | 3 (World Population Review, Wikipedia) |

| United States | ~71.9 | ~129,000 | ~30 (Wikipedia, World Population Review) |

| Canada | ~70.9 | ~123,000 | ~31 (Wikipedia, World Population Review) |

| Israel | ~58.5 | ~107,000 | ~40 (Wikipedia, World Population Review) |

| Japan | ~53.4 | ~97,100 | ~43 (Wikipedia, World Population Review) |

| South Korea | ~50.1 | ~88,000 | ~46 (Wikipedia, World Population Review) |

| Singapore | — (not published) | ~140,280 – 147,118 | not ranked (hour) (Wikipedia, Brilliant Maps) |

| Malaysia | — (not published) | ~35,300 – 39,300 | not ranked (hour) (Wikipedia) |

| Chile | ~35.5 | ~67,500 | ~60 (Wikipedia, World Population Review) |

| Mexico | ~24.0 | ~41,200 | ~65 (Wikipedia, World Population Review) |

| Botswana | — (not published) | ~23,338 | ~61 (GDP per worker) (mydatajungle.com) |

Notes & Context

- For Singapore and Malaysia, reliable data on GDP per hour worked aren’t consistently published by OECD or ILO; hence “—” appears in that column. However, GDP per worker (output per employed person) is available:

- Singapore’s GDP per worker is estimated at approximately $140,300 – $147,100 (constant 2021 PPP USD), per Conference Board total economy database statistics (Brilliant Maps, The Conference Board).

- Malaysia’s GDP per person employed is estimated at $35,300 – $39,300 (constant PPP USD), ranking it around 62nd globally, ahead of China, Indonesia, Vietnam, etc. (Wikipedia).

- Botswana’s GDP per worker stands at roughly $23,338, placing it at about 61st globally (mydatajungle.com).

- Rankings by hour worked are based on OECD data for 2022; some countries like Malaysia and Singapore are unranked in that metric due to data gaps.

Interpretation

- Luxembourg, Ireland, and Norway dominate in productivity per hour, showing nearly double or more output than high‑income countries in the Americas and Asia.

- In per-worker terms, Singapore outperforms many high-income economies despite missing per-hour data.

- Botswana, while lower in output per worker than Asian or Western peers, is close to the middle tier globally.

- Malaysia’s per-worker output is modest and significantly below OECD high-income benchmarks.

- Countries like Chile and Mexico perform lower both per hour and per worker, reflecting broader regional productivity gaps.

Labour growth centred in non-revenue generation markets

Botswana’s economy is built primarily around the public sector, beside the mining sector, with participation from private investors and state-owned enterprises. Yet it continues to lag behind population growth. Despite a 16–20-year lead time before individuals enter the labor force, there is no mechanism in place to ensure sufficient job creation in the broader bases of the economy, such as agriculture and manufacturing sectors. As a result, about 1 million people remain outside the formal economy, with no structured pathway to enter it.

To reverse this trajectory, Botswana must shift from passive job absorption to deliberate labor market design. This means:

- Prioritizing labor-intensive, high-growth sectors like manufacturing and agriculture.

- Making an aggressive push for STEM skill development.

- Ensuring educators with globally benchmarked expertise lead the transformation—so that the workforce becomes not just employable, but globally competitive.

Our unemployment study—rooted in over 20 years of data—reveals the core problem: only ~10% of graduates specialize in STEM or technical fields, leading to a severe skills mismatch. This prevents growth in agriculture and manufacturing. Meanwhile, instability at the household level, particularly the declining presence of male figures, erodes early exposure to STEM learning and limits technical capacity development.

An ill-equipped labor force stays trapped in low-productivity, low-wage sectors, unable to power enterprise growth or raise national incomes. Businesses, in turn, cannot scale or offer better pay. Unless job creation is built into the structure of economic expansion, the workforce will continue to outpace available opportunities, deepening economic stagnation.

Certainly. Here is the content structured into a three-paragraph write-up with a suitable sub-paragraph title:

When Earning Isn’t Enough: The Circulation Crisis

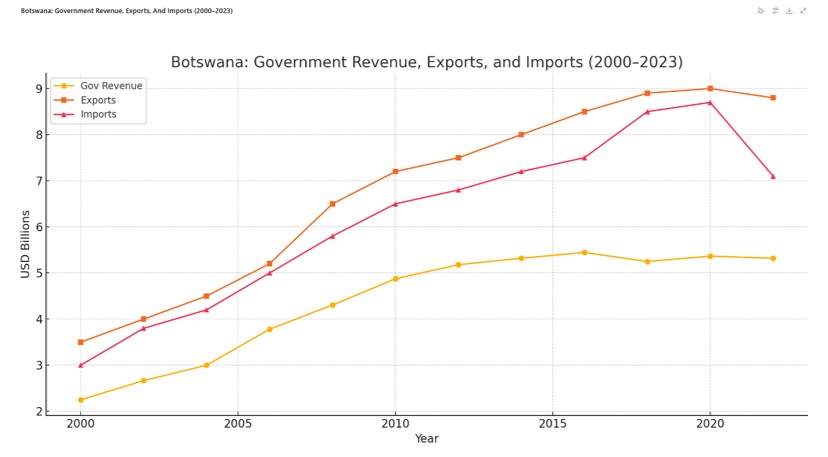

Botswana has built an impressive track record of export-led earnings and prudent fiscal management, but a deeper issue persists beneath the surface: the money we earn does not stay in the economy long enough to generate sustained impact. Instead, it exits almost as quickly as it enters—through imports, repatriated profits, external contracts, and other financial leakages. This pattern undermines the very purpose of economic growth. It’s not that Botswana doesn’t earn—it does. The problem is that those earnings don’t multiply within the local economy, depriving it of the fuel needed to create jobs, deepen industries, or uplift communities. This paper unpacks the scale of that leakage, where it goes, what remains, and what must be done to reverse it.

Exporting Wealth, Importing Dependency

It is a fair and data-backed observation that a substantial share of the income Botswana earns—whether through exports, government revenue, or trade—does not stay within the economy but instead exits rapidly. This dynamic is particularly evident in years like 2022, when Botswana exported approximately USD 8.9 billion worth of goods, yet spent about USD 8.7 billion on imports. That means nearly every pula earned through international trade was matched by a pula spent abroad. The result is a system where revenues generated through diamonds and other exports flow out just as quickly via imported fuel, machinery, vehicles, food, and services, with little absorption into domestic value chains. Without robust processing, manufacturing, or reinvestment capacity, the economy behaves like a conduit rather than a container—passing wealth through without compounding its benefits locally.

How Much Leaves, How Little Stays

In estimating the leakage, if we treat total exports (≈ USD 8.9 billion) as a proxy for total revenue, and combine import spending with factors like profit repatriation, external contract payments, and debt service, a conservative estimate suggests that at least 60–80% of this national income leaves the country. That means only 20–40% of what Botswana earns circulates internally—supporting government wages, local consumption, and limited domestic procurement. In 2022, for example, government revenue stood around USD 5.5 billion, while import bills were higher still at USD 8.7 billion—making imports roughly 158% of revenue. This points to a structural imbalance where even sovereign income is insufficient to retain wealth domestically.

The Need to Build Domestic Multipliers

What little money remains is spent primarily on public salaries, social services, and recurring operational costs, which in turn often rely on imported inputs—thereby creating additional layers of leakage. Without strengthening Botswana’s domestic production capacity—especially in manufacturing, agriculture processing, and infrastructure development—these funds will continue to create jobs and incomes elsewhere, not at home. The weak local value chain not only limits domestic job creation but also increases vulnerability to external price shocks and supply disruptions. Unless this economic architecture is reshaped to prioritize internal circulation and value capture, Botswana may continue to earn big but circulate little—leaving a growing population without the employment or enterprise opportunities it deserves.

High Dependency Ratio

The consequences are staggering:

Each formally employed person today supports an average of 5.4 dependents—nearly 10 times the dependency ratio of Germany (0.6). This cripples economic mobility and reinforces the cycle of joblessness.

This is not a failure of effort—it is a systems failure.

Traditional interventions have targeted symptoms, not the underlying structures that entrench unemployment.

This report uses The Fifth Discipline and Systems Thinking to uncover the hidden dynamics sustaining this crisis. It identifies feedback loops, systemic traps, and leverage points that offer a path forward.

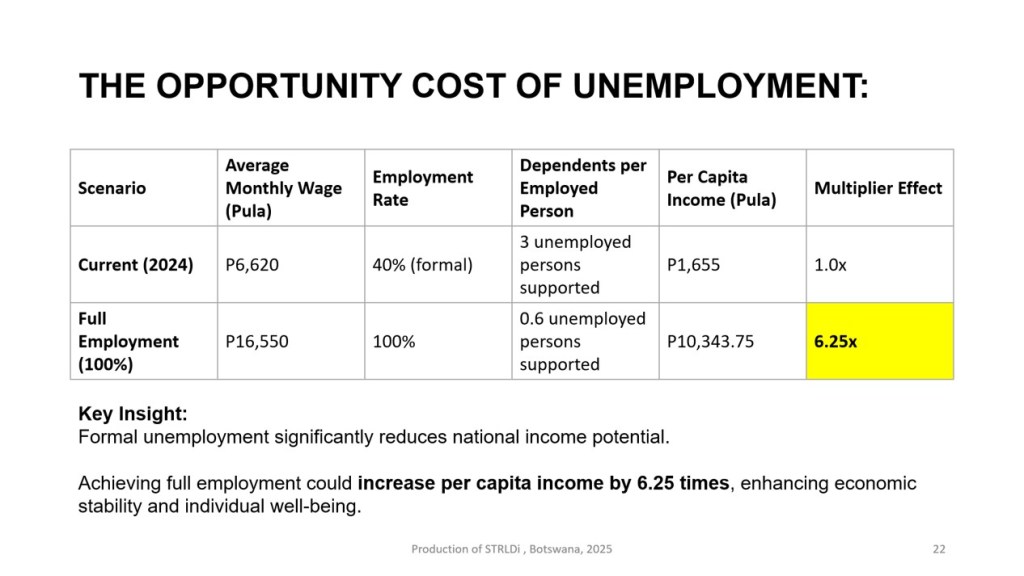

The shift from piecemeal fixes to structural transformation can unlock massive gains: per capita income could rise from P1,655 to P10,344.

Real economic transformation doesn’t come from picking low-hanging fruit. It comes from cultivating an ecosystem where prosperity can take root—and flourish.

WHAT TO EXPECT WHEN USING SYSTEMS THINKING

Systems thinking provides economists with a powerful framework to tackle complex economic challenges. It shifts from reductionist analysis to a holistic understanding of interdependencies. Unlike traditional linear models, it emphasizes feedback loops, long-term effects, and cross-sectoral dynamics, revealing leverage points for policy intervention. By focusing on relationships instead of isolated factors, systems thinking enables more adaptive and resilient economic strategies. It fosters sustainable growth, industrial development, and labor market efficiency. This approach is particularly crucial for economies like Botswana’s. In these economies, sectoral integration and structural transformation are key to reducing unemployment. They also enhance productivity.

For economists, systems thinking is counterintuitive. It highlights the complexity of economic interventions. Well-intended policies can lead to unintended consequences. Traditional economic models often assume linear relationships, but real-world economies function as dynamic systems with feedback loops, delays, and interdependencies. Quick fixes, like subsidies, price controls, or labor regulations, offer short-term relief. Yet, they can distort market signals. These distortions create inefficiencies or exacerbate underlying problems. Systems thinking encourages policymakers to find leverage points that drive sustainable economic growth. It emphasizes long-term strategies over reactive measures. This approach helps build resilient and adaptive economies.

A nation’s economy reveals intricate mechanisms. Systems thinking—seeing the forest for the trees—helps us understand what drives growth, employment, and sustainability. This approach aims to identify the key factors shaping economic performance. It assesses whether the system is effectively structured to absorb its working-age population. When an economy fails to provide sufficient opportunities, the consequences manifest as persistent or acute unemployment. This limits both individual prosperity and national development. This study begins by examining these dynamics. It explores how structural adjustments, sectoral linkages, and policy interventions can enhance economic resilience. These strategies also promote inclusive growth.

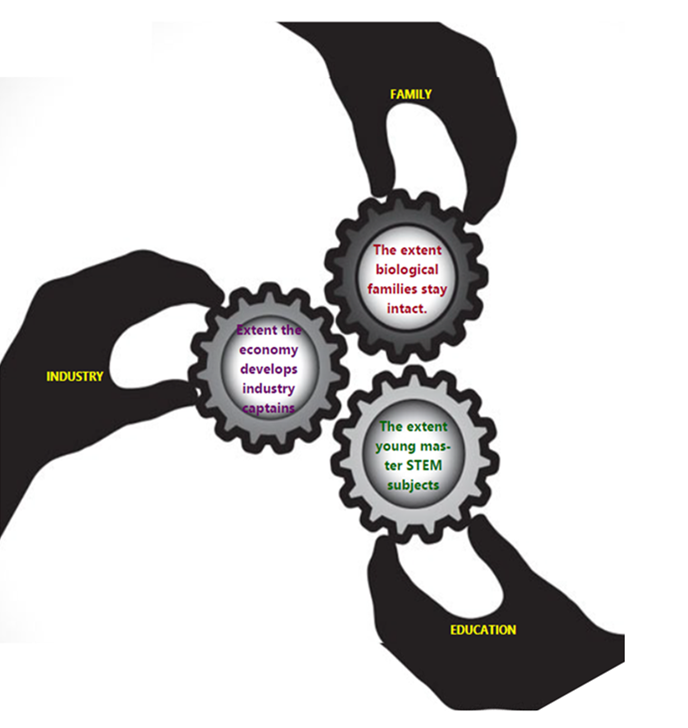

It describes three key interrelated components of a nation. When these components work together, they guarantee that as the population grows, the economy also expands. This creates a robust, well-functioning system that becomes broad-based, well-oiled, and resilient for the long term.

HOW TO USE THE RESULTS OF THE STUDY

The study presents thinking on several fronts:

#1: Communities and families need to nurture strong core family relationships. These relationships contribute to a child’s holistic understanding of both hard and soft sciences equally.

#2: Focusing on vital economic sectors will generate employment opportunities. This ensures the inclusion of 70% of the working-age population currently not engaged in formal employment.

Emphasizing education and professional development in STEM subjects from primary school levels is crucial. Long-term personnel employment in agricultural and manufacturing sector development is essential. This strategy is pivotal for fostering leadership in economic sectors. It substantially boosts overall employment growth.. This approach fosters leadership in economic sectors. It substantially boosts overall employment growth. It’s essential to note that for each person not formally employed, the country loses P6,000 per person monthly. This is a key factor in addressing economic challenges.

#4: The government acknowledges its limitations. It emphasizes the pivotal role of industry captains in the private sector. The private sector, community, and family development structures also play crucial roles in effective management and governance.

WHAT IF BOTSWANA CREATES 6 MILLION JOBS?

We have depended on short-term solutions for too long. We pursued the easiest paths, including vocational training programs, foreign investment incentives, and youth empowerment schemes. These traditional interventions have been well-intentioned. However, they have largely failed to break the cycle of persistent unemployment. This issue is prevalent not just in Botswana but across the continent.

But what if we dared to think bigger? What if Botswana creates 6 million jobs? This would be enough for full employment for every Motswana. It would also create millions more opportunities for future generations. This is not an unattainable dream. It is a challenge that requires fundamental shifts in thinking and a bold departure from conventional approaches. We can no longer afford to delay. Haven’t we postponed this long enough?

To truly transform our employment landscape, we must first recognize the counterintuitive nature of the solution. The study challenges us to look beyond the obvious. It encourages us to explore factors deeply embedded in the framework. These factors are not directly within the control of policymakers.

Secondly, we must actively involve those who have been left on the margins of the economy. These are the very people who have the most to gain from meaningful change. The growing economic divide can no longer be ignored. Without their engagement and understanding of this approach, Botswana can’t reverse the persistent cycle of national unemployment.

The question is not whether we can achieve this. The question is whether we are ready to embrace the shifts needed to make it happen.

PREAMBLE

Unemployment is not just a statistic—it is a growing challenge that affects families, communities, and the entire nation. The number of people entering the workforce increases due to births. As a result, job creation struggles to keep up. Businesses can only hire when they are profitable. This imbalance leads to a reinforcing cycle where unemployment continues to rise exponentially. Breaking this cycle requires action—investing in skills, entrepreneurship, and policies that support business growth. When businesses thrive, they create more jobs, reducing unemployment and improving the well-being of everyone.

Why has unemployment remained resistant to our efforts aimed at reversing it?

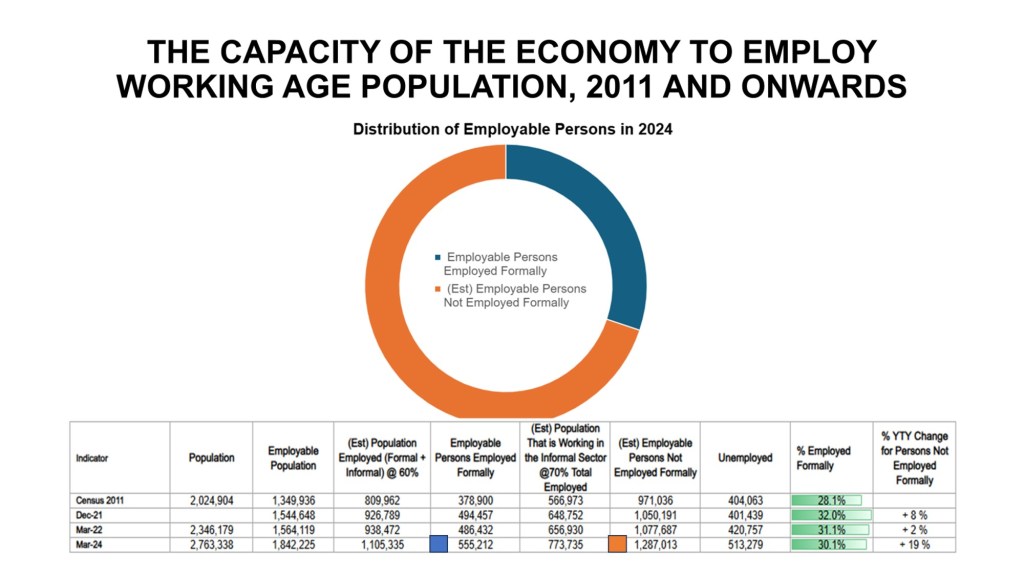

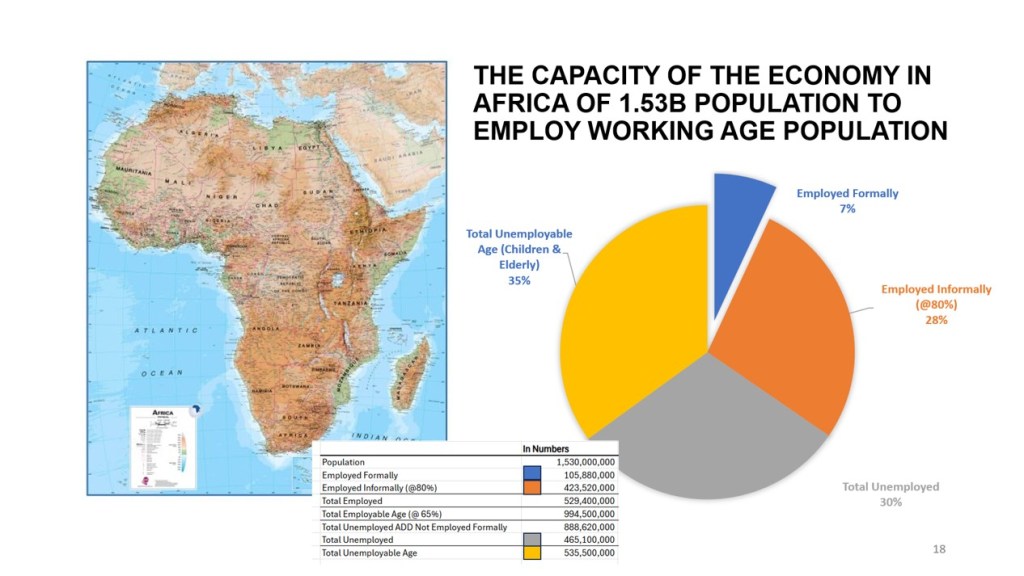

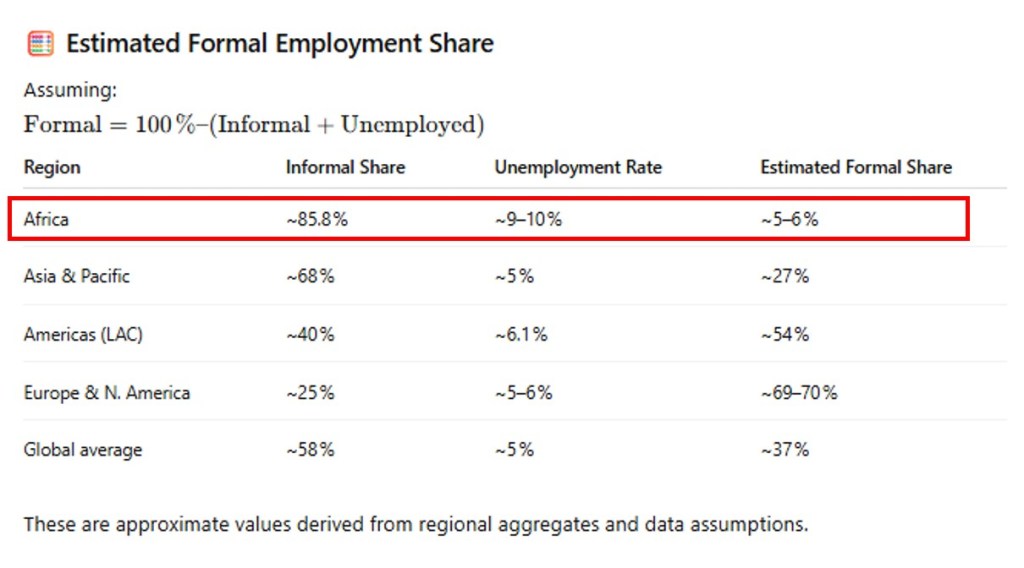

CAPACITY OF THE ECONOMY TO ABSORB WORKING-AGE POPULATION TODAY

The data highlights a critical challenge for economists, government policymakers, and business planners. The economy has a limited capacity to absorb the growing employable population into formal employment. The total employable population has increased significantly. Yet, the proportion employed formally has remained stagnant or declined slightly. This indicates structural constraints in labor market absorption. The number of individuals working in the informal sector is rising. Many stay unemployed. This situation highlights the need for policies that foster job creation. These policies should also improve labor market efficiency. Additionally, they should encourage formal sector expansion. Governments must emphasize skills development. They must invest in infrastructure and implement business-friendly regulations to stimulate formal employment. Meanwhile, businesses should explore scalable models. These models should integrate informal workers into more structured, productive roles. Economic planners should consider long-term strategies. They need to balance labor supply and demand. This will ensure sustainable economic growth and social stability.

The employment challenge illustrated at the national level is no different for the continent of Africa. Only 7% of the employable population is formally employed. Meanwhile, 80% of those working are engaged in informal jobs, leaving nearly 30% unemployed. This structural imbalance highlights critical gaps in economic planning, labor market policies, and industrial development strategies. For economists, government policymakers, and business planners, these figures emphasize an urgent need. Large-scale investments in formal job creation are necessary. Investments in skills training and infrastructure can also help achieve sustainable employment. Governments must implement policies that support small and medium enterprises (SMEs). They must enhance labor regulations to transition informal workers into the formal sector. Furthermore, they should create an enabling environment for industries that generate stable employment. Business leaders should explore inclusive growth models. These models should integrate informal workers into more structured, productive roles. Economic planners need to drive long-term strategies. These strategies should align education, workforce development, and industrialization efforts to accommodate Africa’s rapidly growing population.

THE OPPORTUNITY COST OF PERSISTENT UNEMPLOYMENT

Unemployment affects everyone, not just those without jobs. When many people are unemployed, families struggle, businesses lose customers, and the entire economy slows down. Right now, each employed person is supporting multiple dependents, making it harder for families to thrive. If Botswana reaches full employment, average wages rise significantly. Per capita income increased by more than six times. This would lead to a better quality of life for all. More jobs mean less financial stress, stronger communities, and a brighter future for the next generation. Investing in skills, education, and job creation is the key to making this a reality.

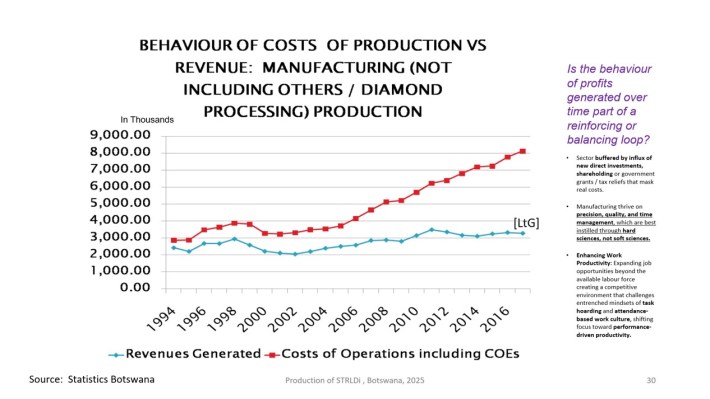

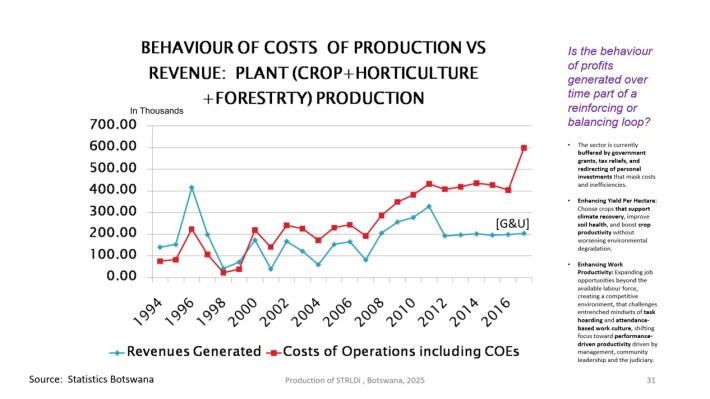

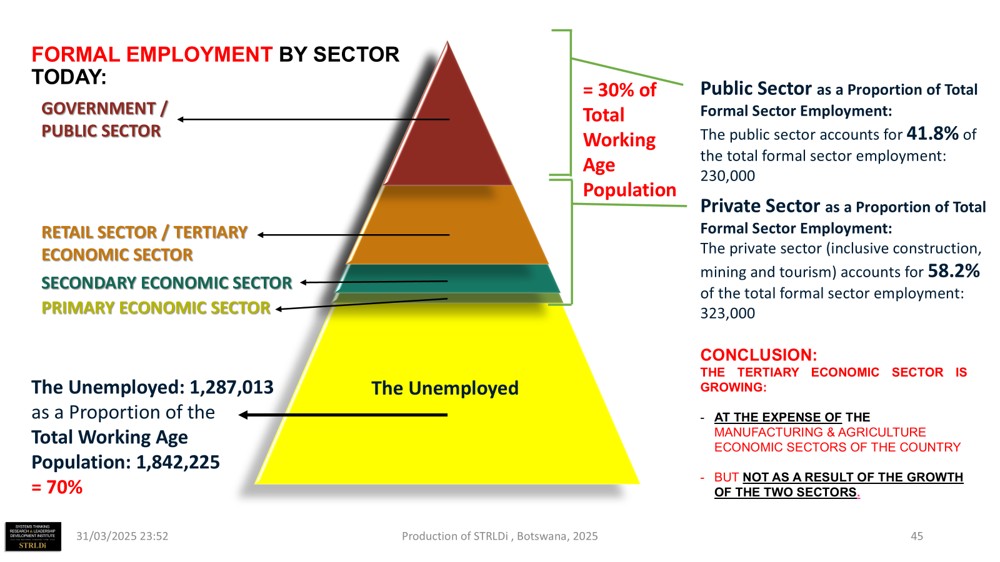

THE CAPACITY OF ECONOMIC SECTORS TO CREATE EMPLOYMENT

The retail sector has emerged as the driving force of the economy. It surpassed the mining sector in 2008. It has been continuing to grow. This shift highlights the increasing role of commerce, services, and consumer demand in shaping economic progress. Unlike mining, which relies on finite resources, the retail sector thrives on innovation and entrepreneurship. It also thrives on the ability to meet people’s evolving needs. With rising revenues outpacing costs, this sector presents opportunities for job creation, business expansion, and economic resilience. Investing in skills, digital transformation, and local enterprises can further strengthen this vital part of the economy.

Once the backbone of the national economy, the mining sector has faced increasing volatility since the 2008 global financial crisis. The sector struggles now with fluctuating revenues. It also faces rising competition from lab-grown diamonds. These diamonds attract global consumers with lower prices. Although there is potential for recovery as global economies strengthen, the path to resurgence remains uncertain. There have been no clear signs of sustained growth over the past two decades. This uncertainty calls for economic diversification and investment in industries that offer more stability and long-term sustainability.

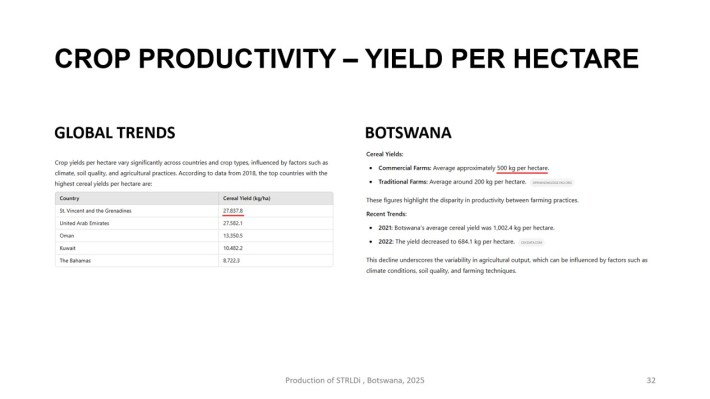

Resource-dependent emerging economies typically rely on their primary sectors for raw material production. They balance this dependency with a strong manufacturing base to drive economic growth. Botswana, with its central landlocked position, has the potential to become a regional hub for agriculture. It also has the potential for manufacturing. This creates much-needed employment opportunities.

Nonetheless, these sectors have struggled to develop (G&U). They contribute less than a tenth of what the retail sector generates. In some cases, they contribute as little as a fiftieth. As a result, job creation has lagged behind. The agriculture and manufacturing industries have yet to set up profitable business models. These models need to be scalable and sustain long-term economic growth.

For Botswana to fully realize its potential, these sectors must be restructured to guarantee they are both competitive and sustainable.

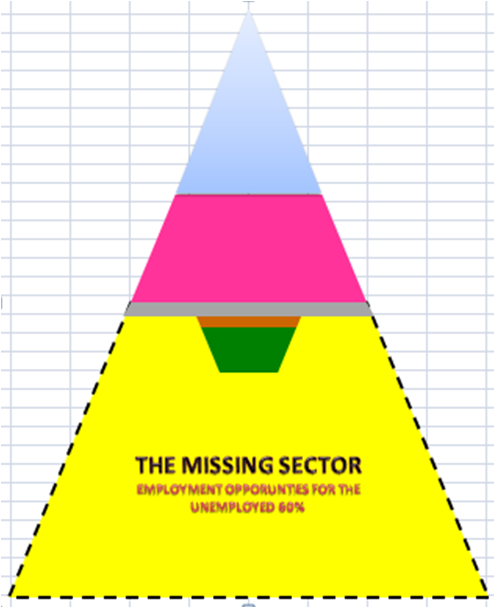

In contrast, extraction-based industries (diagram on the right) are typically technology-driven. They use fewer human resources and deplete the very foundation needed to build a resilient, job-creating economy.

(AS OF THE LAST CENSUS YEAR IN 2011) PRESENTED BY ECONOMIC SECTORS.

IT ALSO INCLUDES THE MISSING SECTORS.

IT SHOWS THE SCALE OF THE UNEMPLOYED WHEN THE FOUNDATION SECTORS ARE MISSING.

The grey, brown, and green portions represent the sizes of the manufacturing, mining, and agriculture sectors’ ability, respectively. These sectors should be readied to absorb unemployment.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Botswana

Progress through the study. Draw parallels between the three interlocking factors at play in your country. Discuss your observations. Reach a consensus on what these factors are. Determine how they are affecting your nation. Happy discovery!

These push the country’s inflation figures upwards. The value of the money erodes gradually, but its incline is definite (FtB). Both formal and informal retailers look for ways to raise income by raising their prices. They do this to support for the unemployed in their families. Couples take longer to get married and not as long to stay married (DG). Substance abuse issues tied to leanings towards over-promising and under-delivering at home and at work are part of the experience. An unstable personal life will also mean an unstable career life.

The reverse is also true.

🔗 LIKELY LEVELS OF UNEMPLOYMENT BY TYPES OF ECONOMIC SYSTEMS

Here is a breakdown of the likely levels of unemployment across the five major economic types. These are: Free Market, Planned Economy, Social Market Economy, Rentier Economy, and Tenderpreneurship. It also includes why unemployment tends to behave the way it does in each.

📊 Unemployment Patterns by Economic Type

| Economic System | Likely Unemployment Level | Key Characteristics & Causes |

|---|---|---|

| Free Market | 🔸 Moderate to High | Employment is based on supply and demand. Businesses hire based on profitability, not social need. During downturns, layoffs are swift. Structural and youth unemployment will be persistent. |

| Planned Economy | 🔹 Low (in theory) | Government assigns jobs to meet production quotas. Official unemployment is low, but underemployment and low productivity are common. The state often maintains artificial job security. |

| Social Market Economy | 🔸 Low to Moderate | The market drives job creation, but the state cushions shocks through public investment, social protection, and retraining. Unemployment is managed more strategically. |

| Rentier Economy | 🔸 High (especially youth) | Wealth from natural resources leads to a bloated public sector and neglect of productive sectors. Few private sector jobs. When rents decline, unemployment spikes dramatically. |

| Tenderpreneurship | 🔴 Very High & Unequal | Jobs are not created from productive growth but via elite networks and public tenders. Many skilled people stay unemployed while connected individuals cycle through contracts among themselves. |

🧠 WHY THESE PATTERNS MATTER

- In Free Markets, innovation and entrepreneurship may thrive—but only those with capital or skills benefit.

- Planned Economies prioritize full employment, but may create jobs that do not generate meaningful value.

- Social Market Economies manage the balance, cushioning the workforce while fostering economic growth.

- Rentier Economies offer short-term comfort but long-term fragility, especially for the unemployed majority without political or bureaucratic access.

- Tenderpreneurial Systems often produce elite employment bubbles, leaving youth and professionals sidelined from real economic participation.

Certainly! Here’s the revised and extended version with your new point seamlessly integrated, suitable for your WordPress blog post:

THE STRUCTURAL IMPACT OF EXISTING ECONOMIC MODEL CHOICES

Botswana’s early economic trajectory was shaped significantly by rentier and tenderpreneurial models. This fact is not lost on this study. These models have inherently limited the capacity for broad-based private sector job creation. By design, these models centralize economic opportunity around state-disbursed rents. They rely on politically influenced procurement. Rather than fostering diverse, innovation-driven enterprise ecosystems, they keep a narrow focus. As a result, higher unemployment levels are not just incidental but an expected outcome of such structural choices.

More critically, the long-term consequence is the erosion of the nation’s ability to develop basic economic solutions. These solutions are meant to support sustained, inclusive growth. There is an absence of robust investment in production-oriented sectors. This lack continues to hinder economic diversification and resilience. As a result, the country is left vulnerable to cyclical stagnation and socio-economic disenfranchisement.

Beyond these structural impacts lies an even deeper and more insidious effect. This effect is the shaping of mindsets across both the working-age and non-working population. Over time, the population has adapted to a prevailing belief system—a “silent societal order.” In this system, the current distribution of power and opportunity is viewed as unchangeable. This mental model conditions individuals to follow, rather than challenge, the framework for fear of exclusion or economic marginalization. As a result, generations internalize passivity and dependence. They see conformity as the only practical strategy for survival. They do not seek transformation through innovation, entrepreneurship, or civic engagement.

Introduction to Part 2

Click here for Part 2 of the article. It covers the next:

- Consideration of Socioeconomic Factors

- Pathways for Change and Empowerment